When photographer Victor Prevost immigrated to New York in 1848, he brought with him European photographic technology and aesthetic vision. Prevost’s architectural photographs suggest that New York could be understood through an “old world” lens—through the monuments, neoclassical buildings, churches, and other spaces that linked New York to the older capitals of Europe. Through this approach, Prevost demonstrated that while Napoleon III was constructing imperial monuments on the grands boulevards of Paris, New York was constructing a monumentality all its own, visible in the development of the dynamic cultural, commercial, and residential spaces that would come to define the Empire City.

Prevost’s training in painting and photography in France influenced his artistic perspective. Born in France in 1820, he studied at the École des Beaux Arts at the same time as the master photographer Gustave le Gray. However, Prevost left France for New York at the age of twenty-eight and worked for the New York branch of the French lithography firm of Goupil, Vibert, and Co., where he was soon described as “one of the best lithographers” at the firm. Prevost started experimenting with photography just as European photographic technology was advancing rapidly. Improving upon William Henry Fox Talbot’s “Talbotypes,” le Gray developed his own methods of producing wax-paper negatives (calotypes) in 1850, and Prevost soon after picked up his former classmate’s techniques. These calotypes had the advantage of being remarkably clear, as well as infinitely reproducible, unlike daguerreotypes. About 1852 Prevost made a critical trip back to France, where he likely entered the circle of French photographers working on the Mission Héliographique, an inventory of the architectural patrimony of France. Prevost’s photographs of French architectural monuments bore great similarities to those of the group around Le Gray. Upon his return to New York, Prevost’s work recalled much of the style, technique, and romanticism of his French counterparts.

Prevost opened a studio at 624 Broadway with Frenchman Pierre Duchochois in 1853, and within a year the Photographic and Fine Art Journal listed him as the most experienced calotype photographer in New York. His most prolific photographic project was a collection of thirty-six unpublished New York architectural views made from 1853 to 1856. Prevost had turned his lens to the new urban landscape of his adopted city, producing an assortment of photographs that show remarkable detail and clarity, reminiscent of the images being produced in France. But far from just an encyclopedic architectural catalogue, Prevost’s photographs reflect his editorial intent, which becomes evident through an examination of certain cultural, commercial, and residential spaces that he documented.

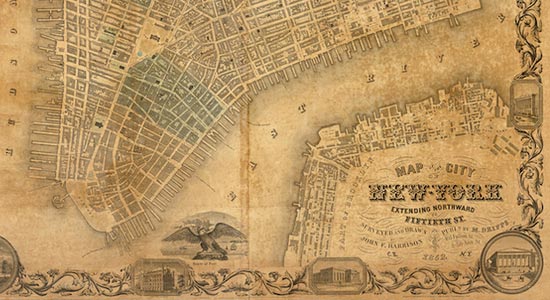

Fig. 1 Victor Prevost. Jeremiah Gurney’s Daguerrean Gallery at Broadway and Leonard Street, 1854. Modern gelatin silver print from waxed paper negative, 1854. Collection of The New-York Historical Society, PR56.21.1854.1.

+

Fig. 2 Victor Prevost. Charles Beck’s Store and Grace Church, 1854. Contact print made from Calotype negative. Collection of The New-York Historical Society, neg #26117.

+Provost’s photographs of cultural spaces illustrated how New York, like European cities, had important monuments and artists of its own. A principal subtheme in these photographs was the rapidly changing photography industry, which he illustrated through images of the daguerreotype galleries of his friends and colleagues. Jeremiah Gurney’s Daguerrean Gallery at Broadway and Leonard Street shows the studio of one of the pioneers of the early daguerreotyping industries in New York (fig. 1). He was known for his technical skill and his lifelike portraits of the New York cultural elite. At the time this photograph was taken in 1854, Prevost already knew Gurney’s partner, Charles DeForest Fredericks, a connection that would prove helpful to Prevost when his own photography studio shut down in 1855. Like the Société Héliographique in Paris, these New York daguerreotypists and photographers, despite competition among themselves, formed a cultural network into which Prevost fit comfortably, and he photographed other daguerrean studios, including those of Samuel Root and Mathew Brady. The Gurney photograph shows an elevated corner view taken from across the street. Prevost’s perspective emphasizes the monumental size of this five-story building, which towered over its four-story neighbors. It also shows the proliferation of signs along the front and side of the building that indicated the many interior-decorating wares that Gurney sold. Although the street appears devoid of people, there is a partially developed shadow of a horse and carriage just in front of the building, a hint of the usual bustling street life in this busy section of Broadway. By documenting the early photographic community and other artistic establishments, Prevost showed that New York was in the process of becoming a thriving cultural center in the nineteenth century.

