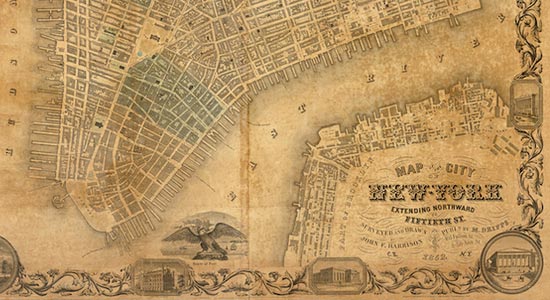

Fig. 1 Thomas Hogan. “Up Among the Nineties.” From Harper’s Weekly, August 15, 1868. Library, Bard Graduate Center. Photographer: Bruce White.

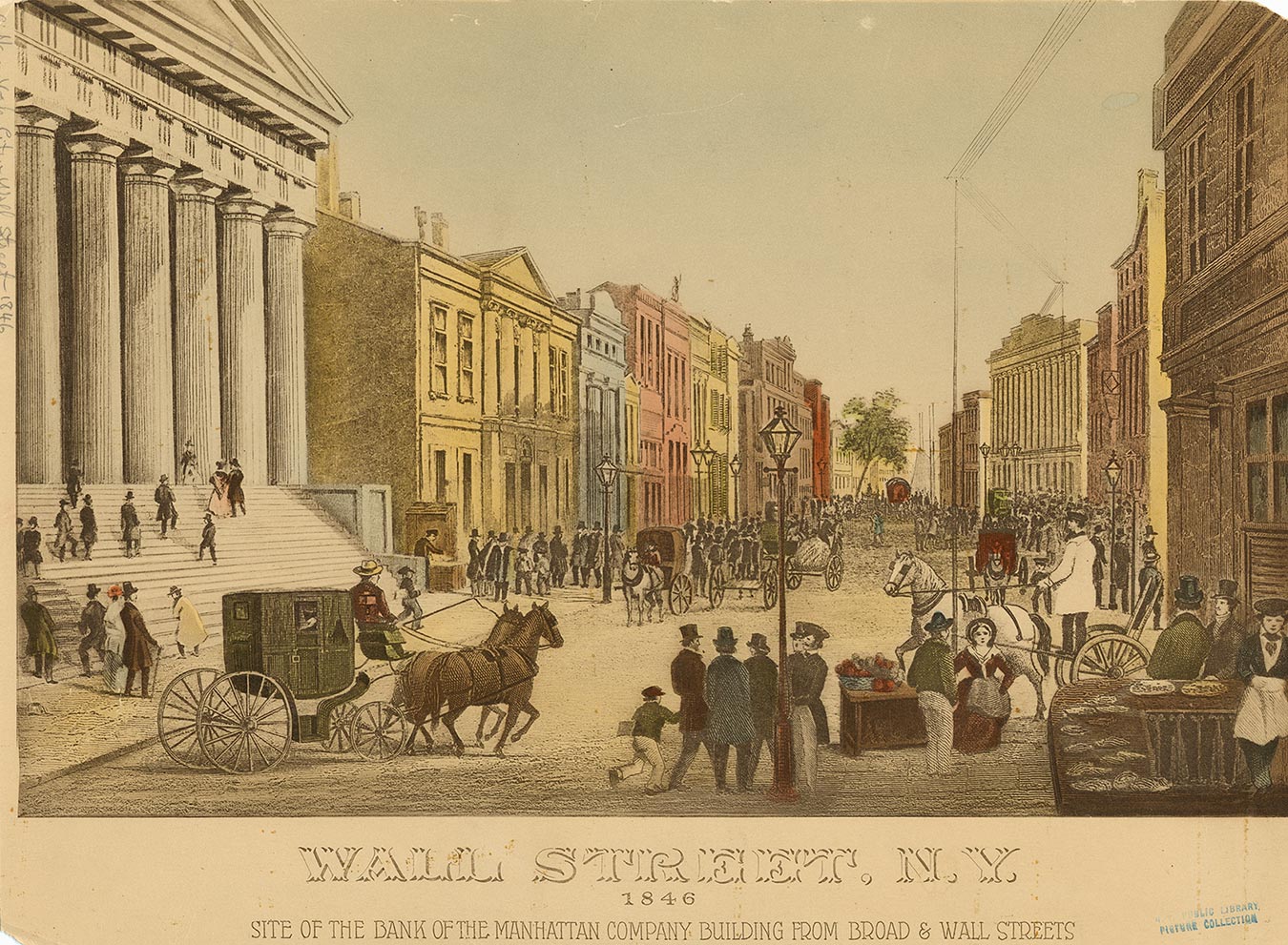

One significant feature of the nineteenth-century illustrated press was its tendency to publish stark depictions of the unrefined urban poor in contrast to genteel depictions of the middle class. Historian Joshua Brown suggests that through these images “the threatening urban landscape could be read and, with this knowledge, safely traversed” for both the high and low ends of society. Indeed, an illustration published in Harper’s Weekly in 1868 confirms this great divide between the “two great classes of the metropolis” (fig. 1) but also reveals that a shared palate—in this case, a taste for ice cream—inextricably bound them as well. Here the icy confection offers a brief respite from the brutal heat of a New York summer, although it is being consumed in wildly different contexts. At the left, stylish ladies and gentlemen gather inside a posh Broadway eating establishment seated around a dignified table; at the right, unkempt young children wearing shabby clothes and no shoes assemble outside around a lowly Bowery street vendor. Although it is indicative of the growing disparities between the two classes, ice cream consumption in this image is also used to signify that the boundaries between rich and poor were in fact quite amorphous, as the classes could be joined in their frenzied consumption (and enjoyment) of ice cream. At the same time, that common pursuit provided all the more reason for such portrayals as Harper’s, where class distinctions could be made as to how and where that ice cream consumption occurred.

