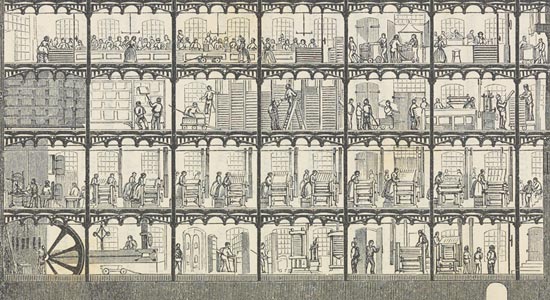

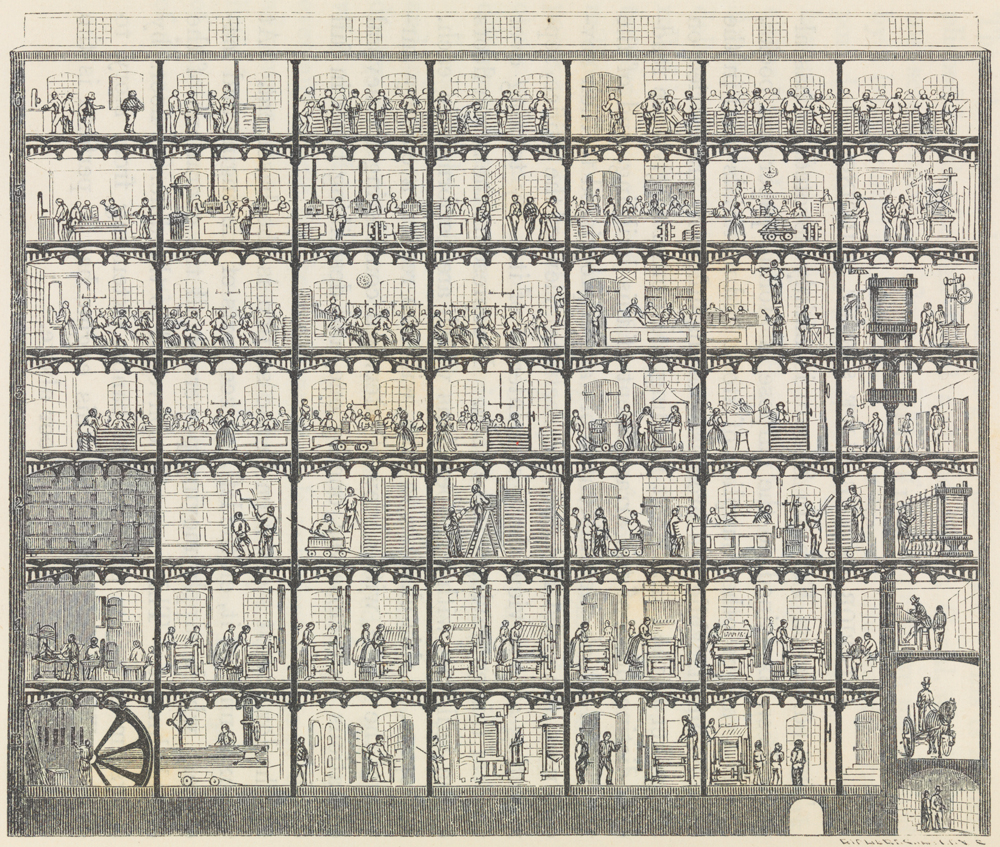

Carl Emil Doepler’s 1855 cross-sectional view of the Cliff Street building depicts schematically the activities that took place on each of the floors of the seven-story factory, which was connected by an iron walkway to Harper’s Pearl Street headquarters. Bogardus’s building, with its decorative and structural bowstring girders, frames every “room” of the image.

