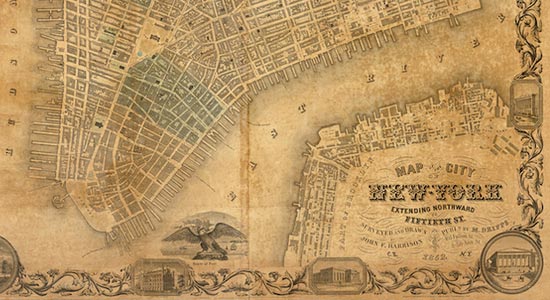

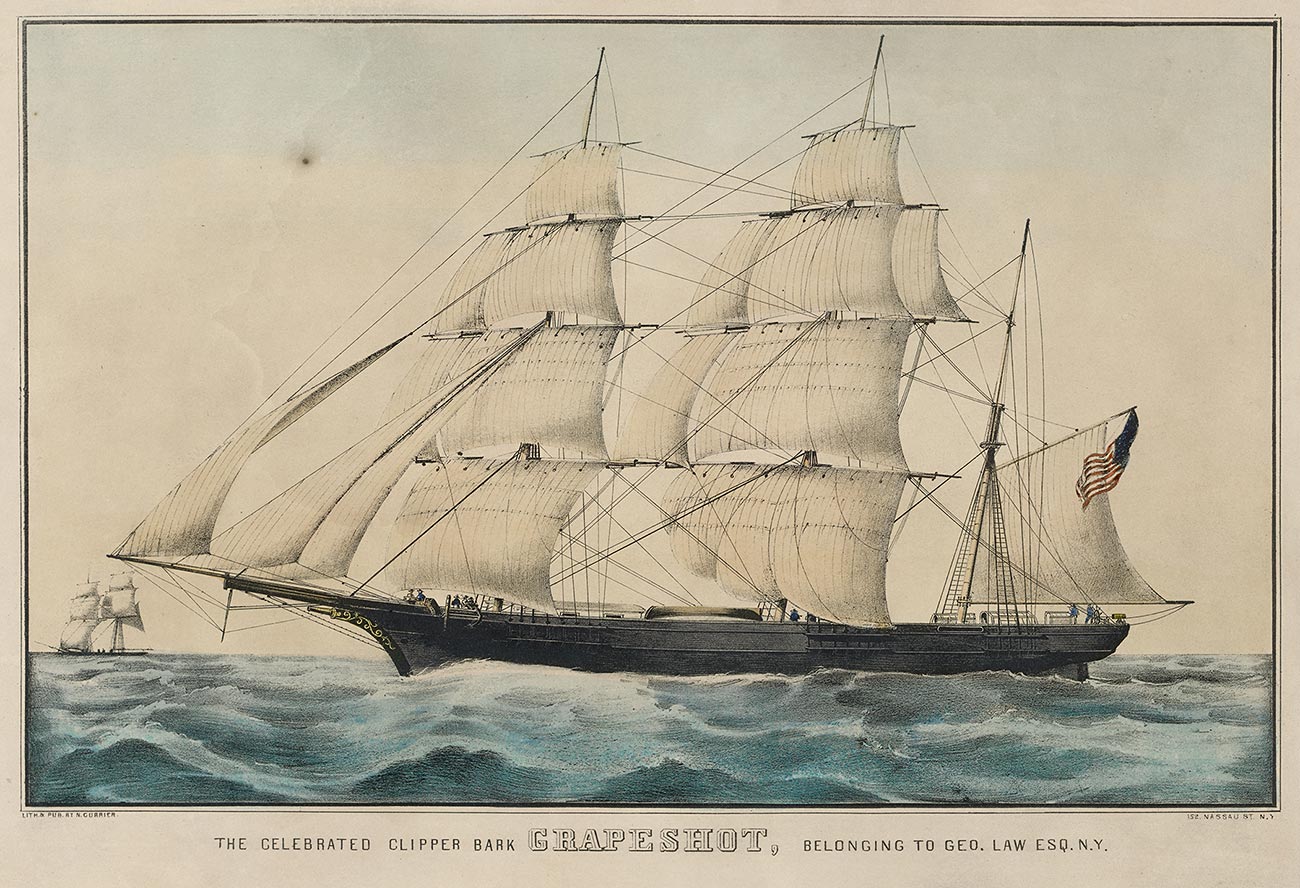

Although it is difficult to summarize the diverse output of the firm founded by Nathaniel Currier and James Merritt Ives as New York’s eminent “printmakers to the people,” this extant lithograph stone (fig. 1) offers insights into the complex process of manufacturing and marketing of each Currier & Ives print. Most of the firm’s equipment was liquidated when Currier & Ives closed in 1907, but fortunately a few stones, such as this one depicting a well-known clipper ship, survive to this day. By tracing the biography of a print pulled from this stone, I aim to provide a brief portrait of the production and consumption of Currier & Ives’s extensive stock of printed images.

Made from Bavarian limestone, this stone would have been prepared in one of Currier & Ives’s factory buildings. The firm occupied 2 Spruce Street from 1838 to 1865, but 33 Spruce became the firm’s manufacturing headquarters from 1866 on. According to Harry Peters’s 1929 history of the firm, Currier & Ives dedicated the fourth floor of 33 Spruce Street to the first stages of their print production process, providing an open workspace for collaboration between artists, lithographers, and printers. Some of the firm’s contract artists, such as Louis Maurer, drew their designs directly on prepared slabs of limestone, using the greasy lithographic crayons manufactured by Nathaniel Currier’s cousin Charles. Other artists, however, merely provided sketches to be transferred on to stone by one of the firm’s dedicated lithographers. Because lithography transposes a mirror image to the final paper, each design would have to be worked in reverse, and a specialized letterer would draw any identifying text, like the caption seen on this stone. The absence of a signature on the stone is not unusual, although given its subject matter, the design may have been the work of Charles Parsons, another artist frequently employed by Currier & Ives and other printing firms.

