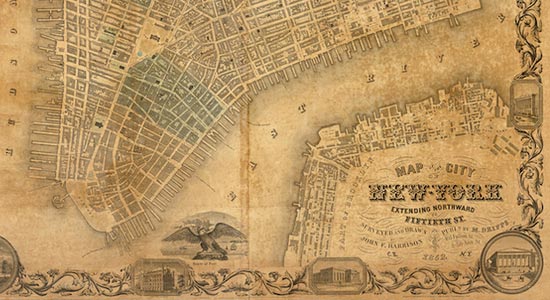

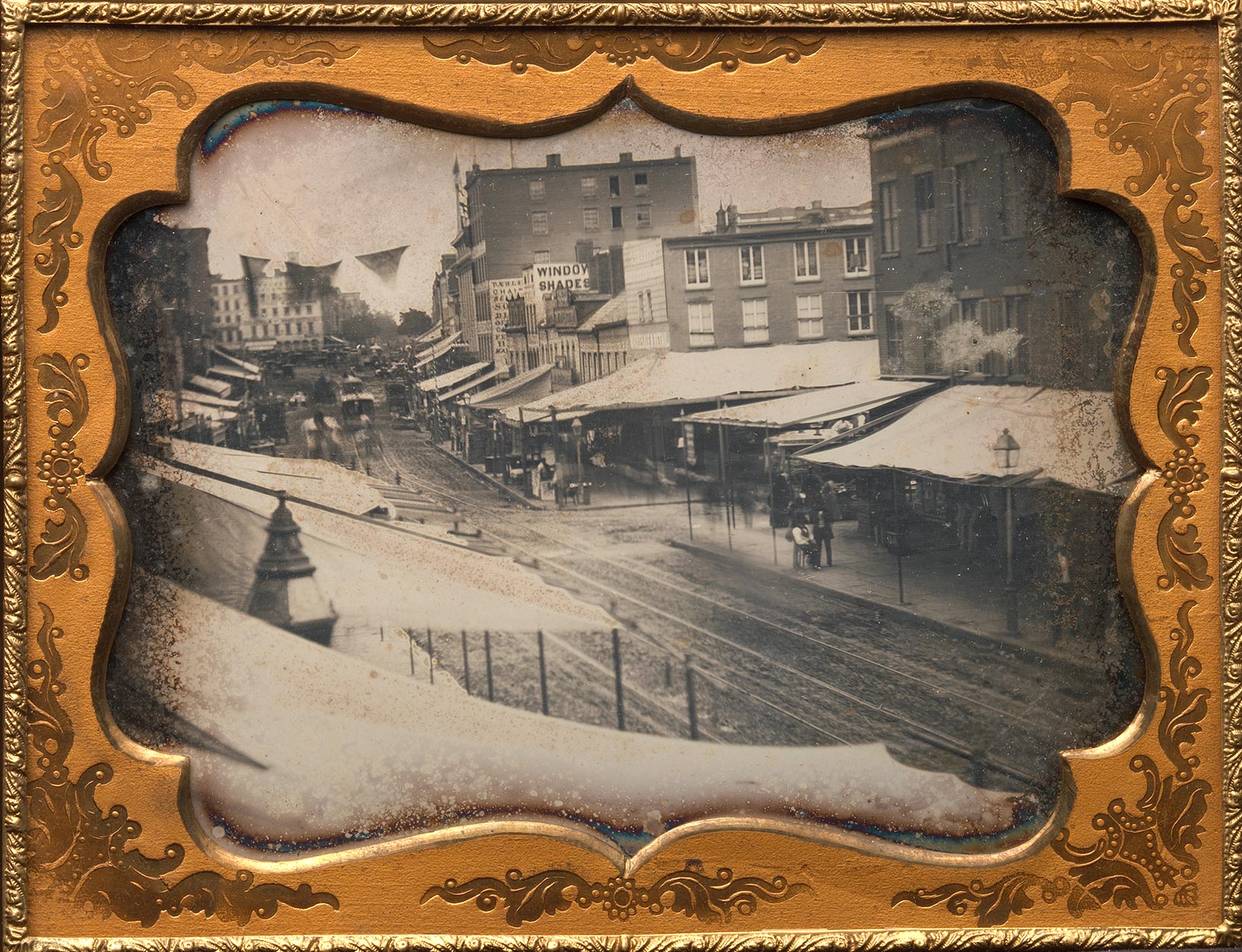

The daguerreotype entitled Chatham Square, New York (fig. 1) of about 1853, captures a rare street scene of the busy downtown area that was known for its cheap shopping, entertainment, and daguerreotype studio-factories, which existed in stark contrast to the more elite Broadway establishments. Daguerreotypes represent an early phase of photography whose development was hailed for its scientific and technological progress, but entrepreneurs quickly seized on the new art form for its commercial possibilities as a medium for portraiture, and nowhere more so than in New York City. Prices dropped over the course of the 1840s and 1850s, replacing the miniature portrait for some and offering affordable portraits for all. The Chatham Square daguerreotype is therefore unusual because of its subject: a street scene.

The Chatham daguerreotype captures antebellum New York, even if its quotidian view of crowds and carriages begins to blur at a distance. An amateur most likely took the image, possibly from the second story of a building that housed one of Chatham’s competitive daguerreotype studios. The Chatham Square Post Office and Purdy’s National Theatre are featured alongside other nineteenth-century structures. Railroad tracks and commercial signage indicate the industrial nature of the neighborhood, built at one of the city’s oldest intersections, a former Indian trail.

Another early rare New York street scene of about the same date, possibly of Greenpoint, Brooklyn, is also unusual for its whole-plate daguerreotype size (fig. 2). Like the Chatham image and most of the other surviving daguerreotypes, the artist remains anonymous. He or she most likely traveled to the site from a Brooklyn studio, although there were also itinerant daguerreotypists who made decent incomes by traveling far from home with their gear in tow and photographing homesteads in rural areas. One 1840s peddler daguerreotypist, for example, recorded earnings of $100 per day!