Fig. 2 Dan Beard. “Opening of the Oyster Season.” From Harper’s Weekly, September 16, 1882. HarpWeek, LLC.

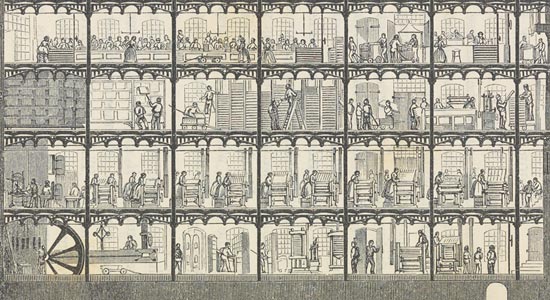

+This brand of New York egalitarianism is probably seen most clearly in depictions of oyster consumption. Known today as a relatively luxurious treat, these beloved mollusks were enjoyed by everyone in nineteenth-century New York, even as images of their consumption reveal deep differences in the social geography of the city. Oysters “were true New Yorkers,” historian Mark Kurlansky noted in his book The Big Oyster. “They were food for gourmets, gourmands, and those who were simply hungry; tantalizing the wealthy in stately homes and sustaining the poor in wretched slums.” Long before French-style white tablecloth restaurants like Delmonico’s became popular with the high end of New York society, the oyster cellars (also known as saloons), located along densely populated thoroughfares like Canal Street, and the oyster stands, in the city’s bustling food markets and busy commercial centers, drew a diverse clientele from all levels of society. “There is scarcely a square without several oyster-saloons; they are aboveground and underground, in shanties and palaces,” the author George Makepeace Towle noted in 1870. “For tenpence you may have a large dish of them, done in any style you will, and as many as you can consume. The restaurants—ostentatious and humble—are in the season crowded with oyster lovers: ladies and gentleman, workmen and seamstresses resort to them in multitudes, and for a trifle may have a right royal feast.” A century earlier, when a “primitive” oyster saloon opened up in 1763 on Broad Street, no one could have predicted that an entire industry would spring up around this bivalve mollusk—or the countless ways in which New Yorkers both rich and poor would consume them (fig. 2).

