New York City had firmly established itself as the cabinetmaking capital of America by about 1825, during the heyday of New York’s most famous furniture maker, Duncan Phyfe, and remained a prominent producer as well as a sales center for furniture until at least 1875. From the finest parlor furnishings sold in upscale galleries on Broadway to the “dingy . . . old furniture establishments” selling on the Lower East Side near Five Points, New York became as much a site of furniture manufacture as of the production of prints, photography, and books. By the middle of the century, there was an increased demand for furniture to decorate the typical American home, in particular the parlor, thanks to the rise in middle-class ambitions to achieve gentility. The parlor exemplified the meeting place of commercial goods and metropolitan life, middle-class identity, domesticity, and comfort. The parlor and the furniture trade have received much scholarly attention for their cultural and social significance. Steady progress in the production and trade of household furnishings made the domestic parlor into an attainable space across the social classes, and the affordability of parlor furniture produced in New York owed much to the city’s labor population and its industrial entrepreneurs.

Fig. 1 “Brady’s New Daguerreotype Saloon, New York,” 1853. From Illustrated News, June 11, 1853. The Daguerrian Society.

+Inhabitants and visitors alike were encouraged to draw decorating inspiration less from those growing factories and shops than from the city’s public parlors, what Katherine Grier has called “commercial parlors,” in hotels such as the Astor House (see Kelly-Bowditch, “The Paprill Hill View”) to photographic galleries (see McKee, “Mathew Brady and the Daguerreotype Portrait”). Brady’s gallery functioned as one such space, where consumers could enact the social codes that would then extend to the domestic parlor but could also glean a physical ideal of parlor decoration (fig. 1). The studio of daguerreotypist M. M. Lawrence contained rosewood furnishings and a marble-top center table, similar to the unattributed rosewood table combining rococo volutes and cabriolet, Jacobean turning, and neoclassical lion’s paw feet in figure 2. A rococo revival rosewood side chair of exaggerated size, form, and carving, was probably inspired by the luxury furniture of the firms whose showrooms lined Broadway south of City Hall, (fig. 3). It resembles the side chair in which the opera singer Jenny Lind sits in a three-quarter-length portrait taken at Brady’s studio (fig. 4).

Fig. 2 Center table with marble top, 1850–70. Rosewood, oak, marble. Collection of The New-York Historical Society, Gift of Mary Clinton Brown, 1940.286ab.

+By mid-century, Broadway had become the main thoroughfare for consumers interested in seeing the showrooms of high-end cabinetmakers, including the émigrés John Henry Belter, Gustave Herter, Julius Dessoir, and Alexandre Roux, to name only a few. The success of these makers of fine furniture has often placed them at the center of recent discussions of the trade. For instance, by 1860 Gustave Herter’s firm had an inventory of tens of thousands of feet of walnut, oak, rosewood, and mahogany and employed one hundred men. A few years earlier, Belter built a factory far uptown on Seventy-sixth Street to accommodate his growing business, but he maintained a showroom presence at 552 Broadway, close to Tiffany and Company.

Fig. 3 Side chair, 1850–60. Rosewood, oak, textile. Collection of The New-York Historical Society, Gift of Mrs. F. Leighton Meserve, 1979.100.