What makes this Brooklyn scene significant is the mirror-like reflection of its subjects, which represents a romantic interest in nature. The sun approaches from the left side of this treeless landscape, indicating a skilled artist who understood the crucial role of lighting in daguerreotype making. The three-story building at the center has red and green plants and planters, applied with hand-coloring, a technique practiced by 1842. Traditional daguerreotype frames like this one had glass covers that matched the plate’s size and secured it in its frame. Frame covers were made of leather, as in this case, or of plastic after 1855, and they were commonly lined with velvet. In fact, some daguerreotypes were melted down or stripped for their precious materials, including silver and leather, and therefore do not survive.

Landscape daguerreotypes were far less common than portraits, although still popular during this period. The reflections in the daguerreotypes promoted the wonders of nature and contrasted the fictional capabilities of paintings, which aligned with the period interest in photographic realism. Street scenes of the 1840s and 1850s survive from several American cities, including Philadelphia, Boston, New Orleans, St. Louis, and San Francisco, although early scenes of New York are extremely rare, highlighting the significance of these images. Daguerreotypists sometimes took these street photos from indoors, peering out second-story windows to capture broad views of landmarks or events, as was the case with the Chatham daguerreotype. Other daguerreotypists might set up their gear outdoors to capture urban scenes, like the arrival of a circus, or natural wonders like Niagara Falls, but this genre is even rarer because the daguerreotype equipment and process were cumbersome and not easily worked with outside the studio. Additionally, weather and lighting impacted this delicate process, making outdoor work even more hazardous.

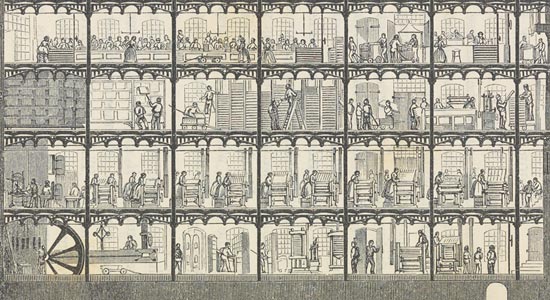

The daguerreotype image was produced on a thin sheet of silver-coated copper that went through five stages: first it was polished and buffed; then it was prepared in iodine vapor; afterwards it was placed in a camera obscura and exposed to light; it was then placed in hot mercury to reveal the image; and finally it was gilded. Chemicals were used throughout these stages, and many daguerreotypists struggled with their health because of these exposures. Still, daguerreotypists took pride in developing their own chemical recipes and closely guarded their powders and solutions, which were crucial elements to the success and sophistication of their products.