As soon as both lettering and drawing were rendered in crayon, another worker would apply an acid solution to the stone’s surface to prepare the image for printing. Dilute nitric acid was used to “bite” the limestone and fix the image to the stone, and a thin layer of gum arabic prevented further grease from settling on the surface. Lithography operates on the principle that grease and water repel each other: for each impression the printer would dampen the stone’s surface with water, then use a roller to apply the Currier & Ives’s proprietary recipe for grease-based ink, which would adhere only to the design in crayon. Finally the printer would lay a damp sheet of paper over the stone and use the pressure of an iron plate to transfer the inked design to the paper. Although the stone would be re-inked for each impression, many prints could be pulled from a stone with little deterioration, facilitating large runs of designs.

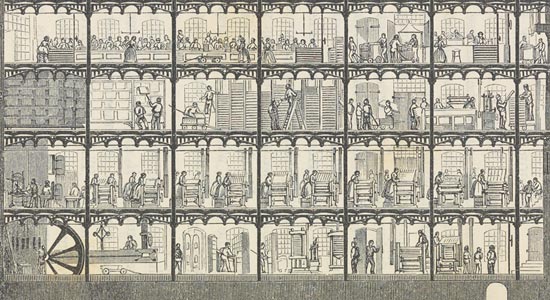

The division of labor within the printing shop made the process still more efficient. Although no images survive of the Currier & Ives fourth-floor printing space, a didactic image made by the Boston printmaker Louis Prang (fig. 2) in 1874 illustrates the specialized tasks seen in a small-scale lithography workshop. In reality the workshops of both Prang and Currier & Ives would have been much more crowded with workers and printing equipment; this illustration nevertheless effectively paraphrases the steps in the lithography process. At left a worker grinds down a previously used stone in order to prepare the surface for a new image. As good limestone was, and still is, relatively precious, stones were readily recycled as the designs they printed outwore their popularity. In the center an artist works on a stone, copying his design from an existing painting. The acid solution sits ready in the foreground, while the worker on the right rolls ink onto a stone sitting on a hand-operated press. Although mechanized printing processes developed later in the nineteenth century, Currier & Ives remained staunchly faithful to this older method.