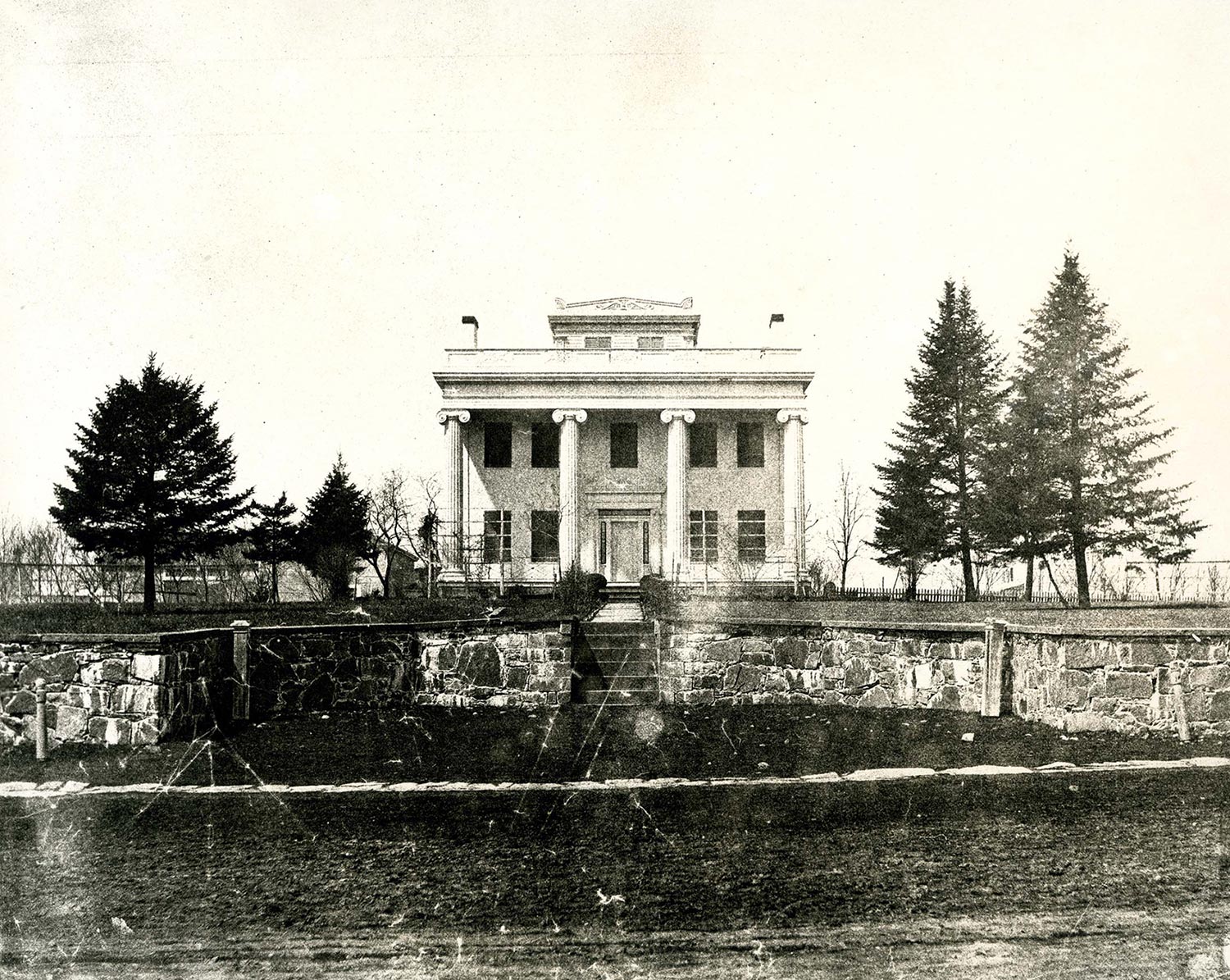

Fig. 3 Victor Prevost. Dr. Valentine Mott House, 94th Street and Bloomingdale Road, 1853–1855. Contact print made from calotype negative. Collection of The New-York Historical Society, neg #26142.

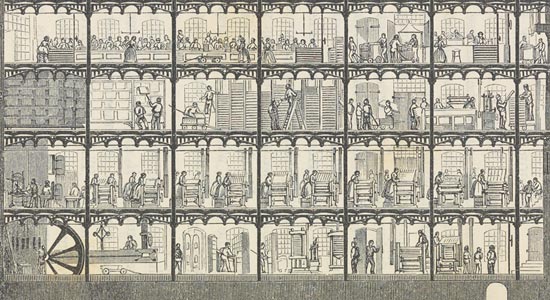

+The many changing retail facades on Broadway also interested Prevost, whose photographs showed how New York could compete with the cosmopolitan shopping districts of Europe. The photograph of Charles Beck’s Store and Grace Church is perhaps Prevost’s most striking representation of a commercial New York (fig. 2). He divided the composition of the image into two parts: Charles Beck’s retail store, located on Broadway and Ninth Street, and one side of Grace Church. The contrast is evident between the brilliant, unobscured whiteness of Beck’s store and the much grayer side of Grace Church, whose view is covered by shadow and trees. By juxtaposing a French Gothic-style church with a recently constructed commercial façade, Prevost suggests a social commentary on the proximity of secular and sacred buildings on Broadway. As his photographs show, these dynamic mixed spaces of commerce and religion characterized much of the urban development in mid-century New York. Prevost’s residential photographs also demonstrate themes of monumentality and urban development. These scenes liken New York to the palatial residences of Europe, while demonstrating the new growth in the city spurred by wealthy New Yorkers. Prevost’s Dr. Valentine Mott House, 94th Street and Bloomingdale Road, shows a summer house located at Bloomingdale Road (what is now Broadway) and Ninety-fourth Street (fig. 3). Prevost’s distant vantage point emphasizes the monumentality of the building’s neoclassical features. The symmetrical trees, expansive yard, and open sky situate this house in the largely undeveloped countryside that was upper Manhattan. The street here appears unfinished and rougher than the highly delineated paved streets of Lower Broadway. By emphasizing the monumental areas of New York, Prevost suggests that the city had a refined elite class whose estates contributed to the architectural patrimony of Manhattan. In addition, through emphasizing the sparsely populated areas of the city, Prevost suggested that much of New York had yet to be developed.