Although daguerreotyping required significant expertise and specialized equipment, many mechanics or artisans entered the trade with little knowledge of art or technology, seeking additional income and still producing decent portraits. In 1902 James F. Ryder noted, “It was no uncommon thing to find watch repairers, dentists, and other styles of business folk to carry on daguerreotypy ‘on the side’! I have known blacksmiths and cobblers to double up with it, so it was possible to have a horse shod, your boots tapped, a tooth pulled, or a likeness taken by the same man; verily a man—a daguerreotype man—in his time, played many parts.”

Cheap daguerreotype shops and factories, like the ones described in Ryder’s text, were opened in the Chatham area, where the working classes went to memorialize their families and occupations. Because of the proliferation of this mechanical innovation, the increase in demand, and the fierce business competition, daguerreotype prices decreased to as low as twenty-five cents, though presumably for very small portraits, like sixteenth-plates (1 3/8 by 1 5/8 inches). Mathew Brady, the prominent Broadway daguerreotypist, campaigned against cheap daguerreotype factories and their “Cheap John” practitioners to protect his own artistic stature as displayed in his upscale Broadway studio (See McRee, Mathew Brady and the Daguerreotype Portrait). In the Chatham shops, visitors received much less personal attention than on Broadway, with scripted paths that hurried them through visits and dictated that they enter and leave through different doors. In an 1890 publication, John Werge recorded his visit to a cheap daguerreotype factory on Broadway, which competed with Chatham’s daguerreotype shops: “Having had my number of ‘sittings,’ I was requested to leave the operating room by another door which opened into a passage that led me to the ‘delivery desk,’ where, in a few minutes, I got all my four portraits fitted up in ‘matt, glass, and preserver,’—the pictures having been passed from the developing room to the ‘gilding room,’ thence to the ‘fitting room’ and the ‘delivery desk,’ where I received them. Three of the four portraits were as fine Daguerreotypes as could be produced anywhere.”

Chatham Square also rivaled Broadway for its popularity as a visual spectacle—but one of a different kind. The Chatham area was mainly associated with popular culture and the working classes, who were drawn by the street fairs and saloons located throughout the square and the neighboring Bowery. Sometimes members of the upper-class would come to observe the fashion and behavior of the “others.” Iconic New York characters, such as the Bowery B’hoys and G’hals, made these neighborhoods their home and promenaded in their brightly colored clothing, challenging the era’s expectations of public decorum.