Currier & Ives’s approach to coloring was similarly conservative. Whereas firms such as Louis Prang’s exploited the new technology of chromolithography, using multiple stones to print a variety of colors, Currier & Ives relied primarily on skilled manual labor to create fairly standardized but essentially unique prints. Once the black ink had dried on a set of prints, they would be transported to the building’s fifth floor, where a team of mostly German immigrant girls applied watercolor washes to each individual impression. Sitting at a long bench, these female colorists worked from a model print, usually colored by one of the firm’s resident artists. Each worker was responsible for an individual color in each print. This assembly-line technique could be streamlined in the event of a rush order by using a stencil for each color, although clipper ship images likely did not fall into this category. A print from a similar clipper ship stone (fig. 3) shows the hand-coloring typical of this genre, although it is significantly faded. Moreover, one can detect subtle differences in the blue wash on two prints pulled from the stone in this exhibit, which highlight the small idiosyncrasies that lent these prints the sense of an artist’s hand. Currier & Ives was also known to preserve a popular design on stone and repurpose it later with additional coloring. For instance, an 1858 print of the burning of the New York Crystal Palace reuses the same stone by Fanny Palmer that had produced a more serene image of the fair’s 1853 inauguration. Incidentally, the New York Crystal Palace had featured a display delineating the steps of lithography for a general audience.

