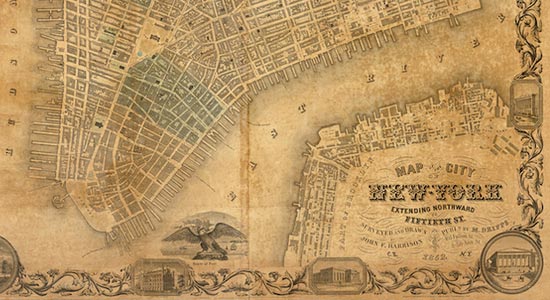

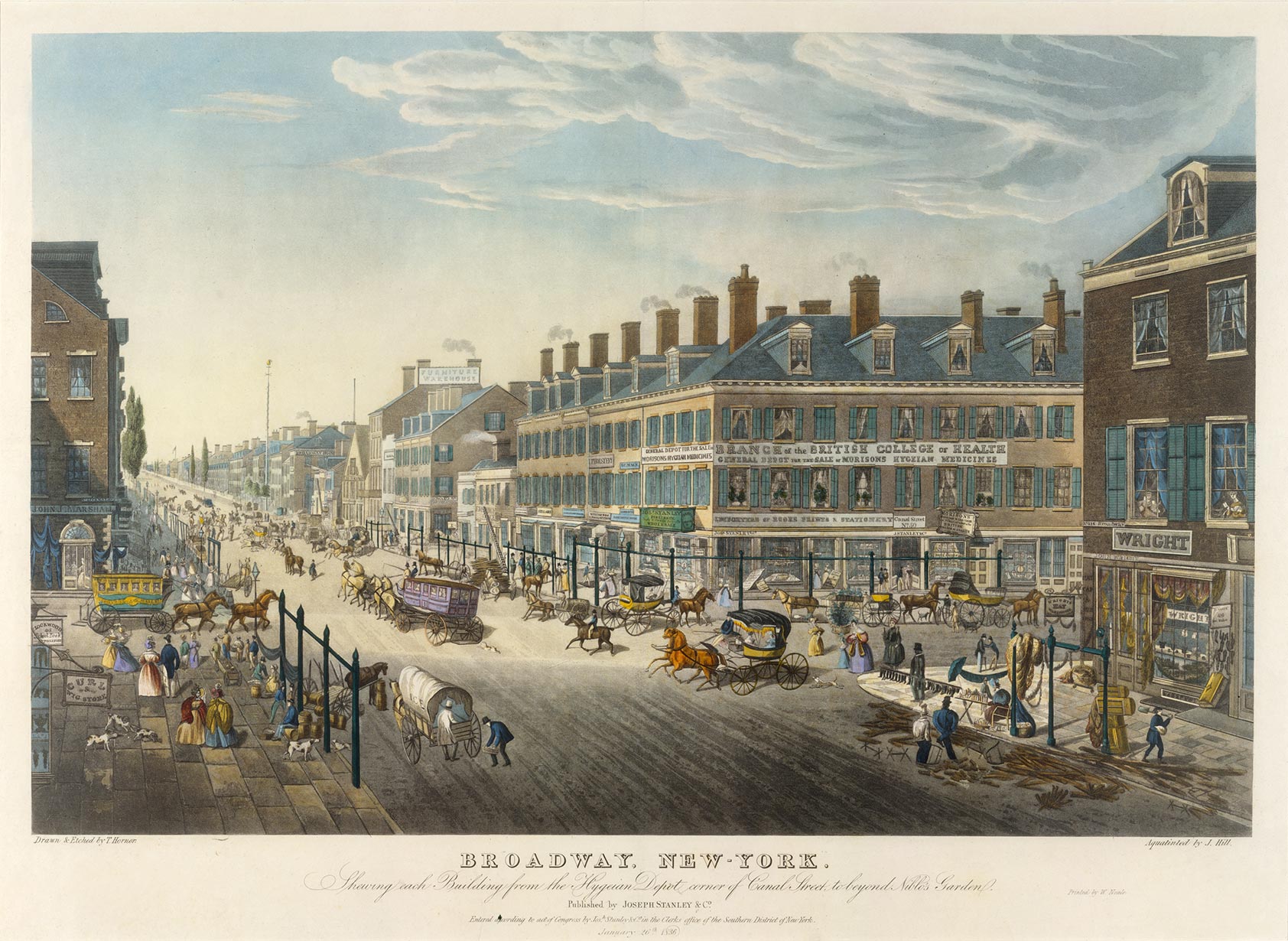

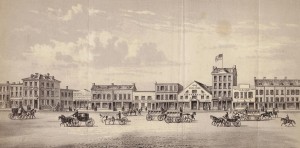

Fig. 1 Thomas Hornor. Broadway, New-York. Shewing Each Building from the Hygeian Depot Corner of Canal Street to beyond Niblo’s Garden, 1836. Aquatint and etching with hand-coloring, aquatint by John William Hill, printed by W. Neale, New York, published by Joseph Stanley & Co., New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Edward W. C. Arnold Collection of New York Prints, Maps and Pictures, Bequest of Edward W. C. Arnold, 1954 (54.90.703).

