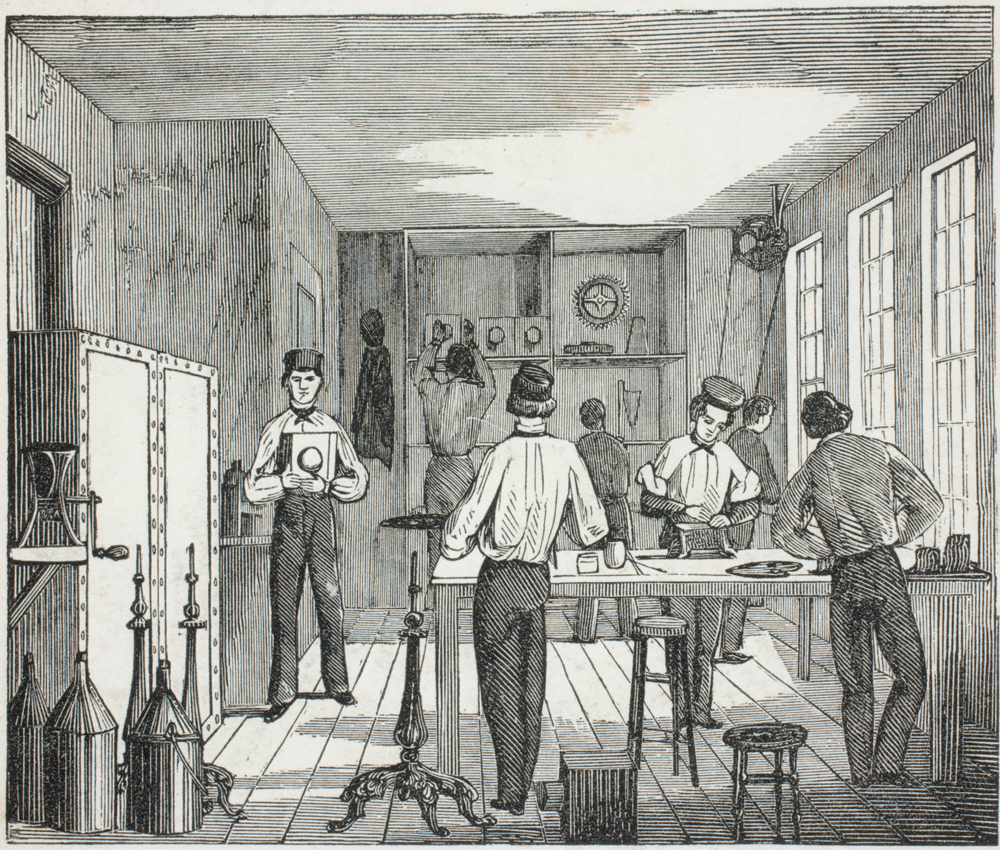

The inside of Anthonys’ Stereoscopic Emporium at 501 Broadway attracted attention for its architectural ornamentation and its bold signage and likely resembled the retail space of their competitor D. Appleton & Co., illustrated in this stereoview. Products manufactured by the Anthonys were sold in the store or shipped to mail-order customers along with their imported goods. Thousands of stereocards and a diverse selection of hand-held and standing stereoscope models were featured in the advertisements and catalogue offerings, as well as in the emporium.

D. Appleton & Co. Interior view of the D. Appleton & Co. Stereoscopic Emporium, 346 and 348 Broadway, New York. Dealer in every kind of Stereoscopic Views & Instruments, Domestic & Imported, ca. 1860. Hand-colored albumen prints from glass negatives (stereoscopic views). The Jeffrey Kraus Collection, www.antiquephotographics.com.

