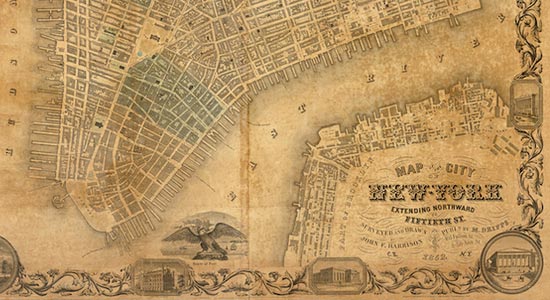

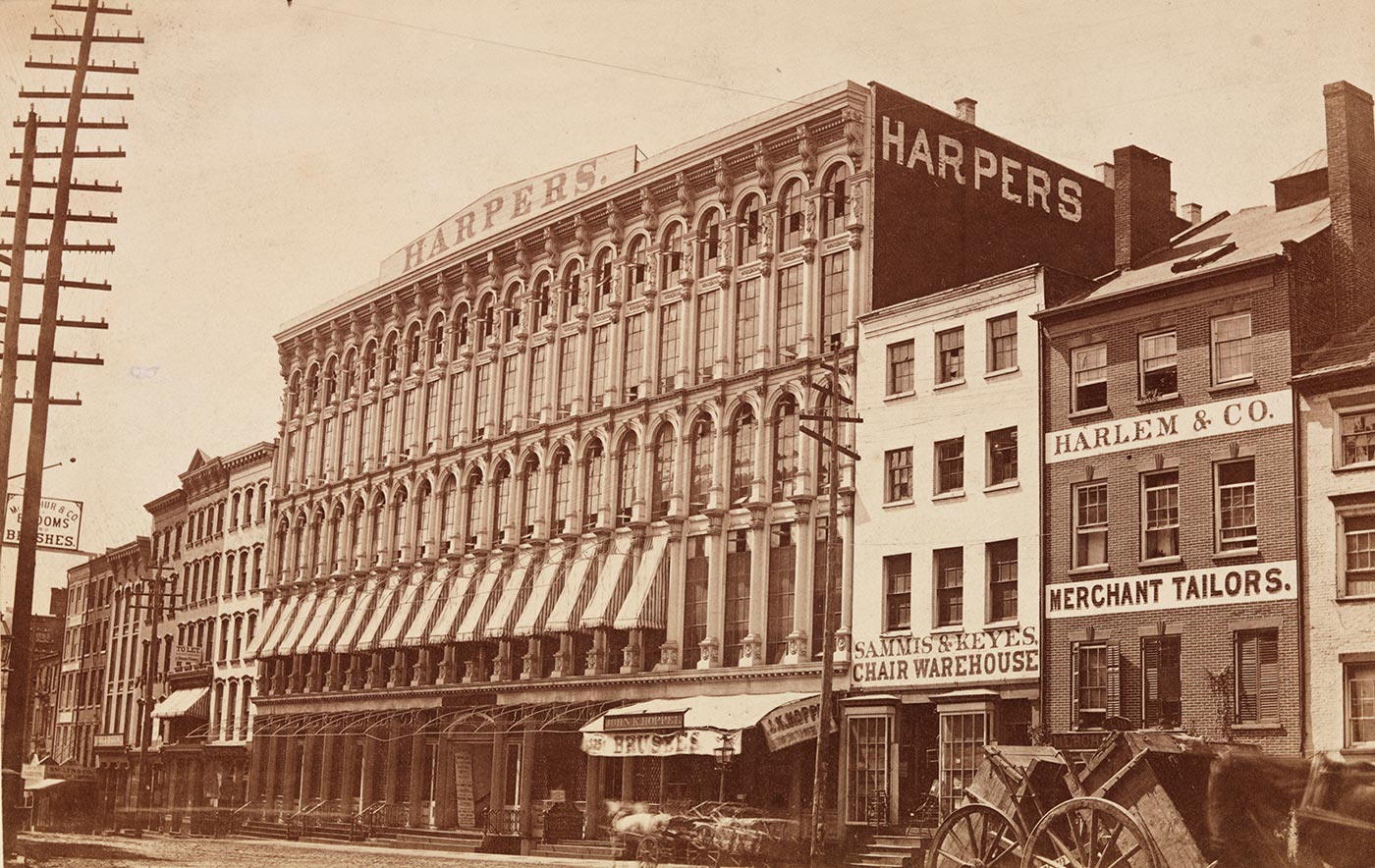

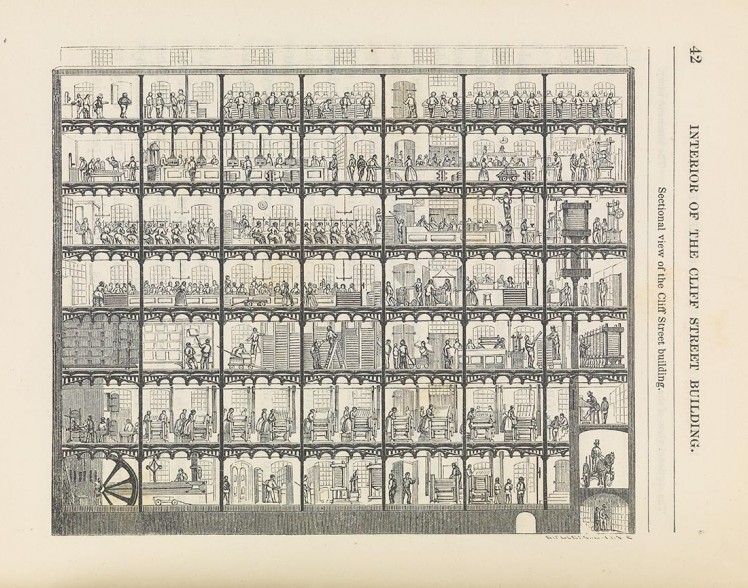

Fig. 1 331 Pearl Street (with Harper & Brothers Building, designed by James Bogardus with John B. Corlies, 1854), ca. 1870. Albumen print. Museum of the City of New York, X2010.11.2987.

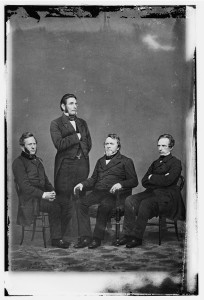

In December 1865, a glorious thirty-one-page article entitled “Making the Magazine” appeared in print in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. It described in detail how the impressive list of publications from the firm of Harper & Brothers was produced. Although readers may not have been familiar with how the magazine was printed and assembled, the firm of Harper & Brothers itself needed no introduction, having become one of the most significant and recognizable publishing enterprises in the country. By midcentury, the company had already become a testament to the entrepreneurial ingenuity of the brothers James, John, Joseph Wesley, and Fletcher (fig. 2). They produced numerous publications for a vast national readership and utilized the latest technologies both in and outside their New York premises, from the rapid printing press to the new and innovative cast-iron headquarters from which they worked. Indeed, no New York publisher experienced the continual success that Harper & Brothers enjoyed during the second half of the nineteenth century.

Fig. 2 Attributed to Mathew Brady. Fletcher, James, John, and Joseph Harper, ca. 1855–65. Collodion type, wet plate. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Brady-Handy Collection.

