An advertisement in the New York Evening Post of January 4, 1826 assures readers that the New-York Spectaculum, essentially a lesser Barnum’s American Museum, is not only “scientific” but is also a “place of resort to citizens and strangers, where a leisure hour can be passed in amusement and instruction.” Other commercial entertainments are described as “wholesome,” or suitable for families. The frequency of such justifications indicates a lingering cultural tendency to moralize leisure, and whereas it could be argued that this anxiety over the morality of amusement (theaters, circuses, sports clubs, dance halls, and even public dining establishments, which tended to be associated with such vices as gambling, promiscuity, drunkenness, and laziness) continued throughout the nineteenth century and into the following one, entertainment by the 1830s, was becoming a more acceptable way to spend free time. This change was visible in the newspapers of the day, which demonstrates a gradual shift in cultural attitudes about entertainment and leisure. In the fall of 1831, newspapers such as the New York Evening Post changed the heading of their leisure column from “Theatres” to “Amusements.” The word “theatre” indicates a stage and an audience, suggesting the act of looking, whereas “amusements” does not refer to any particular sensory action or activity.The language used in an advertisement for Peale’s Museum in the New York Evening Post on February 4, 1832, is nothing short of sensational, stating that visitors could see an anaconda being fed a live animal, “which it destroys in its folds, and then swallows whole.”

“Perceptive vigilance” and “the responsibility of republican citizens,” as art historian Wendy Bellion points out were important in establishing a sense of unity in the new nation, especially as its character shifted toward industry and large cities, where one’s powers of perception would be put to the test. Good citizens would have to recognize each other not through personal relationships, but by being engaged in a common act of looking. Thus visual entertainments, from panoramic and other trompe l’oeil paintings to tableaux vivants, and mechanical devices, such as automata, represented an opportunity to demonstrate this politicized perceptiveness and were important forms of amusement in the early republic. These were all still being offered in downtown New York in the 1820s and 1830s, but by this time the act of seeing was less important in terms of the exercise of republican virtue than it was as a way of recognizing and perpetuating class identity.

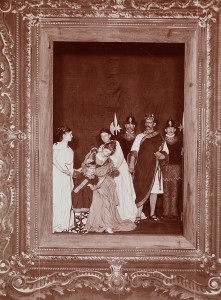

Fig. 1 Byron Company. A tableau vivant of a Roman scene, 1897. Gelatin silver print. Museum of the City of New York, 93.1.1.18352.

+An 1897 photograph by the Byron Company depicts a group in fancy dress, posed as a tableau vivant, a type of entertainment ideal for class-based display (fig. 1). Tableaux vivants, first popularized in New York in the late 1830s, were originally parlor entertainments that involved the dramatic recreation of scenes from paintings, history, current events, or the theater. Allegories of virtues were also popular themes. These elaborate entertainments were sometimes presented as guessing games and were often put on for holidays or charity benefits. New York’s active commercial culture and its entrepreneurs quickly seized on the possibilities of bringing the tableau vivant to the public. Throughout the next few decades, tableaux vivants could be found in pleasure gardens such as Niblo’s and the Castle Garden; in Barnum’s American Museum; in cheap theaters, entertainment halls, and curiosity museums; and at special events, including festivals, pageants, and political gatherings. As with parodies and pastiches, the audience had to know the reference to fully appreciate the tableau, although those who did not could still have appreciated the pleasing aesthetics. The tableau vivant form was therefore able to transcend class barriers, although the highbrow-lowbrow distinction did not always pertain to economic level, as the club and popular theater scene belies. In public areas such as clubs or theaters the tableau vivant form was frequently an excuse for the display of women appearing in the nude, or nearly so. The statuary form of tableau, “considered the most beautiful given,” also happened to feature women impersonating classical figures wearing little more than draped cotton sheets. The same gentlemen who watched or participated in tableaux vivants of highbrow scenes at home, might be found later at clubs enjoying what would be more considered a less refined sort of tableau.