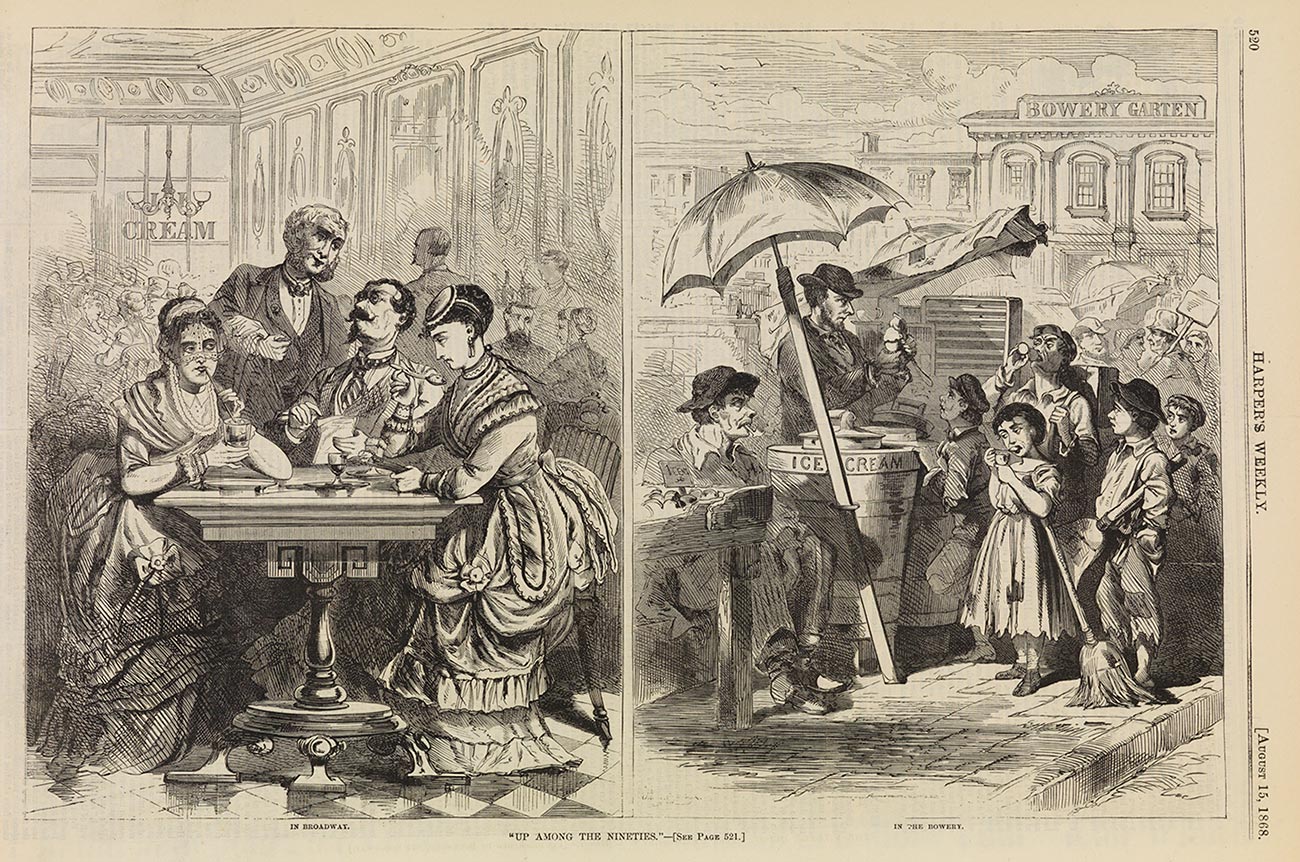

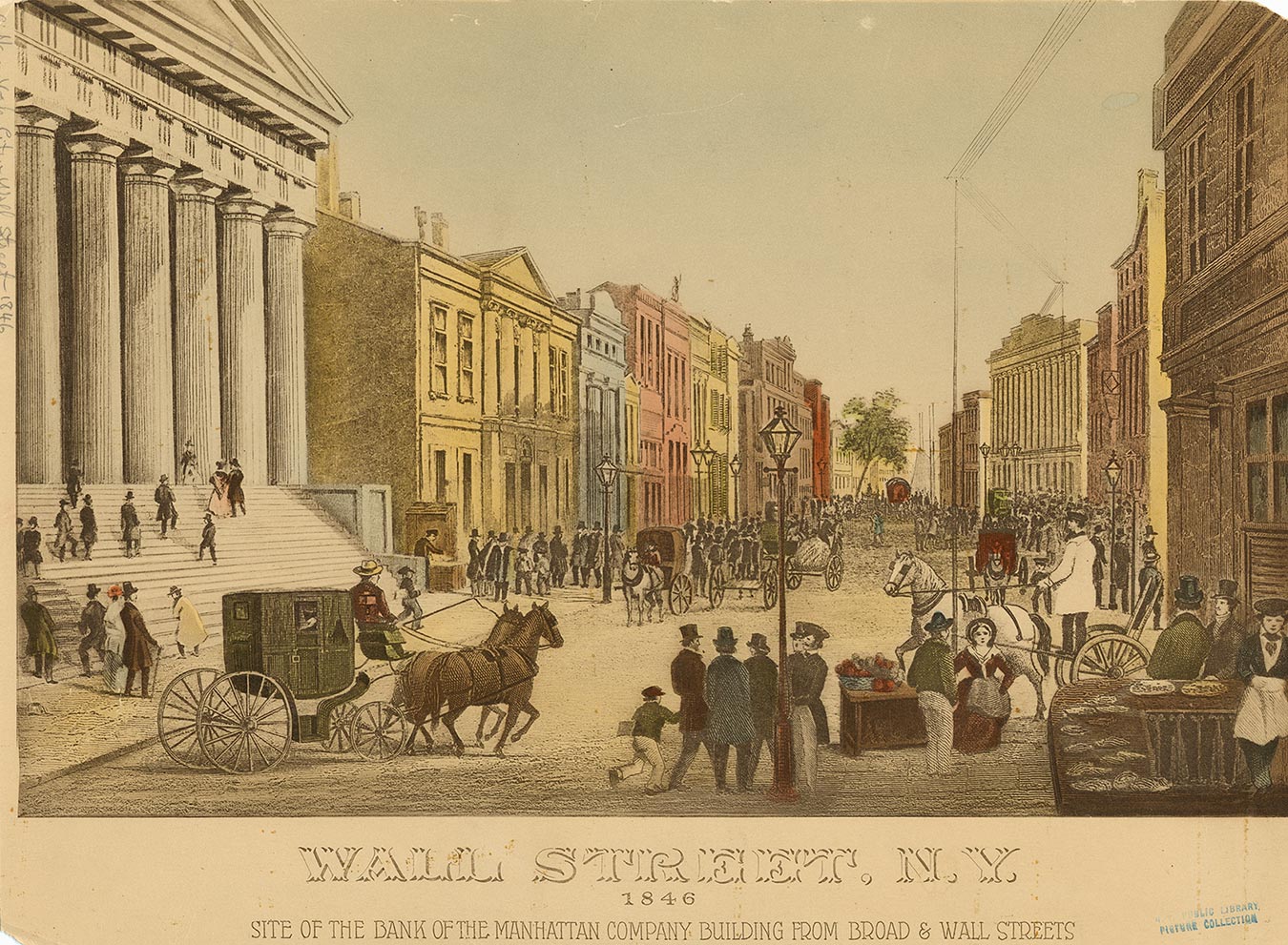

Fig. 3 Wall Street, N.Y., 1846. Aquatint. Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

+The post-Erie Canal economic boom and the city’s growing geographic segmentation into discrete neighborhoods made it harder for working people to return home for lunch. Eating establishments thrived by offering quick meals that appealed to upper-class businessmen and workers short on time, and oysters were a perfect choice, as they could be served and eaten quickly. The oyster stands that dotted the streets at lunchtime and operated in the city’s markets were frequented by members of both the high and low classes of society. In an 1846 depiction of Wall Street (fig. 3), an oyster stand in the lower right-hand corner appears poised and ready for the lunchtime rush of stock exchange traders and businessmen. In Nicolino Calyo’s watercolor (fig. 4) from the 1840s, a similar stand with its respectable oyster purveyor named Patrick Bryant in his slick black top hat serves up a large plate of oysters to a shabbily dressed patron. Although this image clearly demonstrates the success of oyster vendors, it also highlights the importance of this bivalve in feeding the rich and the poor in the rapidly urbanizing pre-Civil War city.