+The brothers James and John established the firm in 1817 as a small printing venture, but the company quickly expanded, producing not only books but also the most widely distributed American periodicals of the nineteenth century. By the mid-1820s, John Wesley and Fletcher Harper had bought partnerships. After experiencing success in publishing series of books, even during the economic crisis of the late 1830s, the brothers launched their first periodical, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, in 1850. In six months’ time, the magazine’s distribution grew quickly to more than 110,000 copies. Nevertheless, arguably their most important contributions, including the periodical Harper’s Weekly, were still to come, paradoxically in the wake of disaster. In December 1853, when fire engulfed the Harper & Brothers premises at 329–331 Pearl Street, it must have been difficult to envision the future of the company. The New York Times estimated the destruction at over one million dollars—the figure was actually even higher—but the paper reported optimistically that “[p]robably there is not another firm in the United States which combines within itself more business energy, enterprise, and efficiency, than that of these four brothers; and severe as is the disaster which has fallen upon them, the lapse of a year, we are confident, will see them again in the full tide of an enormous business.”

The following year, 1854, the engineer and architect James Bogardus, along with the architect John B. Corlies, erected for the publishing firm a pair of fireproof iron-and-glass buildings connected by a series of iron corridors at Pearl and Cliff Streets (fig. 1). Bogardus had patented his revolutionary method for cast-iron building in 1850, and although the Harper buildings were demolished in 1925, the structure remains an icon of ingenuity in architecture and engineering. In 1982 the artist Richard Haas commemorated Bogardus’s structure in a mural in the New York Public Library’s DeWitt Palace Periodicals Room as one of the most significant buildings housing New York’s important publishers.