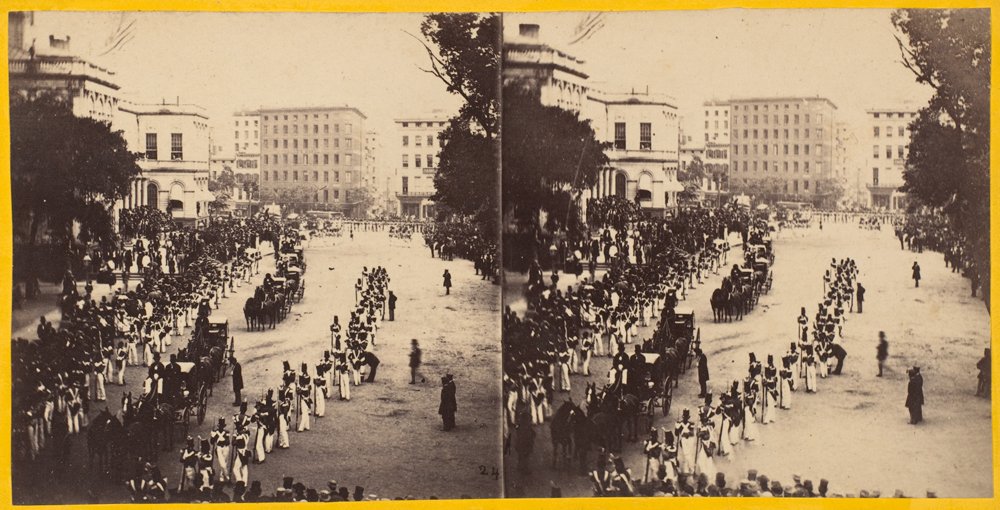

The Anthony Company relied on its own photographers as well as commissioned professionals to supply its immense catalogue of stereographic images of places around the world. As a result, the stereoview subjects ranged from local New York street scenes to exotic tourist attractions abroad and documented major national and international events, such as the visit of the Japanese diplomatic trade delegation to New York in 1860. Many of the twenty-four images in the series were taken from windows overlooking the procession along Broadway, a common practice if one was to obtain the best perspective and composition.

Edward Anthony and Henry T. Anthony. Return of the Japanese Embassy from City Hall, 1860. Albumen silver prints from glass negatives (stereoscopic views). Instantaneous View, No. 24, published by E. & H. T. Anthony & Company. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Herbert Mitchell Collection, 2007 (2007.457.3626).

