Fig. 1 Broadway from Chambers St., looking north, ca. 1850. Lithograph. Eno Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

On September 26, 1846, an advertisement in the New York Herald touted a new space for “Fashionable Shopping in New York,” Irish entrepreneur A. T. Stewart’s freshly completed dry goods emporium at 280 Broadway. Built on the “unfashionable” east side of Broadway, Stewart’s Italianate “Marble Palace” became a household name and landmark within just four years, frequently cited in ladies’ journals and newspapers. In an 1850 lithograph depicting Broadway from Chambers Street (fig. 1), the Marble Palace dominates the streetscape in its scale, yet its incorporation into the surrounding urban scene does little to convey Stewart’s enormous impact on the experience of retail shopping in New York.

Stewart’s innovation was not limited to the store’s Tuckahoe marble façade studded with plate glass. By rethinking the interior organization of his store, Stewart changed how people shopped. Merchants of the early nineteenth century brought order to the jumble of products offered by their predecessors by compartmentalizing their displays and providing a welcome respite from the chaos of the city street. Stewart applied this rational system to the retailing of fancy dry goods, thus generating an early version of the modern department store. Stewart’s emporium synecdochically represented a gridded and increasingly segmented New York, and early commentary from Godey’s Lady’s Book notes new departments and displays at Stewart’s, indicating awareness of the store’s transformation of the shopping experience in the modern city. Nineteenth-century consumers would have been most struck by Stewart’s use of multiple floors for retail display. Retail space had formerly been limited to street level, with the upper floors reserved for wholesaling and often living quarters for merchants.

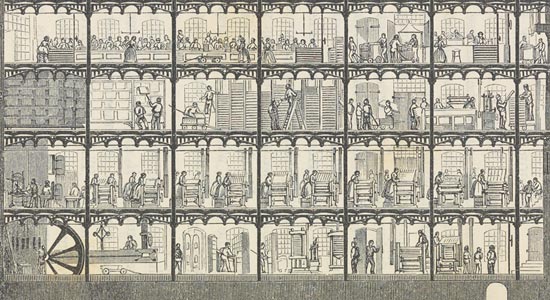

Fig. 2 Charles Parsons. An Interior View of the Crystal Palace, 1853. Chromolithograph, printed by Endicott & Co., published by George S. Appleton. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Edward W. C. Arnold Collection of New York Prints, Maps and Pictures, Bequest of Edward W. C. Arnold, 1954 (54.90.1047).

+Beginning in 1853, Stewart’s compartmentalized Marble Palace gained a counterpart in the New York Crystal Palace at Forty-second Street. Built in response to London’s Great Exhibition of 1851, the New York Crystal Palace housed the first world’s fair in the United States. Optimistic press publicity did not result in commercial success, but numerous commemorative representations of the glass and cast-iron exhibition pavilion glorified the building’s exterior. Charles Parsons’s lithograph for George S. Appleton (fig. 2) provides a rare interior view, capturing a series of rationally organized departments and the grand scale that mirrors descriptions of Stewart’s interior layout. Although both buildings featured spectacular yet ordered displays of goods, the connection eluded the press of the time. Nevertheless, Stewart’s customers must have drawn a visual analogy between the two, for few would have ever seen a grand structure of such material abundance, especially those without firsthand knowledge of European world’s fairs. Both structures were claimed as emblems of American achievement, and both were referred to as palaces designed to foster consumption. Stores such as Stewart’s afforded female consumers an outlet for socialization and self-determination outside the home, albeit one that revolved around the conspicuous consumption of fancy goods.

Stewart’s establishment of an all-retail store uptown in 1863 further feminized shopping. The new “Iron Palace” at Broadway between Ninth and Tenth Streets was a retail destination for women’s consumption, whereas the Marble Palace had combined wholesale and retail sales. A. T. Stewart’s uptown expansion prefigured the development of a specialized “Ladies’ Mile” of various emporiums offering both fabrics and ready-to-wear clothing, such as Lord & Taylor, Beck’s, and Arnold Constable & Co. Not unlike the New York Crystal Palace with its “Ladies’ saloon,” these stores offered various comforts and conveniences in order to entice female shoppers to linger, from the Iron Palace’s first-floor counter for customers to write out notes and orders to Macy’s soda fountain, established in 1870. This equation of shopping with other forms of commercialized leisure would become even more pronounced toward the end of the century with the incorporation of ladies’ lunchrooms into ever-expanding palaces of consumption.

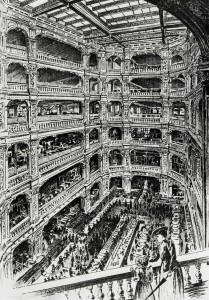

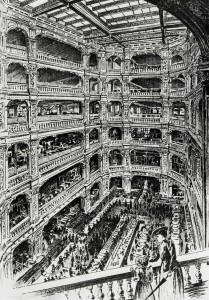

Fig. 3 Interior of A. T. Stewart’s Astor Place Store, ca. 1880s. Engraving. Collection of The New-York Historical Society, Bella C. Landauer Collection.