When in 1836 the recent immigrant Thomas Hornor illustrated the most recent center of commerce in New York—Broadway and Canal Street—he attempted to capture the contrasts of chaos and order that made the place such a vibrant hub of activity. Commissioned possibly as an advertisement by publisher Joseph Stanley, whose business is prominently depicted just below the Branch of the British College of Health at the center of the image, Hornor’s aquatint (fig. 1) offers a detailed view of his newly adopted home. He seems to be making an effort to justify the disorder of Manhattan’s bustling thoroughfares by piecing together a complex and chaotic iconography of commerce in action—including large signs, mismatched architecture, and an array of people—yet the overall impression depicts the grandeur and civility with which the city seemingly conducted the business of daily shop life. This orderly approach mirrors the gridded street structure established by the Commissioner’s Plan of 1811, which presumably helped to orient the viewer. But the image itself also reflects the actual atmosphere of this intersection, which resulted from New York’s economic boom after the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825. New York had only recently surpassed Philadelphia as the nation’s largest city and had become the center of a new American consumer-oriented culture. Hornor’s image may have been an attempt to make sense of the chaotic nature of commercial New York by depicting street life at this intersection as a series of orderly and refined vignettes rather than as the bustling place it most likely was.

Hornor was no stranger to the task of documenting the urban scene. A well-regarded land surveyor in London, he was a master of the illustrated map, an eighteenth-century art form that incorporated traditional mapping techniques with figural illustration. Despite criticism from his peers, he argued that the illustrated map was a time-honored and worthy enterprise that incorporated the exacting skills of the surveyor with the hand of the artist and appealed to wealthy patrons, who displayed such map-print hybrids in their homes as status symbols. His early years were marked by some success, but his fortunes tumbled when his ambitious plan to produce a 360-degree view of the London skyline, a kind of illustrated map that had to be scrapped for lack of money. As historian John Brewer notes, Hornor’s hyperrealistic Colosseum, as the London panorama project became known, paradoxically idealized the city as visual spectacle, as if documented by an “omniscient viewer” with an eye for visual perfection. As curator and panorama scholar Ralph Hyde suggests, Hornor’s ingenious skill as a surveyor was apparent in his ability to document the landscape of the London skyline, but his effort to visualize the street-level commercial spectacle was defined by “visual gimmickry.” In essence, his romanticization of chaos against a system of rational order cost him his career. Notable critics such as Charles Dickens slammed the inaccuracies of the project, and with no money left to continue his work, Hornor was forced to escape his debts in 1829 and flee to New York.

In an effort to establish himself as an accomplished printmaker in New York, Hornor took on the project of documenting the intersection of Broadway and Canal for Joseph Stanley, producing an image that is one of only two extant examples of his work in America. His interpretation of the intersection reads like a view of Broadway by a visitor consumed by the wonder and visual stimulation of the scene. Indeed, the city’s leading boulevard was a sight to see, as one English visitor noted: “The moving panorama of human life, as daily seen on the Broadway Pave [street], presents a curious and interesting picture to the student of ethnology. There you may see the lean lanky Puritan from the east, with keen eye and demure aspect, rubbing shoulders with a coloured dandy, whose ebony figures are hooped in gold.” As the city grew, Broadway marched ever northward, bringing along with it the commercial vivacity that had marked the street from its earliest Dutch days when Bowling Green and the very tip of lower Manhattan were the city’s hub of commercial enterprise.

For Hornor, such a visual feast for the eyes must have been a daunting project, as there was no rational, obvious perspective from which to depict a survey of his newly adopted home. For New Yorkers and visitors confronted by congested street life, such prints offered a way to understand the larger environment, an important means of reading the commercial and consumer activities of the ever-expanding city, a task that was increasingly difficult as buildings grew taller and signs of commercial establishments assaulted the eye, as historian David Henkin suggests. In Hornor’s upper-floor view of Broadway and Canal Street, signs dot the left, right, and center sections of the print, offering the viewer a broad vision of the commercial character of this intersection. There is John Wright’s hat shop, a wig store, and a store offering upholstery, in addition to Morison’s “Hygeian” medicines in the British College of Medicine building.

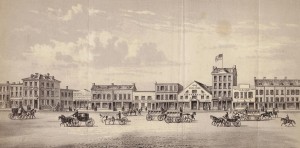

Fig. 2 George Hayward. “View of Broadway, N.Y. between Howard & Grand Streets, 1840,” 1861. Lithograph, for D. T. Valentine, Manual of the Corporation of the City of New-York (New York, 1861). Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

+Another view, a visual street directory by George Hayward of Broadway between Howard and Grand Streets in 1840 (fig. 2), offers an elevation view that serves almost as a map, depicting both the scale and the height of the buildings on this block as it presents a straightforward perspective of the street life and signs that defined this commercial corridor. Although neither Hornor nor Hayward intended to map the city in a literal sense, both attempted to promote a view of order and civility at street level, advising the image’s consumer, likely a New Yorker, on appropriate modes of social conduct.