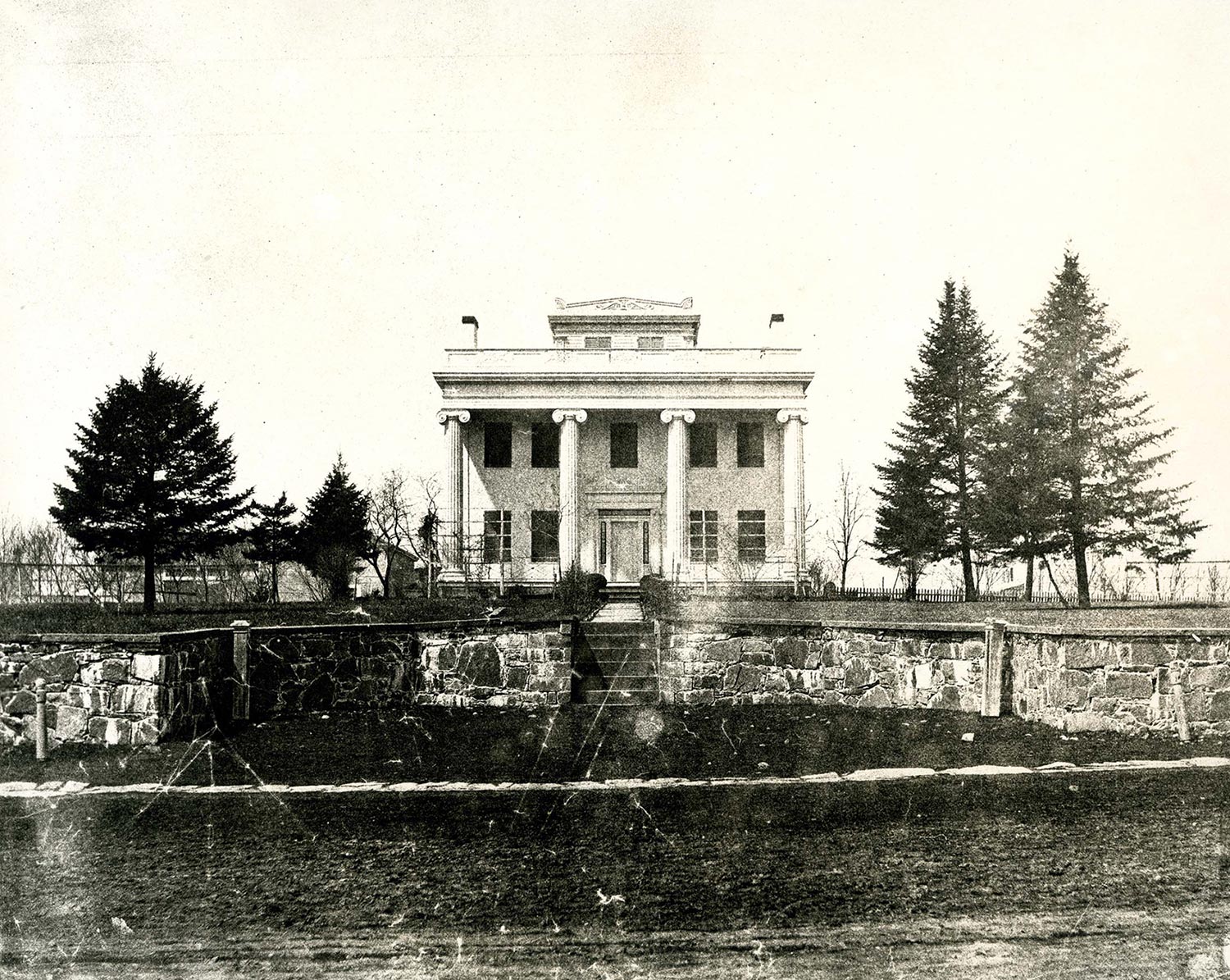

Fig. 4 Possibly Victor Prevost. Fredrick’s Photographic Temple of Art, 1857. Salt print from wet collodion negative. National Archives.

+Although Prevost never achieved commercial success, nor did he ever publish his architecture views for a wider audience, he enriched photographic practice in New York and left his mark on contemporary photographers, one of whom, Gurney’s partner Charles DeForest Fredericks, had hired Prevost in 1857 soon after meeting him in Paris. Frederick’s Photographic Temple of Art (fig. 4) is thought to have been taken by Prevost, since it illustrates the same technical skill and expert composition that characterizes Prevost’s architectural views of the city.

These architectural views present an important moment in the early history of photography and New York. They show the artistic vision of the immigrant Victor Prevost, who documented the city through a cultural lens reminiscent of his French counterparts. Through this lens, Prevost presented what he believed to be New York’s monuments in the making—its emerging artistic community that would give New York its cultural capital, its rapidly developing commercial centers that would fuel New York’s massive economy, and the palatial homes of its illustrious citizens who would greatly impact the city’s history.