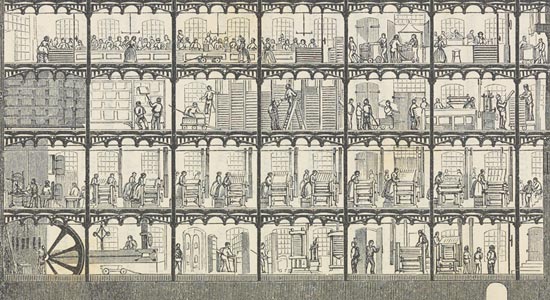

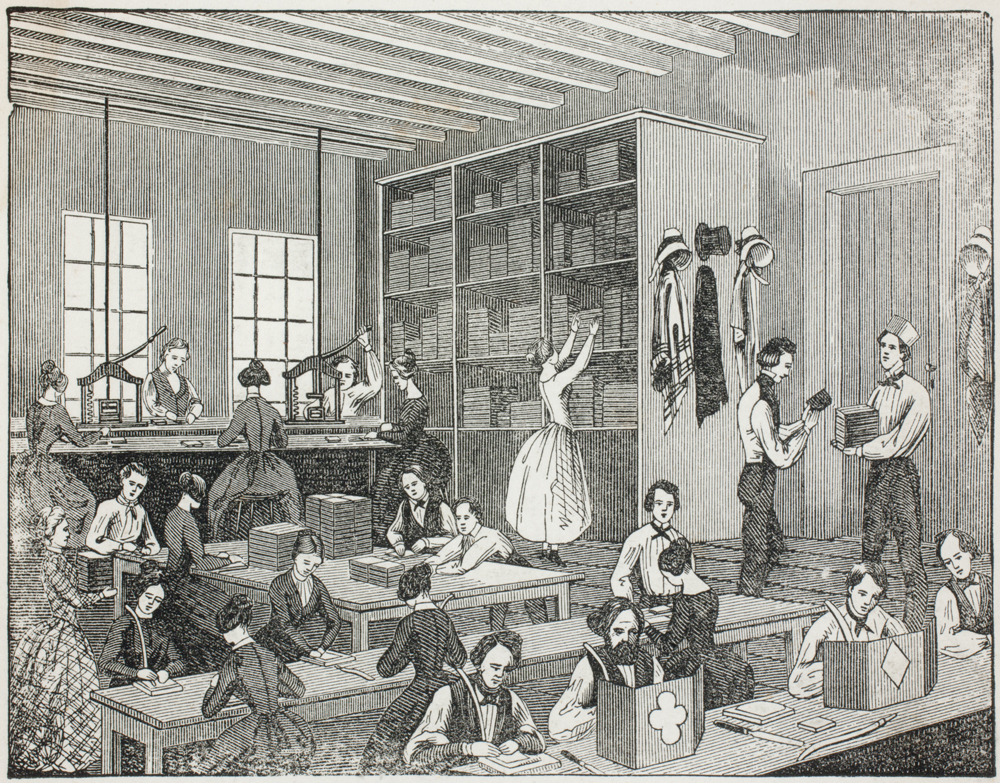

The Anthony firm’s numerous rooms contained specialized functions, similar to those in the Harper Brothers’ building. Some items, such as camera equipment, photographic chemicals, stereoviews, and stereoscopes, required multiple steps and passed through the hands of many employees in different departments. Snelling’s chemical expertise helped him to develop photographic paper that had increased sensitivity and a finishing gloss, which produced an attractive, shiny appearance, along with rapid shutter technology that made the Anthonys’ “Instantaneous Views” possible. This image shows men completing the final stages of camera construction; the women mainly staffed the paper-production line, dipping pages into egg albumen, fuming them, and hanging them to dry.

“Finishing Room.” From Henry Hunt Snelling and Edward Anthony, A dictionary of the photographic art . . . together with a list of articles of every description employed in its practice (New York: H. H. Snelling, 1854). George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film.

Photographs were typically printed from glass collodion negatives on albumen paper. This work occurred in a building separated from other production areas, in an environment with reduced dust and increased natural light. After the printing was complete, the process of creating a stereocard typically involved more than fifty employees, most of them women. They selected the pictures, cropped them to an identical size, and mounted the images and labels on card stock. The final step, in which glossy finishing was applied, required the most physical labor and was often performed by male workers.

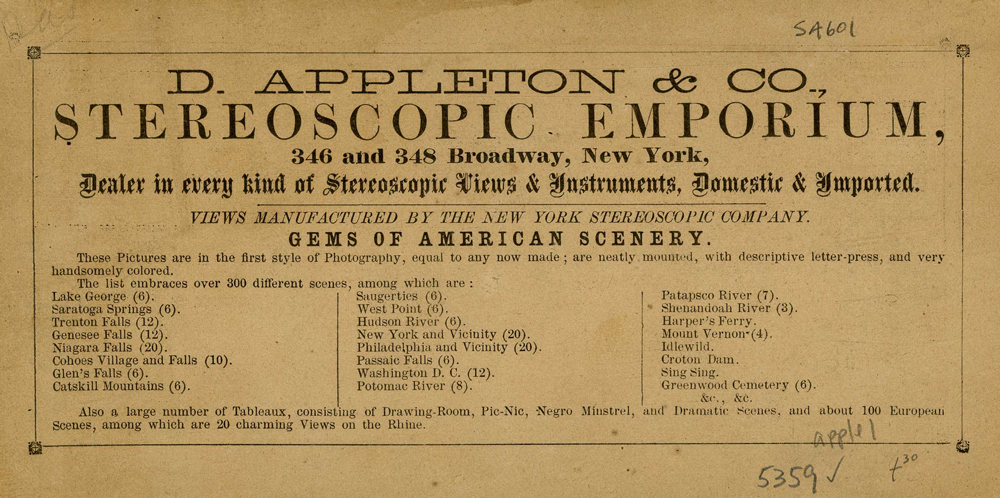

Reverse of D. Appleton & Co. Interior view of the D. Appleton & Co. Stereoscopic Emporium, 346 and 348 Broadway, New York. Dealer in every kind of Stereoscopic Views & Instruments, Domestic & Imported, ca. 1860. Albumen prints from glass negatives (stereoscopic views). The Jeffrey Kraus Collection, www.antiquephotographics.com.