+Lord & Taylor and Macy’s pioneered the use of extensive window displays to attract customers from the street, yet Stewart’s continued to focus attention on the store interior. The Iron Palace employed modern plate glass and cast-iron construction more for the sake of letting natural light into the store than for the benefit of passing window shoppers. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper even noted that Stewart’s needed no identifying sign on its façade, indicating its fame as a New York landmark, particularly among the upper-class ladies Stewart targeted as customers. In early 1863, Alice B. Haven provided Godey’s readers with a tour of the Iron Palace’s interior, orienting new visitors bewildered by the store’s multiple levels and departments. Her basement-up outline is systematic overall, yet she pauses at several points to romanticize the novelty of the scene before her. Between the first and second floor she notes:

On the landing, half way up, we pause for a coup d’oeil of the busy sparkling scene below. Now we have a full view of the saloon itself; the light and tasteful frescoes on wall and ceiling; the gilded chandeliers with grand glass globes; the graceful Corinthian columns, all of iron, that surround the floor above; the innumerable plate-glass windows, with the pale blue tint pervading the light that painters seek to soften an atmosphere, or tone down color; the gayly [sic] dressed, restless, ever-changing throng, like a waving tulip-bed, or the glittering of a kaleidoscope, with an ascending hum that marks a hive of human activity and industry.

This sensational description of the bustling interior finds a visual equivalent in a later panoramic image of the uptown store from two decades later (fig. 3), in which a fashionable mother and daughter peer over one of the gallery balconies to survey the scene below. Though artificially frozen in time, this sketch attempts to illustrate the “throng” of customers crowding around the various first-floor counters, while also showing the departments around and above yet to be explored. Both the galleries and the sunlit glass ceiling in this image recall Parsons’s interior of the New York Crystal Palace, and Haven’s narrative makes special note of her view from the topmost gallery. The store’s sheer height would have been a marvel to nineteenth-century eyes, and Haven’s breathless description parallels the immense popularity of bird’s-eye and steeple views of New York City during this period. While prefiguring later guidebook-style articles on Stewart’s, Haven provides the most personal, woman-to-woman perspective on the experience of shopping at the Iron Palace.

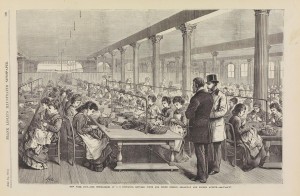

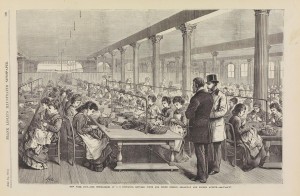

Fig. 4 “The Sewing Room at A.T. Stewart’s.” From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, April 24, 1875. Collection of David Jaffee. Photographer: Bruce White.

+Haven also asks to go behind the scenes, actively seeking out the female employees in the “great work rooms we hear exist above us, yet so silent and secluded in their operations that not one in ten of the ‘oldest customers’ guesses their existence.” Feminist solidarity may partially account for Haven’s curiosity, yet her portrait of the spacious, well-ventilated workrooms where Stewart’s ready-made goods are produced seems to anticipate criticism of the industry’s exploitation of cheap labor. Frank Leslie’s illustration of Stewart’s immaculate, orderly sewing room from 1874 (fig. 4) similarly aims to reassure urban consumers, who gradually became uncomfortable with the invisible sources of their ready-made clothing.

Stewart’s increasingly resorted to spectacle to compete with other dry goods palaces that were cropping up along Broadway. Publicity stunts such as the annual spring “exposition” began in 1871. Contemporary accounts describe the store’s rotunda draped with all manner of luxurious fabrics, and several draw a parallel between Stewart’s display and the recent Exposition Universelle in Paris. Such comparisons lent fashionable cachet to Stewart’s offerings of imported goods. Nevertheless, the press was eager to contextualize Stewart’s dazzling displays as a distinctly American variant of the “brilliant and varied exhibition of the industry and taste of all nations.”

The Iron Palace survived several years after Stewart’s death, but ultimately the store’s competitors overwhelmed the once eminent New York institution. A. T. Stewart had revolutionized shopping in nineteenth-century New York, defining the consumption of fabrics and fashion as a feminine practice situated in a dedicated district of Broadway. Stewart and his successors stimulated demand for products through their carefully ordered displays and departments, which developed hand in hand with world’s fairs and expositions in the United States and Europe. Department stores developed in earnest in the 1890s, but Stewart’s and contemporaneous palaces of consumption provided forerunners of the form. By looking at the nineteenth-century shopping experience, we can reconstruct the significant role consumption played in the modernization of New York.