Clearly Hornor attempted to convey a sense of order at this intersection, but there is no escaping the fact that it was the people rather than the buildings that gave the place its energy. He tried to categorize the urban types that populated Broadway on a busy shopping day by reducing them to a recognizable visual vocabulary, a reflection of the taste-making classes’ desire to read urban chaos in succinct, civilized parts. As New York City historian David Scobey suggests, “Bourgeois New Yorkers . . . envisioned a streetscape that would balance dynamism and refinement. It would retain the energy and kaleidoscopic diversity of Manhattan’s actual street life, but purge it of its predatory individualism and barbarous class disorders. Like the imagined city of urban sketches, it would recompose the streets into a tableau of civilization.” Hornor’s image offers a classification of the urban hierarchic order, real or imagined, through the depiction of dress and behavior in a motley yet legible fashion.

Fig. 3 J. R. Hutchinson, after William J. Bennett.Broadway from the Bowling Green, 1828, 1828. Hand-colored etching. Eno Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

+On the sidewalks on both sides of the street, genteel ladies in fine dress promenade up and down the block, conveying a sense of refinement in a city of arriviste fortunes, as historian Gloria Deák has noted. This “see-and-be-seen” attitude helped to assert a distinctly Europeanized version of New York society, as in William J. Bennett’s view of Broadway from Bowling Green of 1828 (fig. 3). Bennett’s view, made nearly a decade earlier than Hornor’s, exemplifies a relatively old-fashioned version of the bourgeois street promenading that appears in Hornor’s image. But unlike Bennett, Hornor includes a broader range of the people who made up the urban panorama. Workmen line the streets, some lifting heavy wooden planks, others selling boots and other goods. At the right, two African-American men are engaged in some form of manual labor. Horse-drawn wagons and omnibuses move down Canal Street and up Broadway, reflecting the intersection’s busy commercial purpose. The colorful view extends into the shop windows, where goods are for sale, as at John Wright’s establishment on the right side of the image. In the second-floor window, the appearance of a seamstress suggests that manufacturing took place in this building. In short, Hornor attempts to explain the energetic atmosphere of the commercial hub by grouping the urban types in distinct vignettes and setting them against civilized Broadway shop life.

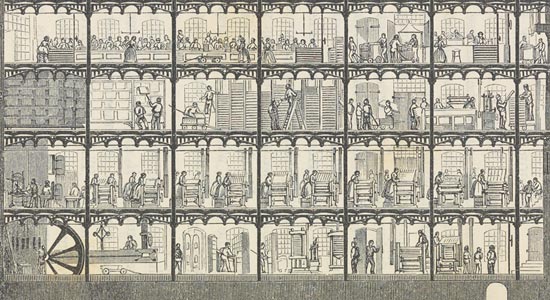

Fig. 4 Thomas Hornor. Unfinished bird’s-eye view of Lower New York, ca. 1837. Pen and wash on paper. I. N. Phelps Stokes Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

+“Downtown design . . . made a spectacle of capital,” David Scobey contends. “Part of what defined a metropolis, after all, was its capacity to theatricalize the forms of its power. In Europe, that power was mainly political and military . . . In New York, the forms of power were primarily commercial.” Prints like those produced by Hornor and Hayward indicated the ways in which the “spectacle of capital” transformed the city. The year after Hornor completed his view of Broadway and Canal, he set about documenting an expansive view of the city’s continued northward expansion. His unfinished bird’s-eye view of lower New York looking north (fig. 4), an effort to capture the sheer scale and development of the Empire City, was as unsuccessful as his Colosseum project had been in London. Hornor’s idealized, seemingly omniscient view of the downtown area looking north ineffectively scales the figures in the foreground with the surrounding buildings. Unlike his view of Broadway and Canal, which presents a rational expression of the grid, this image reflects a struggle to map the commercial city’s scale and grandeur. “It is the work of an artist no longer in his prime,” Hyde suggests. We don’t know if this image remained unfinished because he ran out of either funds or ideas. This is Hornor’s only other known work in New York; he died a pauper a few years later, in 1844.

With his depiction of Broadway and Canal, Thomas Hornor conveyed a sense of the growing commercial city’s fascination with reading itself through print culture. This unique image can be interpreted as a means of understanding the city through signs and commerce and of classifying urban spectacle as a sequence of distinct types and behaviors. In a sense, New York’s mercantile development and, by extension, its power were the result of views like this one that presented a positive image of the emerging commercial city.