It was Bogardus’s “completely fire-proof” buildings that author Jacob Abbott chose to highlight in the popular 1855 book The Harper Establishment; or, How the Story Books Are Made, an account of the construction of the new premises, its structural and mechanical innovations, and the state-of-the-art machinery located within it. The complex, which covered ten city lots, would have made for an impressive show to passersby. The main building at 331 Pearl Street, adjacent to what was then Franklin Square, bore a completely iron façade; it housed the headquarters and offices of the brothers, space for artists and writers, and floors devoted to publication storage and shipment, and the Cliff Street structure contained every facet of the printing process and the factory’s labor force.

Though known for his children’s books, Abbott “made no attempt to bring . . . down to the capacity of children” his description of the factory and its workings, and he wrote that the book could “only be appreciated by minds that have attained to some degree of maturity, and are accustomed to habits of careful and patient thought.” Indeed, it was from this book that the author of the 1865 article “Making the Machine” drew the majority of its content, which included many complicated and lengthy descriptions of recently patented industrial printing processes. The article even reused the 1855 engravings produced by Abbott’s associate, the German-born illustrator Carl Emil Doepler.

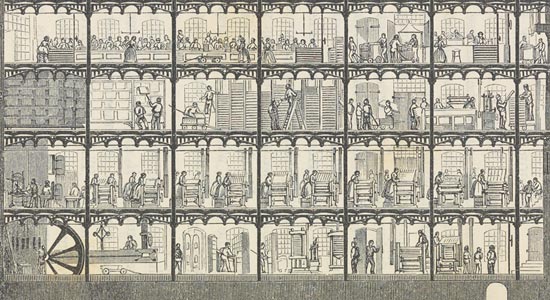

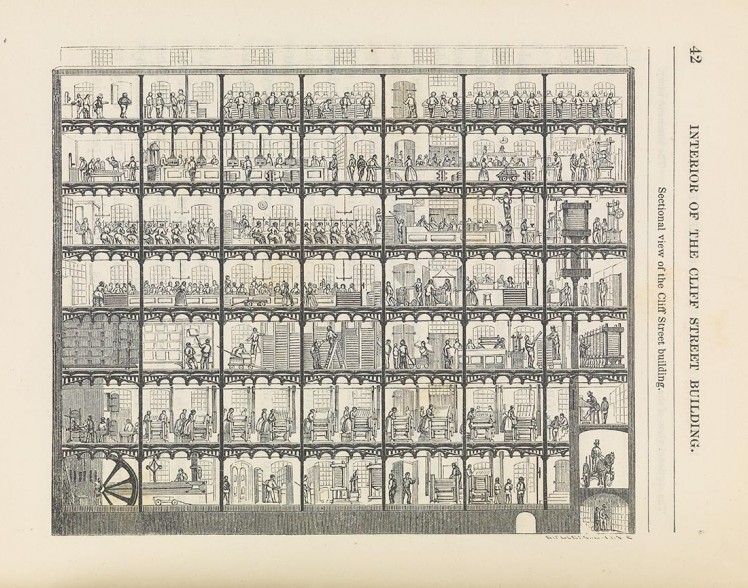

Fig. 3 Carl Emil Doepler. “Sectional View of the Cliff Street Building” (Harper & Brothers Building), 1855. From Jacob Abbott, The Harper Establishment; or, How the Story Books Dre Made (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1855). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Joseph B. Davis, 1942 (42.105.22).

+Abbott’s book gave Harper & Brothers an opportunity to present to readers an account of the firm’s innovative factory production at a time when the public was starting to take more than a passing interest in burgeoning industrial and technological innovations. As historian Vanessa Meikle Schulman has argued, the medium of print, specifically engraving, could combine reality and artistic imagination to craft an image that was in some ways even more revealing of truth. An engraving in the book depicting a cutaway of the Cliff Street building is one such example where the artist took the liberty to give readers a view into the structure that was physically impossible but singularly revealing of the building and the industry that took place on each of its seven floors (fig. 3). Bogardus’s novel bowstring girders, the arched beams bearing the weight of every floor’s columns, are visible at the top of each floor and were unique in their use as both structural and decorative elements.