Fig. 4 Nicolino Calyo. “New York Street Cries: The Oyster-Stand,” 1840–44. Watercolor on paper. Museum of the City of New York.

+Nevertheless, class associations persisted in the city’s segmented food culture. The contrast in dining experiences extended to the oyster cellar, which “ranged from shady to refined,” as historian Cindy Lobel contends. “The oyster cellars of antebellum New York were that era’s counterpart to today’s pizza parlors.” Whereas the food was the same, frequently offered for about the same price, the surroundings differed dramatically: the wealthy dined in exclusive oyster saloons catering to their own kind, while the working classes patronized seedy oyster dens in less respectable parts of town. These class associations were defined by their neighborhoods; an upper-class client would not frequent an establishment in a slum like Five Points, just as a poor laborer would not be seen at an elite Wall Street stand.

Fig. 5 Fernando Miranda. “New York City — Fulton market in the fruit season—‘Here they are! Ripe watermelons—fine savannahs, fresh and sweet! Only five cents a slice! Step right up gentlemen!’” From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, September 4, 1875. Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

+However, the city’s hectic markets represented a great convergence of the “two great classes” over a shared love of oysters, indicating that the boundaries so clearly delineated by the illustrated press were more readily traversed than they appeared to be in print. City markets, including the Fulton Street market, built in 1816, were vital centers of commerce for rich and poor alike in the nineteenth century. These markets offered fresh foods to take away, but some of the city’s most famous oyster vendors also operated there. As one English visitor noted:

Fulton market is famous for its oysters and Dorlan is the oyster man of all others. . . . The people you meet at Delmonico’s, you see at Dorlan’s—men of wealth, and women of society; fastidious scholars and authors of renown . . . every body, high, low and middle in station, are patrons of the market. . . . If you wish to see one of the peculiar phases of New-York life, go to Dorlan’s at lunch time, and observe, amid its clatter and confusion, what fair and expensively attired women, what distinguished and gilded men, you will meet there. . . . Fulton market has a history in itself, and Dorlan is its central and commanding figure.

The sheer number of oyster purveyors at market is apparent in an 1875 depiction of the Fulton market in summer (fig. 5) from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. Here a ravenous bunch of mainly working-class watermelon consumers are pictured in front of signs advertising “Ladies and Gents Oyster Saloon.” The perception here is that the working class is consuming on the street, reinforcing the obsession of the illustrated press with the chasm between rich and poor. Clearly, the interest in defining urban types in mixed spaces like the markets was in some respects a way to mediate behavioral norms and expected decorum in a public setting for both the high and low ends of society. But it also illustrates the energetic environment in which urban types were mixing and the variety of foods and experiences on display within the market itself.