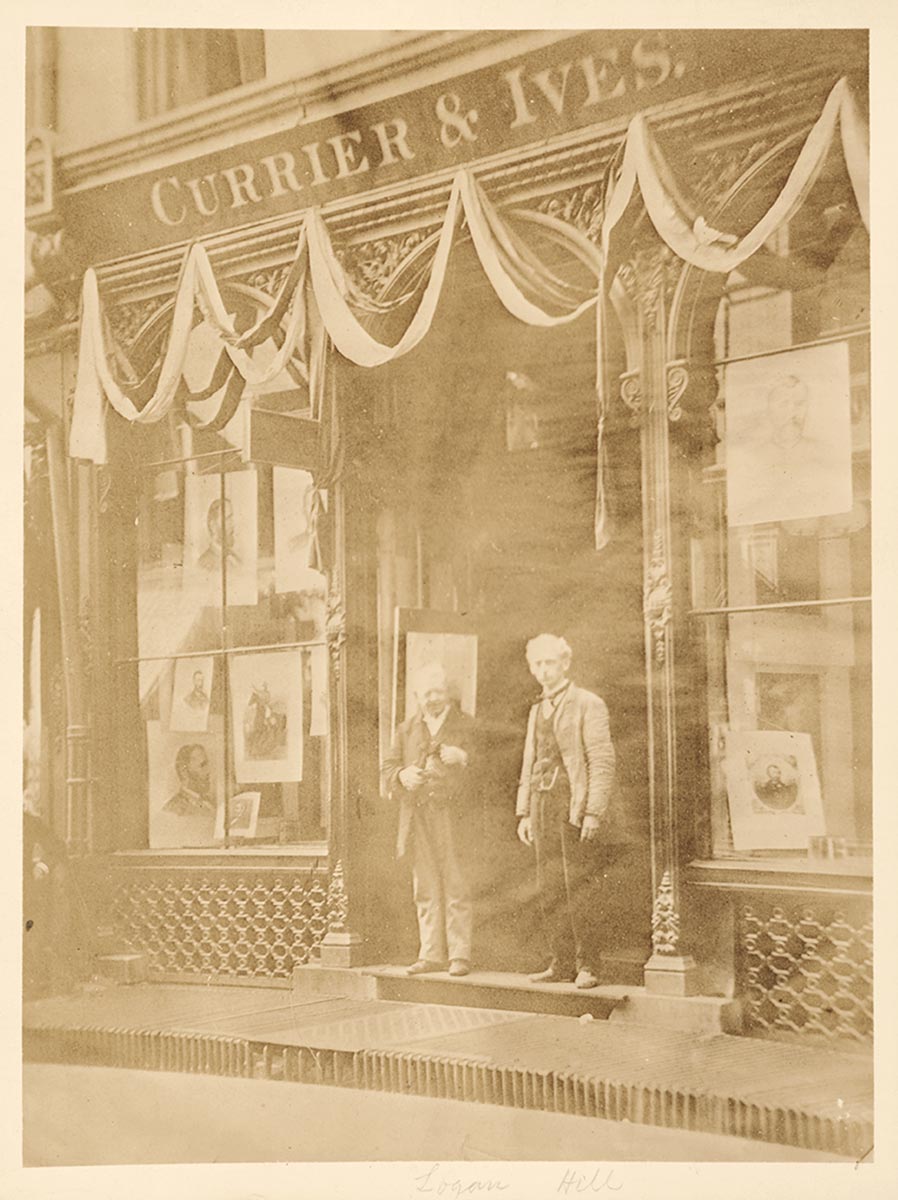

Once a print had been colored, touched up, and approved by a supervising “finisher” on the fifth floor, it was ready to sell, either in the Currier & Ives retail shop nearby on Nassau Street or by one of a number of pushcart salesmen. Between 1838 and 1872, such itinerant contractors would arrive at 152 Nassau Street each morning to collect a selection of prints in various sizes, which they would peddle on the streets. Although the prints were sold rolled and unframed, these hawkers might display one or two examples unfurled and tacked to the sides of their carts in order to attract customers in the busy streets of downtown New York City. Meanwhile, the Nassau Street shop served as the firm’s highly visible retail headquarters. A late-nineteenth-century photograph of the new location at 115 Nassau (fig. 4) shows various prints, mostly portraits, hung prominently in the storefront’s plate glass windows. Daniel Logan Sr., who served as retail manager for many years, appears in the doorway on the right.

Currier & Ives prominently marketed its products as “cheap and popular” pictures, both in New York and to an ever-expanding national international customer base. Surviving broadsides, newspaper advertisements, and catalogues indicate the firm’s espousal of an inclusive, democratic view of art, although their “Darktown” series admittedly represented racial caricatures uncomfortable to modern eyes. Currier & Ives’s stock encompassed a variety of genres and a range of price points, and even the firm’s largest folio prints were not beyond the means of middle-class customers seeking affordable decoration for the walls of their parlors. Such prints were equally popular in more public spaces like taverns and offices. Clipper ship prints peaked in popularity in the 1850s, when such maritime imagery connoted speed and technological innovation as much as it did mercantile wealth. Interestingly, these prints found a receptive audience in France as well.

Of course, these prints intended for a broad market were not without their critics. In an 1842 account of his American travels, Charles Dickens notes the spread of such images with some distaste:

So far, nearly every house is a low tavern; and on the barroom walls, are colored prints of Washington, and Queen Victoria of England, and the American Eagle. Among the pigeon holes that hold the bottles, are pieces of plate-glass and colored paper, for there is, in some sort, a taste for decoration, even here. And as seamen frequent these haunts, there are maritime pictures by the dozen: of partings between sailors and their lady-loves, portraits of William, of the ballad, and his Black-Eyed Susan; of Will Watch, the Bold Smuggler; of Paul Jones the Pirate, and the like; on which the painted eyes of Queen Victoria, and of Washington to boot, rest in as strange companionship, as on most of the scenes that are reenacted in their wondering presence.

Although he does not name Currier & Ives specifically, the uncomplicated, popular images that Dickens identifies would have integrated easily into Currier & Ives’s stock, alongside picturesque genre scenes, city views, and the representations of current events that first established the firm’s reputation.

Once abundant but ephemeral articles of material culture, Currier & Ives prints have become prized by collectors, particularly since the firm’s liquidation and Peters’s nostalgic retrospective. More recent appraisals of Currier & Ives have sought to break through the layer of sentimentality surrounding the firm, exposing the prints’ imagery as evidence of America’s aspirational self-representation. Nevertheless, the prints themselves have transformed from serially produced examples of popular designs to fairly unique historical documents, which today may be considered by some as works of fine art. Extant stones such as the one in this exhibit, however, remind us that Currier & Ives produced and distributed its prints as cheap decoration geared toward the growing middle class in New York and beyond. Furthermore, this stone’s material presence substantiates Currier & Ives’s legacy as one of New York’s leading visual entrepreneurs of the nineteenth century.