A mere fraction of the company’s enormous workforce can be seen in action here, albeit in a schematic fashion. Harper’s evidently took pride in promoting the factory, because this image was reused in a detailed article on periodical production in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in 1865. On the top floor, typesetters, or “compositors,” stand at their work stations with cases on the top story, composing text for the printing presses, including the “power-press,” also known as the “Adams” press after its inventor Isaac Adams, shown here. The various steam- and water-powered presses worked in the basement and on the first floor, all operated by an underground mechanical wheel, seen at the lower left of the image.

Carl Emil Doepler. “Sectional View of the Cliff Street Building” (Harper & Brothers Building), 1855. From Jacob Abbott, The Harper Establishment; or, How the Story Books Are Made (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1855). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Joseph B. Davis, 1942 (42.105.22).

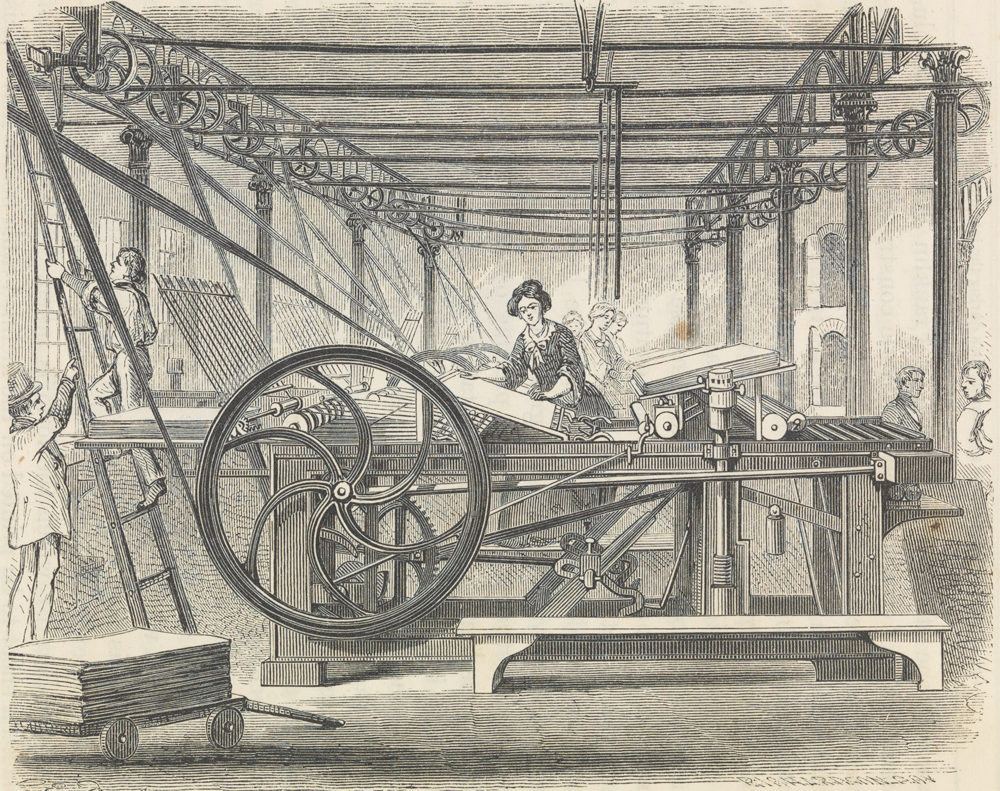

Harper & Brothers installed state-of-the-art technology in its new premises, including twenty-eight steam-powered presses. With a capable paper feeder, the machine could churn out 6,000 sheets a day, each containing sixteen pages. A worker sat at an “Adams” press, feeding paper into the apparatus, which then printed each sheet and mechanically re-inked the rollers. In this illustration, the machine overwhelms the room but is well integrated into the structure of the building itself.

Paper feeding was one of the jobs given to low-paid women, along with folding, book burnishing, and gilding, similar to the system in Edward Anthony’s stereoview factory. Publishers such as Harpers employed fewer skilled printers but opted for more low-paid laborers, taking advantage of large-scale factory production and technological innovations such as the “Adams” press. Women and young boys, several hundred of whom made up the firm’s workforce, earned about five dollars a week.