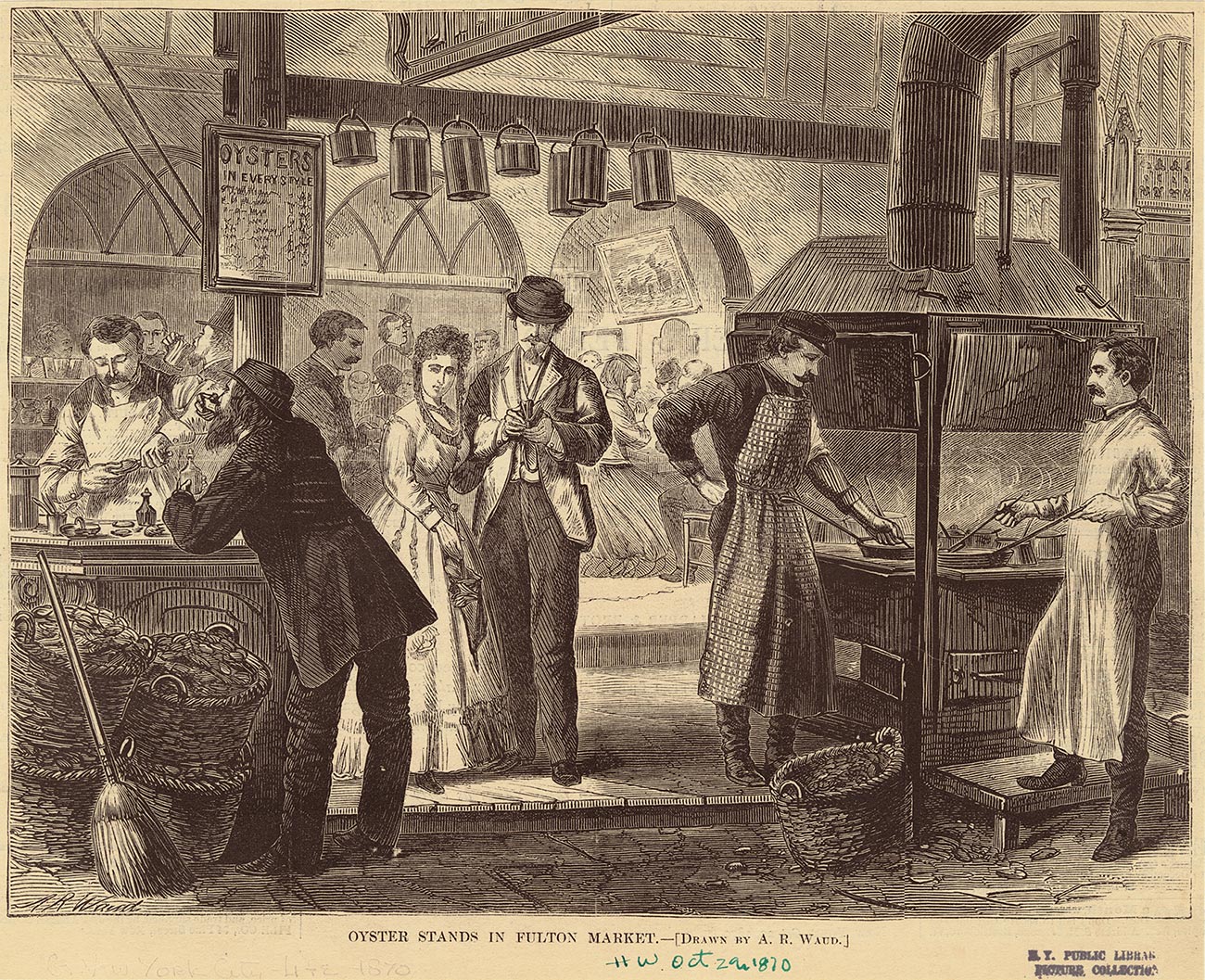

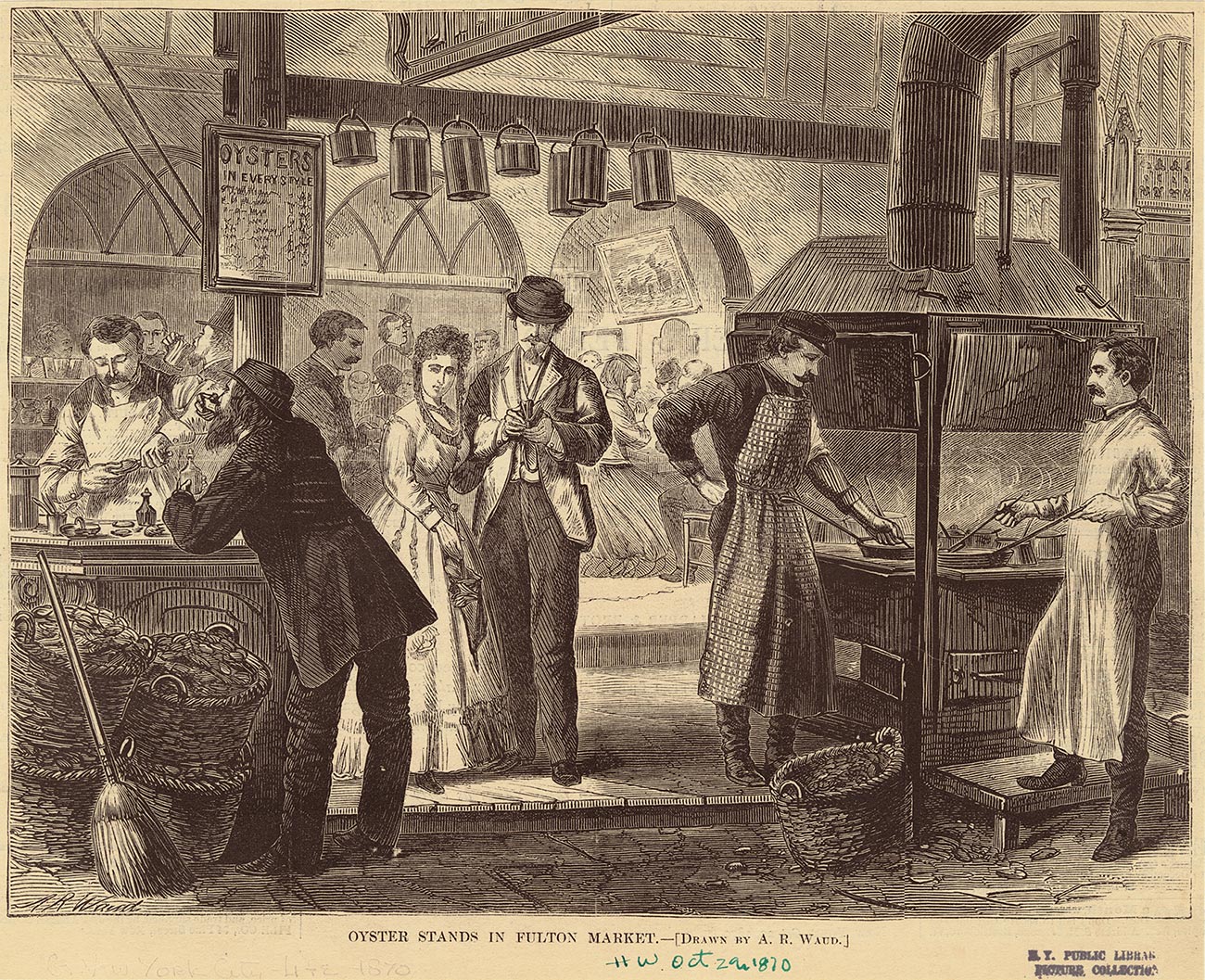

Fig. 6 Alfred R. Waud. “Oyster stands in Fulton Market.” From Harper’s Weekly, October 29, 1870. Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

+An 1870 print from Harper’s Weekly (fig. 6) focuses on the visual spectacle of the oyster stands in the Fulton Street market, where a mix of social types dot the landscape. Well-dressed ladies, commonly excluded from gentlemen’s dining establishments, mingle, albeit timidly, alongside male diners from all walks of life. Most eating establishments catered primarily to men, but women were often seen at the markets, although their mingling with men was sometimes perceived as indecent. Lobel contends that many of the market oyster stands appealed to late-night middle-class revelers who lived in the suburb of Brooklyn, and indeed, the Fulton market was conveniently located near the 24-hour Brooklyn ferry. But the stands also appealed to the same lunchtime businessmen who commuted from afar to get to work. As this scene suggests, oyster stands in the market were one of the few places where rich and poor—as well as men and women—were depicted alongside one another in the mainstream illustrated press. It also alludes to the ways in which the theme of the “divided” city was in fact an inaccurate portrayal of a city where the classes did intermingle, thrown together in the chaotic metropolis at times, as their oyster consumption at the market or their use of streetcars illustrate.

At first glance, the Harper’s image “Up Among the Nineties” (a reference to the summer heat) appears to illustrate a dramatic contrast between toffs and urchins, but in fact it reveals a food culture shared by rich and poor. While fine dining and high-end oyster saloons were preferred by wealthy New Yorkers in the nineteenth century, no one was above sitting down to a meal of New York harbor’s freshest bivalves at Dorlon’s in the Fulton Street market. New York was a socially complex city, where the sometimes flexible boundaries between the classes existed in ways far more complex than the mainstream illustrated press represented. Of course, the illustrated press sought to sell newspapers and their sensationalist images promised, well before Jacob Riis and his How the Other Half Lives, a glimpse of areas unknown and unknowable to the ordinary middle-class reader.