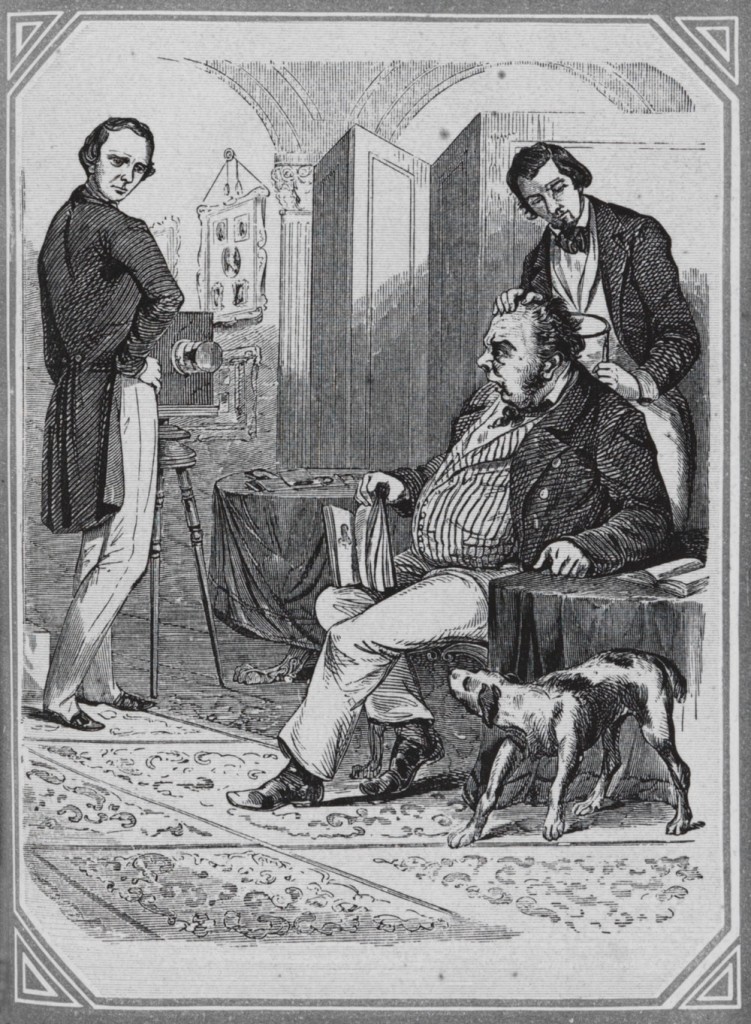

Daguerreotypes required long exposures, which challenged a sitter’s ability to hold still, so a vise was sometimes used to immobilize the head. Although the vise might have made sitters feel awkward, as seen in the satirical illustration, Brady’s charm and charisma helped sitters at his studio look confident and at ease for the camera.

In this image, the sitter and operator have overcome the discomfort of the vise to achieve a natural, graceful likeness. Women rarely worked the cameras at professional studios but instead labored in back workrooms, hidden from the public.

Woman Daguerreotypist with Camera and Sitter, ca. 1855. Sixth-plate ambrotype. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 2005.27.5. © Nelson Gallery Foundation. Photo: Thomas Palmer.

Men called operators (borrowed from textile factory “operatives”) worked the cameras and enjoyed higher pay than most gallery staff. At Brady’s studio, operator Luther Boswell took this daguerreotype of the celebrity vocalist Jenny Lind and received complimentary concert tickets from “the Swedish Nightingale” after the portrait session concluded. Brady focused on posing sitters and publicizing the studio rather than working behind the camera, but he was the one who received artistic credit for the studio’s portraits.

Mathew Brady, operated by Luther Boswell. Jenny Lind, 1852. Sixth-plate daguerreotype. Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA, purchase, partial gift of Kathryn K. Porter and Charles and Judy Hudson, 89.75.

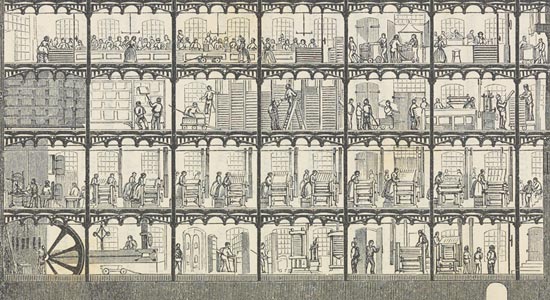

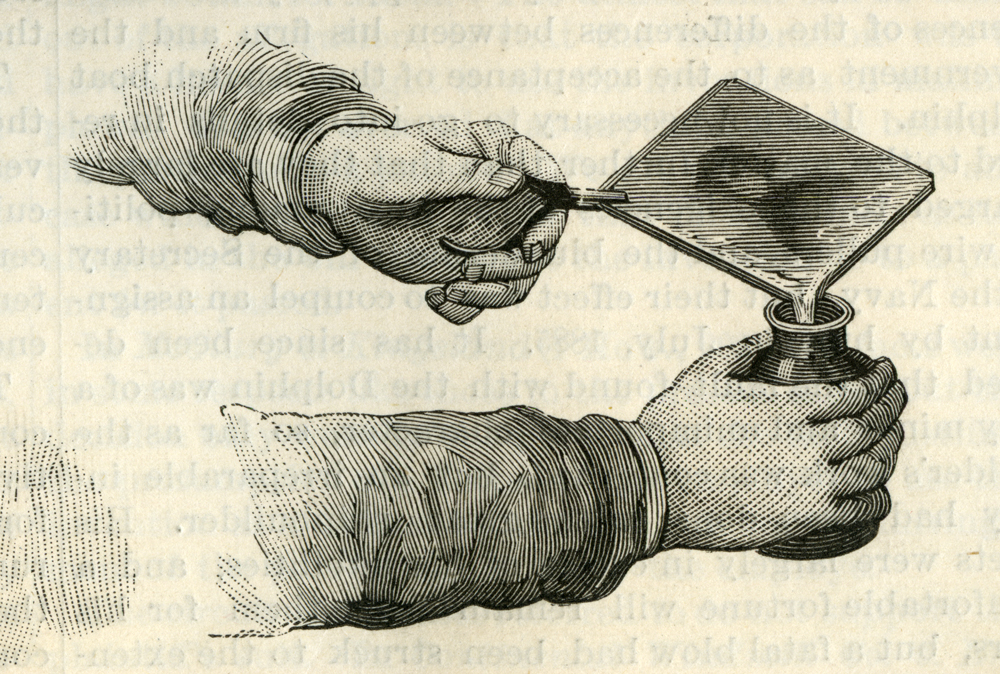

Immediately before the exposure, a worker in a back workroom would apply iodine vapors to sensitize the silver-coated photographic plate to light. The worker would then deliver the plate to the operator, who would take the photograph. The daguerreotype process did not involve negatives, and thus daguerreotype images were unique products.

After the operator took the daguerreotype, the photographic plate would return to the workrooms, where workers would apply mercury vapors to develop the photograph and use other chemicals to fix the image. Others would then apply color to the daguerreotype by hand. Finally, the delicate photographic plate would be encased behind glass. In New York in 1850, of 127 total daguerreotype studio staff, 46 were boys and 11 were women.

George M. Hopkins. “Reminiscences of Daguerreotypy,” Scientific American, January 22, 1887. The Daguerreian Society.