Although somewhat idealized, Doepler’s engraving depicts the factory’s hectic interior, from the “great composing-room” on the top floor, where compositors are seen setting type for books and periodicals, to the many presses on the first floor above the basement, the paper drying racks on the second floor, and finally the folding, sewing, and book-finishing and binding machines. The cross-sectional image also hints at the company’s division of labor. The dozens of mechanical apparatuses represented give a sense of just how innovative and paradigmatic the business was by midcentury, housing the latest rapid printing presses and commanding an enormous workforce. As early as 1853, Harper & Brothers had introduced new methods of printing by using electrotyping in order to meet increasing demand. Although it is meant to reinforce Abbott’s accompanying text on the firm’s machinations, the engraving, as well as the individual illustrations of each floor, like that of the steam-powered press visible on the first floor above the basement, could indeed stand alone as a visual explication of the Harper firm’s publishing process (fig. 4). Women would feed the paper to be printed through the “power-press,” called the “Adams press” after its inventor. The company installed twenty-eight Adams presses in the new Cliff Street building in 1855. The complicated belts of the press even begin to blend in with and morph into the architectural surroundings, like the iron Corinthian columns designed by James L. Jackson, which were visible on every floor and are schematically represented in the cutaway view.

Fig. 4 Carl Emil Doepler. “The Power-Press,” 1855. From Jacob Abbott, The Harper Establishment; or, How the Story Books Are Made (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1855). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Joseph B. Davis, 1942 (42.105.22).

+It was already clear that Harper & Brothers, geniuses in matters of publicity since the 1840s, knew they were onto something big when, two years after the publication of Abbott’s book in 1857, the first issue of Harper’s Weekly was published. In the inaugural issue, one writer declared, “Neither labor nor expense will be spared to make it the best Family Newspaper in the World.” Here the author was likely making reference to the newspaper’s position as being both influenced by and in competition with the prominent London Illustrated News. Harper’s Weekly’s readership less than a decade later hints at the firm’s interest in circulating so widely: by 1865, it sold an average of 100,000 issues per week, with some single issues selling as many as 300,000 units. A single issue may have been read by as many as five individuals, as publishers posited, making the newspaper’s weekly readership as many as half a million. A writer for the North American Review reported on the newspaper’s immense national importance in 1865: “Its vast circulation, deservedly secured and maintained by the excellence and variety of its illustrations of the scenes and events of the war, as well as by the spirit and tone of its editorials, has carried it far and wide. It has been read in city parlors, in the log hut of the pioneer, by every camp-fire of our armies, in the wards of our hospitals, in the trenches before St. Petersburg, and in the ruins of Charleston; and wherever it has gone, it has kindled the warmer glow of patriotism . . . and it has done its full part in the furtherance of the great cause of the Union, Freedom and the Law.”

Harper’s interest in portraying their ever-growing establishment and factory was thus well known at the time, but the firm shared little actual information regarding their workforce. Although visible in Abbott’s book, as well as in A. H. Guernsey’s 1865 article in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, workers were still portrayed as secondary, and anonymous, in comparison to the new technologies that the company championed. With the mechanization of the printing process and the move to large-scale factory production, publishers like Harper & Brothers hired less skilled young workers for lower pay instead of the highly trained printers of yore. Abbott noted the three hundred women who worked printing and folding presses and finishing books, but he was more keen to describe their “attractive appearance and lady-like manners” than their abilities. That perhaps comes as no surprise, given that their salaries were, along with young boys, as little as five dollars a week. This stands in dramatic contrast to the salaries of those who worked in the Pearl Street offices, such as the head of the art department, Charles Parson, who made over sixty dollars a week, and Winslow Homer, whose salary began at fifty dollars in 1863. The weekly salary of political cartoonist Thomas Nast was still higher, at over 170 dollars.

Such disparities in pay were certainly not unheard of in the publishing industry, but they remained unknown to the readers of Harper’s publications. Despite this, or perhaps because of it, Harper’s Weekly—and indeed, the whole of the Harper establishment—became an important part of the city’s cultural landscape for readers and laborers alike. The firm’s mid-century success, with the rebuilding of their factories in 1854 and the publication of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine and Harper’s Weekly, was due in large part to the brothers’ business acumen and ability to build such an empire. By the end of the 1870s, the last surviving brother, James Fletcher, died, and shortly thereafter the company began to face financial difficulties. In 1916, just before the United States entered World War I, Harper’s Weekly was subsumed into the newspaper The Independent. Three years earlier, Harper’s Bazar (now Harper’s Bazaar), the ladies’ magazine begun in 1867, was sold to William Randolph Hearst, and by the 1920s hardship forced Harper to sell the Pearl Street location. The firm’s legacy continues today not only through Harper Collins, but also through the publication of Harper’s Magazine and Harper’s Bazaar. Although neither of the company’s most prominent efforts of the nineteenth century survives today—the Bogardus buildings were demolished in 1925 and Harper’s Weekly had ceased publication nine years earlier—Harper & Brothers stood as a publishing colossus amidst New York City’s major industrial entrepreneurs.