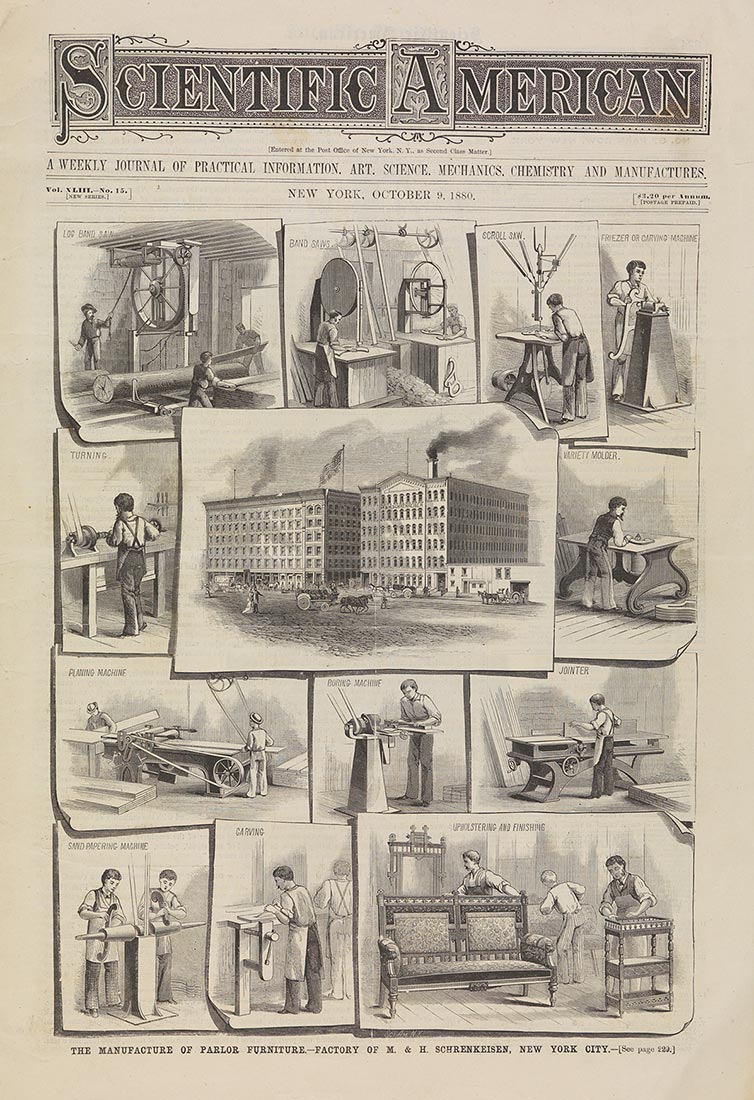

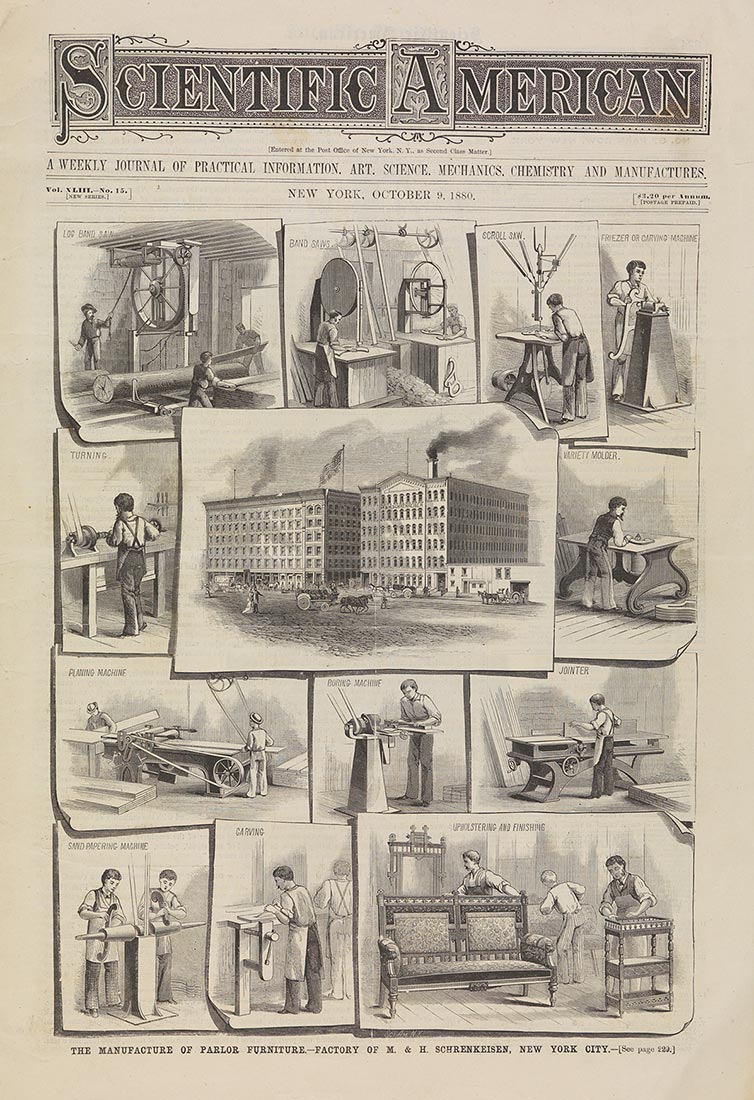

+Broadway’s luxury furniture may have been out of reach for the average middle-class consumer, but for those unable to afford a matching set, as was the vogue, a single striking piece of furniture could stand in for an entire parlor suite. Cheap furnishings were available in abundance on the Lower East Side, in an area then called Kleindeutschland (Little Germany), or what the cabinetmaker Ernst Hagen later described as the “Colony of German mechanics.” Little Germany’s most successful middle-class manufacturers, such as the German-born brothers M. & F. Schrenkeisen, who specialized in parlor furniture, catered to working and middle classes, offering “the lowest-priced [parlor] suites the firm ever manufactured.”