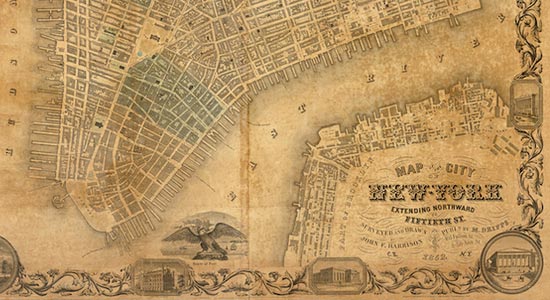

Fig. 2 Thomas Benecke. Sleighing in New York, 1855. Chromolithograph with hand-coloring, printed by Nagel and Lewis, published by Emile Seitz. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Edward W. C. Arnold Collection of New York Prints, Maps and Pictures, Bequest of Edward W. C. Arnold, 1954 (54.90.1061).

+

Fig. 3 Sarony, Major, and Knapp. The Palace Garden, cover illustration for “The Palace Garden Polka” by Horace Waters, 1858. Chromolithograph. Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University.

+The tableau vivant was primarily an urban phenomenon, since living in a city made it much more convenient to put on a production and have access to the cultural capital necessary to grasp a wider range of references. The tableau vivant form also proved helpful in breaking down the bustle of the city into easily processed vignettes, a particularly useful compositional structure for pictures of busy New York City streets. Notice how this is done to make visual sense of the chaos in Thomas Benecke’s 1855 theatrical depiction of Broadway. Barnum’s American Museum can be seen the background (fig. 2). By the last few decades of the century, illustrated newspapers sometimes referred to their scenes of everyday life as “a tableau vivant,” condensing the unstaged, on-the-street encounter into a theatrical scene, a format easily understandable to the viewer. Any picturesque or noteworthy scene might be described as a “tableau vivant.” This was an especially common literary device, helping readers to create a mental image, stylized and often sentimental, from the written word.

Although the widening divide between the moneyed and the poor in America engendered greater emulation of European class-based social structures, the shift of the tableau vivant from the parlor to the public helped usher in a new era of commercial entertainment. Leisure, an occasion for expressing and confirming one’s group identity, became an increasingly public pursuit throughout the nineteenth century. The rise of new kinds of commercialized leisure cemented the division of New York social life into “high” and “low,” with activities and locations sharply segregated by class, and then further divided by gender and ethnicity.