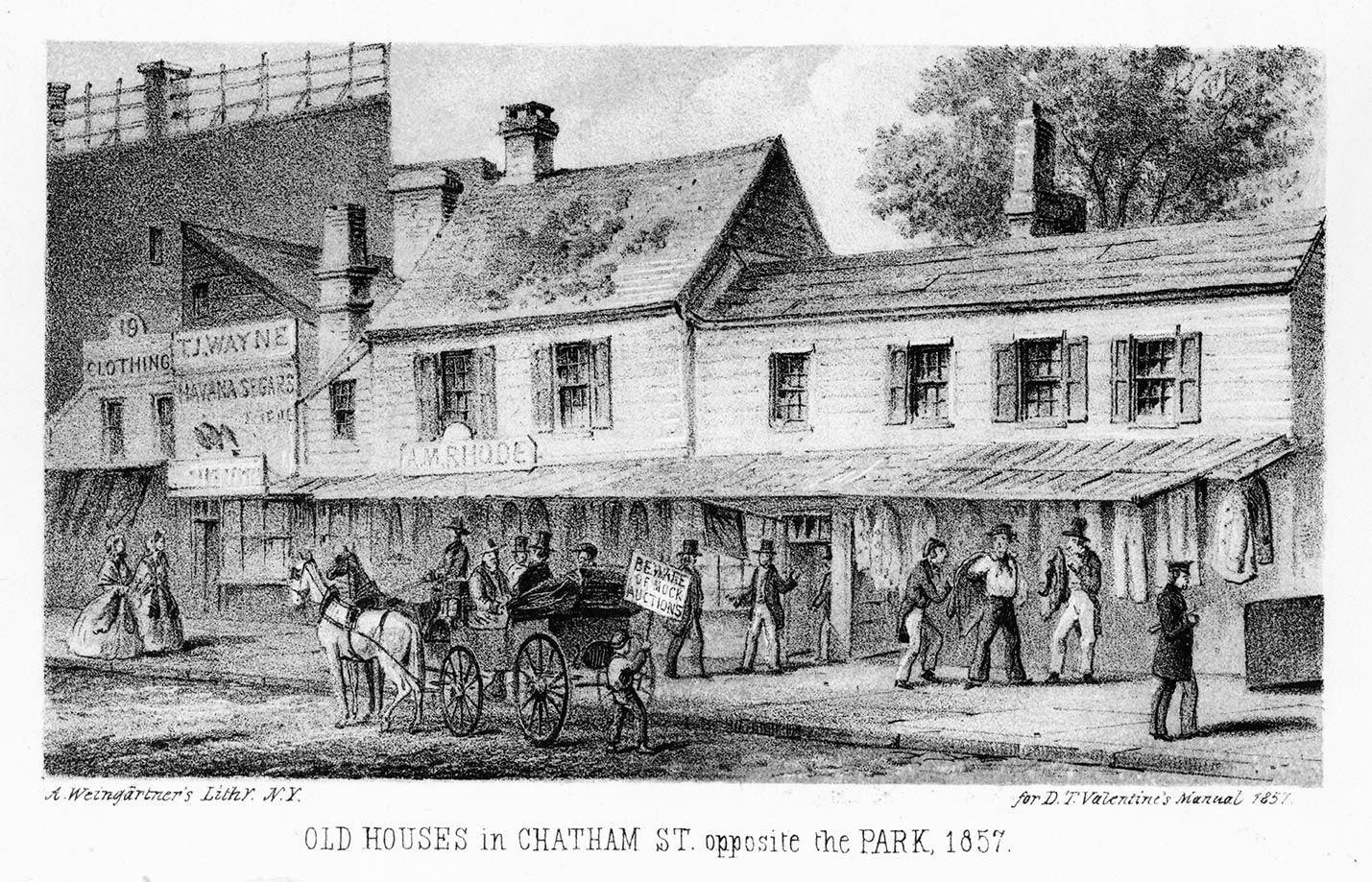

The lithograph Old Houses in Chatham St. Opposite the Park, 1857 (fig. 3), by A. Weingärtner Lithography, upholds the characterizations of the Chatham area. This image was published in P. T. Valentine’s Manual of the City of New York of 1857 (opposite page 548), a serial publication (1841–70), to illustrate the anomalous old houses on Chatham Street that stood apart from other nearby, newer structures. Chatham Street is described in the manual as one of the city’s most popular thoroughfares, despite the dilapidated condition of the houses. The “Clothing” sign on the rundown house marked “19” highlights the conditions of cheap Chatham stores. The moving figures that wear plain dress are likely on their way to work or shop. At the center, a horse and carriage pass by, and alongside them a youth presents a sign that reads “Beware of Mock Auctions.” These signs were mandated by the mayor because of the area’s dishonest merchants, who swindled buyers and harmed the reputations of Chatham’s and Bowery’s “Cheap Johns,” who were famous for their low-cost merchandise.

Chatham’s mock auctions were famous, appearing often in period artwork and texts such as the 1843 painting Auction in Chatham Square by E. Didier (fig. 4). Open-air auctions, however, no longer took place by the time this painting was made; auction permits were no longer made available after 1820 because of complaints from nearby shopkeepers. In this busy scene, a woman pulls on the overcoat of the auctioneer, representing the crowd’s lack of social etiquette. The purchase of second-hand furniture, as depicted in the painting’s auction, was common practice in New York at this time, although mock auction shops, which mislabeled their merchandise and dishonestly drove up their prices, were to be avoided.

The South Carolinian William Bobo encapsulates the mixture of delight and concern experienced by visitors when approaching the enchanting Chatham area: “I am always in a hurry when I go through this street; I am afraid of being run over, or having my pockets picked. Chatham-street is like a museum or an old curiosity shop, and I think Barnum would do well to buy the whole concern, men, women, and goods and all out, and have it in his world of curiosities on the corner of Ann and Broadway. I think it would pay finely.”

Chatham Square and its robust industry were captivating to visit and document, because it was reliably interesting for both its honest and its dishonest prospects. Visitors and readers alike were curious about Chatham Square and its role in the city’s growing commercialism and material consumption. In fact, the topics of cheap manufacture and shopping were popularly discussed and presented in periodicals and exhibitions of the time. Chatham’s competitive daguerreotype and clothing production contributed to the accessibility and proliferation of affordable materials to more people. The visual display of Chatham’s establishments drew large crowds who were united by these common interests.