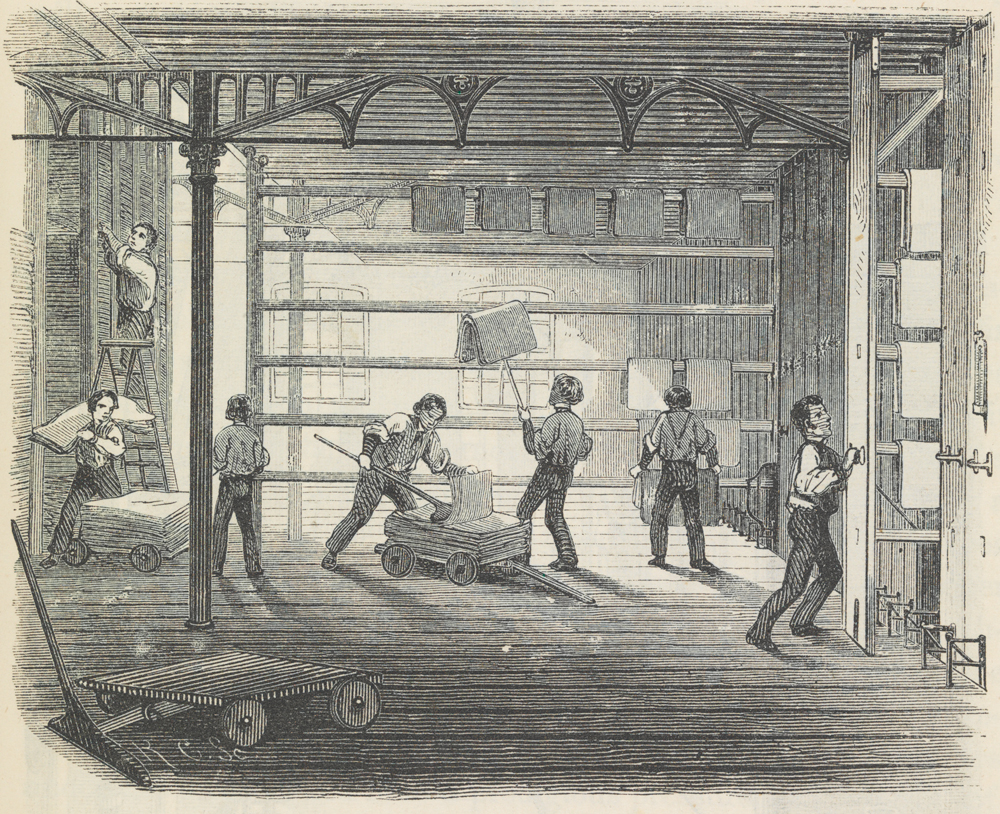

Because paper must be wetted for printing, the printed sheets were brought upstairs to be manually hung up to dry and were later pressed, folded, sewn, and bound. As shown here, enormous racks would be rolled in and out and filled in order to conserve space. The second floor of the Cliff Street factory contained twenty-five drying racks, each holding up to two thousand sheets. Fifty thousand sheets could be dried every three hours before being moved to the hydraulic presses nearby for pressing and folding.

Carl Emil Doepler. “The Drying Room,” 1855. From Jacob Abbott, The Harper Establishment; or, How the Story Books Are Made (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1855). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Joseph B. Davis, 1942 (42.105.22).

This image shows the entire sixth floor of the Cliff Street building. After drying and pressing, women would fold the sheets with a paper-folding machine (introduced in about 1865), which could fold up to 14,000 sheets daily; before then, the sheets were folded by hand. The sheets were then machine sewn, and in the case of a book, the covers were sized, cut, and applied and fly leaves were pasted down by hand. Finished books and periodicals were carried to the Pearl Street building for storage and distribution.