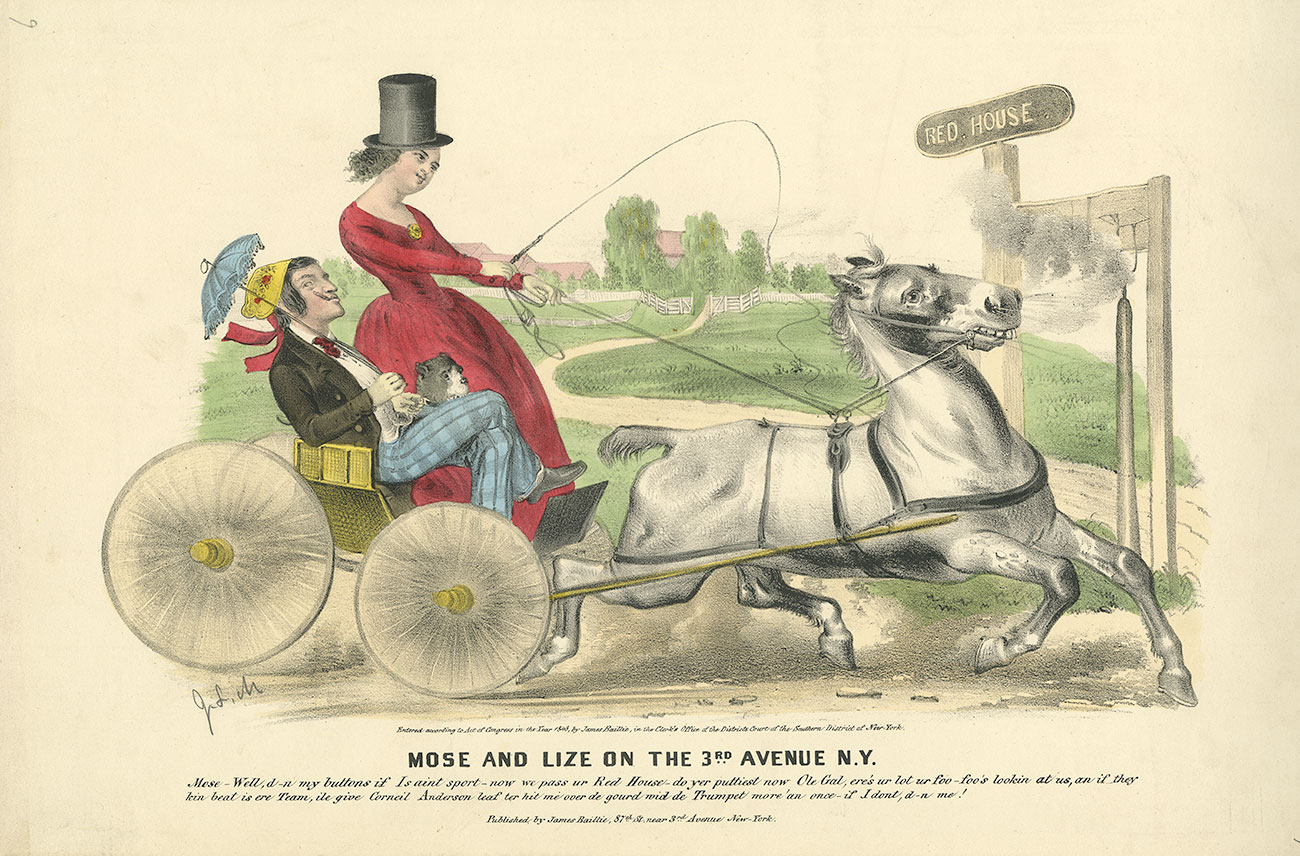

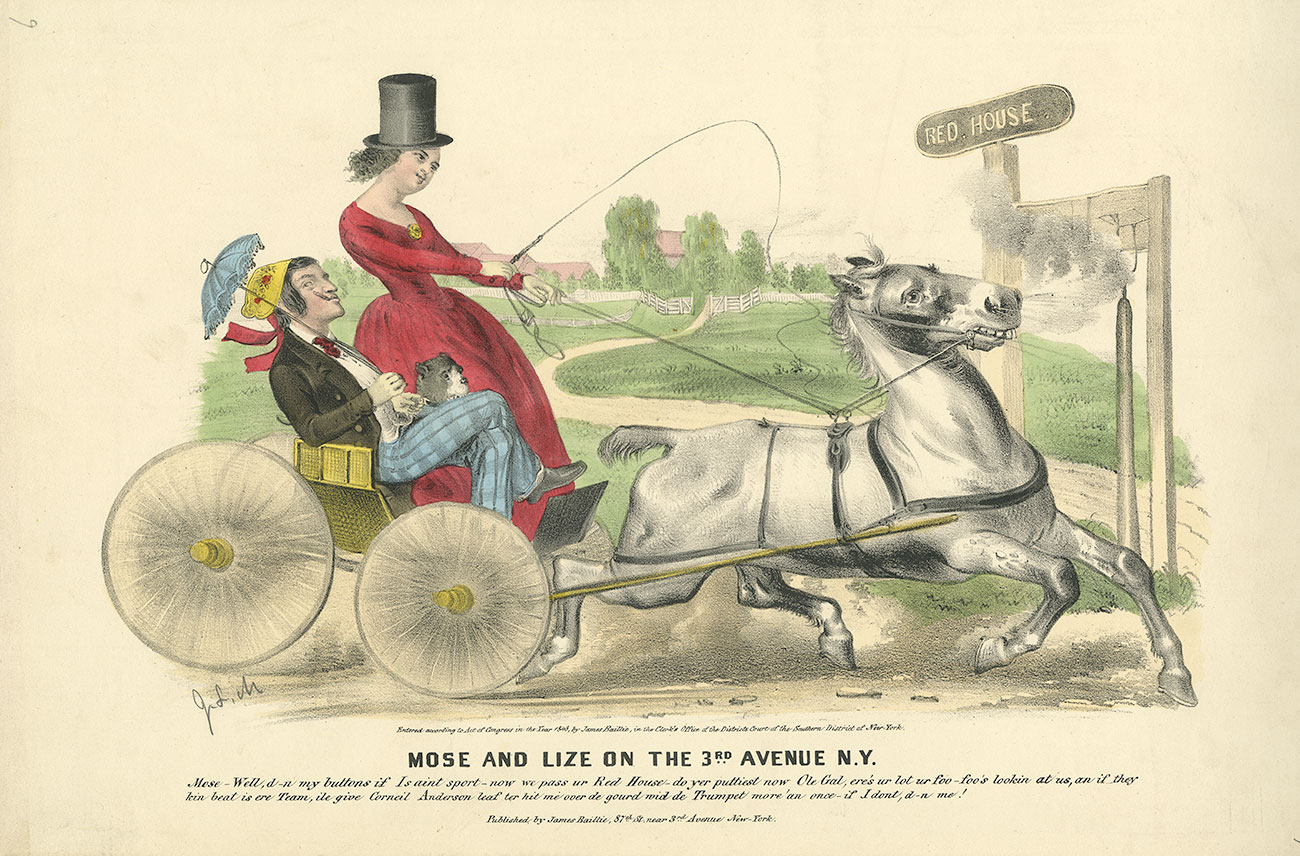

Fig. 4 James Baillie. Mose and Lize on the 3rd Avenue, N.Y., 1848. Chromolithograph. Collection of The New-York Historical Society, neg#58614.

+Seeing and being seen were particularly important to New York social life, whether it was the elite promenade down Broadway (see Brow, Fashion and Urban Living) or in the downtown pleasure gardens that moved uptown as areas around the Bowery and the Battery became lower-class neighborhoods to accommodate New York’s burgeoning immigrant population with their own entertainment traditions, such as beer gardens and concert saloons. Well-dressed men and women engage in the display of genteel behavior in the 1858 Sardony, Major, and Knapp colored lithograph of the Palace Garden, a newly opened pleasure garden at Sixth Avenue between Fourteenth and Fifteenth Streets (fig. 3). In contrast, Moze and Lize, two caricatures representing a Bowery B’hoy and G’hal, a certain lower-class and counter-cultural- social “type,” defy bourgeois social norms by engaging in the raucous entertainment of horse racing (fig. 4). The sign reads “Red House”; the newly macadamized Third Avenue inspired young men to race their horses between Red House and Hazard House, two uptown hotels. Horse racing, or “trotting” in the parlance of the day, was a spectator sport for the elite, but the official trotting club comprised lower- and working-class men, primarily butchers. Note also the swapping of fashion accessories and roles as passenger and driver, which hint at gender transgressions intended to indicate the dissolution of social norms and gentility among the lower classes. The gender divide is rigidly upheld in depictions of upper-class leisure. In the Palace Garden lithograph, the women in their brightly colored, bell-shaped dresses ornamented with rows of flounces look like blossoms, in dramatic contrast to the restrained, dark palette of men’s fashion with its narrow silhouettes.

By the end of the century, when the photograph depicting the Roman scene (fig. 1) was taken, tableaux vivants were seen as nostalgic throwbacks to a simpler time, when families amused themselves inside the home and not at commercial places of entertainment. Commercialized amusements such as vaudeville and dime museums in the late nineteenth century had made leisure more accessible to all classes. Not everyone was happy with this situation, as attested by an article in the New York Evangelist from January 12, 1860 that tried to ban skating (an activity nearly everyone could afford) in Central Park on Sundays, but commercial entertainment was here to stay.