Fig. 4 Mathew Brady, attributed to operators John Carl Frederick Polycarpus Von Schneldau or Luther Boswell. Jenny Lind, 1850. Whole plate gold-tone daguerreotype. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

+Little Germany’s factories and showrooms were often located together in small single-story establishments, and they accounted for most of New York’s furniture production. The neighborhood stretched over four wards and contained the area east of the Bowery, north of Division Street, and south of Fourteenth Street. The mid-century furniture trade’s vast expansion was the result in large part of the city’s growing immigrant population, much of which was located in Little Germany. Of the estimated three thousand cabinetmakers who called New York home by the early 1850s, two-thirds were Germans, a population that had grown rapidly from the early decades of the century. This growth was directly linked to the increased demand for goods, and New York’s furniture makers, in particular those working at the lower end of the market, sold their wares not only to local furniture stores but also to the South, the West Coast, and even the West Indies, as Ernst Hagen recounted. The burgeoning eastern metropolis stood singularly capable of churning out goods that could supply an entire nation.

Nevertheless, the furniture trade’s economic boom came at the expense of those immigrant laborers. Changes in workers’ rights and decreased wages became the norm as the number of furniture workers increased. Other means of allaying costs included the outsourcing of work to offsite turners and sawyers and importing hardware from the continent. Despite the onset of machine production and developments in the way of hand- and foot-pedaled machinery and steam power by 1860, manpower remained one of the most important factors in furniture production as late as the 1870s. Many businesses adopted new tools slowly, and even in an age punctuated by great technological improvements, mass production continued to be driven by immigrants who were willing to work for little and who had limited access to mechanized tools and the like.

Fig. 5 “The Manufacture of Parlor Furniture—Factory of M. & H. Schrenkeisen, New York City.” Cover of Scientific American, 43, no. 5 (October 9, 1880). Collection of David Jaffee. Photographer: Bruce White.

+The cover of an 1880 issue of Scientific American depicted the activities at Schrenkeisen’s successful Lower East Side establishment (fig. 5). The six-story factory, situated at 23–29 Elizabeth Street, is depicted, with dark clouds billowing from its pipes, at the center of a collage that illustrates the bustling industry taking place inside, albeit in an idealized, uncrowded, and clean environment. The accompanying article stresses the care that Schrenkeisen craftsmen lavished on singular pieces, echoing the cover’s romantic notions of the attentive craftsmen. However, the image glosses over the division of labor that had been in in place since the middle of the century. Unstable wages plagued the industry, dropping low in the depressions of the 1840s and 1850s and rising again only after a great struggle by unions in the last quarter of the century. The Germans led the labor movement in New York, and the cabinetmakers played a major role in this effort for the next several decades. A New York Times article reported on one such incident, citing Schrenkeisen’s practices:

Another strike among cabinet-makers is now well under way, and most of the large furniture houses are affected by it. The strike is confined to wood-workers, who refuse to work more than 56 working hours per week, instead of the 60 hours called for by the manufacturers. The whole trouble originated in the factory of Messrs. M. & H. Schrenkeisen. Made bold by the success of Henry Hermann’s men last Spring, the cabinet-makers in the Schrenkeisen factory have made several demands for higher wages, and to these demands the firm have acceded. Then came, three weeks ago, a demand for 56 hours’ working time per week, without a reduction in wages. This demand was also granted by the firm. A week later the firm discharged six men from its factory, among them being some of the leaders in the various movements for less work and more pay.

The average middle-class consumer may never have considered the many immigrant hands that produced their parlor furniture, let alone the struggles faced by workers. Purchasers of luxury furnishings along Broadway would have been even further removed from such reflections. Nonetheless, the factories on the Lower East Side and the importance of the immigrant worker’s story in forming New York’s furniture manufacturing industry cannot be understated. These furnishings, as material remains, can also offer a glimpse into the making of an entire industry, and the subsequent growth of a great manufacturing city. The meteoric rise in the manufacture of parlor furniture is, alongside its many commercial arenas, part of what represents New York’s rapid metropolitan transformation in the nineteenth century.