John Bachmann, a German-speaking Swiss printmaker, arrived in New York in 1848, having fled the upheavals of revolution in Europe. Bachmann had produced a number of low-altitude views in Paris and Switzerland, including images of the Place de la Concorde and steeple views of Swiss towns in the early 1840s. Bachmann’s prints exemplify an American reinterpretation of the European bird’s-eye view at a moment when American cities, particularly New York, were defining their modern civic identity. In their pastoralism, early nineteenth-century American pictorial views, made primarily in aquatint, served to distance their viewers from the industrialized city and its dangers. Lithographic bird’s-eye views, which emerged in the 1840s, instead celebrated the evolving industrial city and its modern features. Two-thirds of Bachmann’s lithographs were of New York City, recording the technological as well as conceptual shift in the representation of American metropolitan life.

Fig. 1 John Bachmann. Union Square, New-York, 1849. Hand-colored lithograph by Sarony & Major, published by Williams & Stevens, New York. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Susan Dwight Bliss, 1966 (67.630.142).

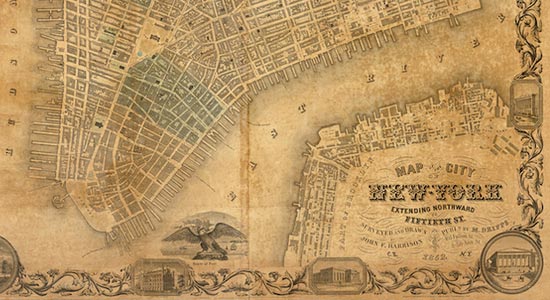

+Union Square, New-York, Bachmann’s first American bird’s-eye view, as well as the first full-scale bird’s-eye image of the city, was made in 1849 (fig. 1). Earlier views of New York were drawn from the bluffs of Brooklyn Heights or other lofty perches, such as steeples, or from the harbor to demonstrate their accurate depiction of nature. This conceit is seen in John William Hills’s 1836 View of New York from Brooklyn Heights with its birds on the rooftop in the foreground. Bachmann similarly proclaimed his images to be “Drawn from Nature on Stone,” an inscription he included in the left corner of the frame of his prints. Although bird’s-eye views appear to be captured from above the city, they were mathematically compiled on a map or a grid of the city based on hundreds of sketches made on the ground.

The perspective of Union Square, New-York looks south from Union Square Park, with its tip pointing toward a distant horizon. Ships dot the rivers and the docks burst with activity. More than the bustle of the port, Bachmann has prominently featured the oval-shaped Union Square Park in the foreground, which had opened in 1839. Fashionable dwellings eventually circled the perimeter of this new residential district circle. The gushing fountain was erected to celebrate the opening of the Croton Aqueduct, which brought sufficient clean water to the quickly expanding population. One journalist remarked that this fountain, and its companion at City Hall Park, “are said to be unsurpassed by any others of the kind in the world, and are therefore flattering evidences of the skill of American mechanics.” The development of public works projects such the Croton Aqueduct transformed city life and the American public’s conception of civic government’s role in it. In the print, Bachmann frames and presents multiple stories of the expanding city that were transforming it into a rival of Europe: a distant world of trade coming into a bustling port, the orderly rows of buildings and fashionable dwellings between busy streets, and the marvels of American technological skill.

Fig. 2 John Bachmann. Bird’s Eye View of Greenwood Cemetery, New York, 1852. Lithograph with tint stone. Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

+Bachmann’s prints often framed the city’s innovative new spaces, such as Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, which he depicted in 1852 (fig. 2). The cemetery was founded in 1838, modeled on the European cemeteries Père Lachaise and Campos Santos, as well as Boston’s Mount Auburn. New York’s enormous population growth between 1820 and 1860 created a real estate crisis, not only for the living but also the dead, since many former churchyards were destroyed by the opening of new streets. As diarist George Templeton Strong wrote, “For in this city of all cities some place is needed where a man may lay down to his last nap without the anticipation of being turned out of his bed in the course of a year or so to make way for a street or a big store or something of that kind.” In the face of rapid urban development, many political and cultural leaders believed that nature served as a powerful counterbalance to the ills of the city. Years before Central Park opened, Green-Wood reconciled the troubling divide between country and city life, offering not just a final resting place, but also a fashionable venue for promenading and carriage rides. Its romantic landscape offered escape from the city. Bachman’s image captures this lush, green landscape, dotted with trees, rolling hills, and curving roads, which contrast with the constructed linearity of his earlier view of New York from Union Square. The distant sky and the sea, here still dotted with ships, occupy a much smaller portion of the frame, which allows green to encompass the viewer. The ambling pleasures that Bachmann depicts echo the description composed by Lydia Child: “no guest has been courteously entertained until he has been driven through its winding avenues, and looked down upon the bay and the city from its commanding heights.” By adding hand-painting, Bachmann emphasizes the glistening white marble of obelisks, pyramids, and tombs that dot the pastoral landscape. These monuments, like fine objects in the parlor, reinforced a fashionable New Yorker’s identity. The New York Times reported in 1866 that it was as much the ambition of the New Yorker to live on Fifth Avenue and stroll in Central Park as it was to “sleep with his fathers in Green-Wood.” Bachmann would go on to highlight other prominent mid-century civic landmarks, such as the Crystal Palace in 1853 and Central Park in 1865. His prints not only framed the new urban institutions that would define the emerging Empire City but also naturalized them for a broader public.

Fig. 3 John Bachmann. The Empire City, Birdseye View of New York and Environs, 1855. Chromolithograph with hand-coloring, printed by L. W. Schmidt, published by Adam Weingartner. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Edward W. C. Arnold Collection of New York Prints, Maps and Pictures, Bequest of Edward W. C. Arnold, 1954 (54.90.1198).

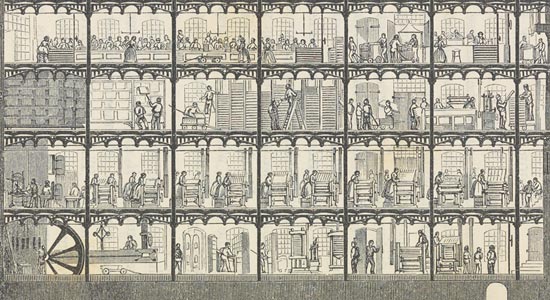

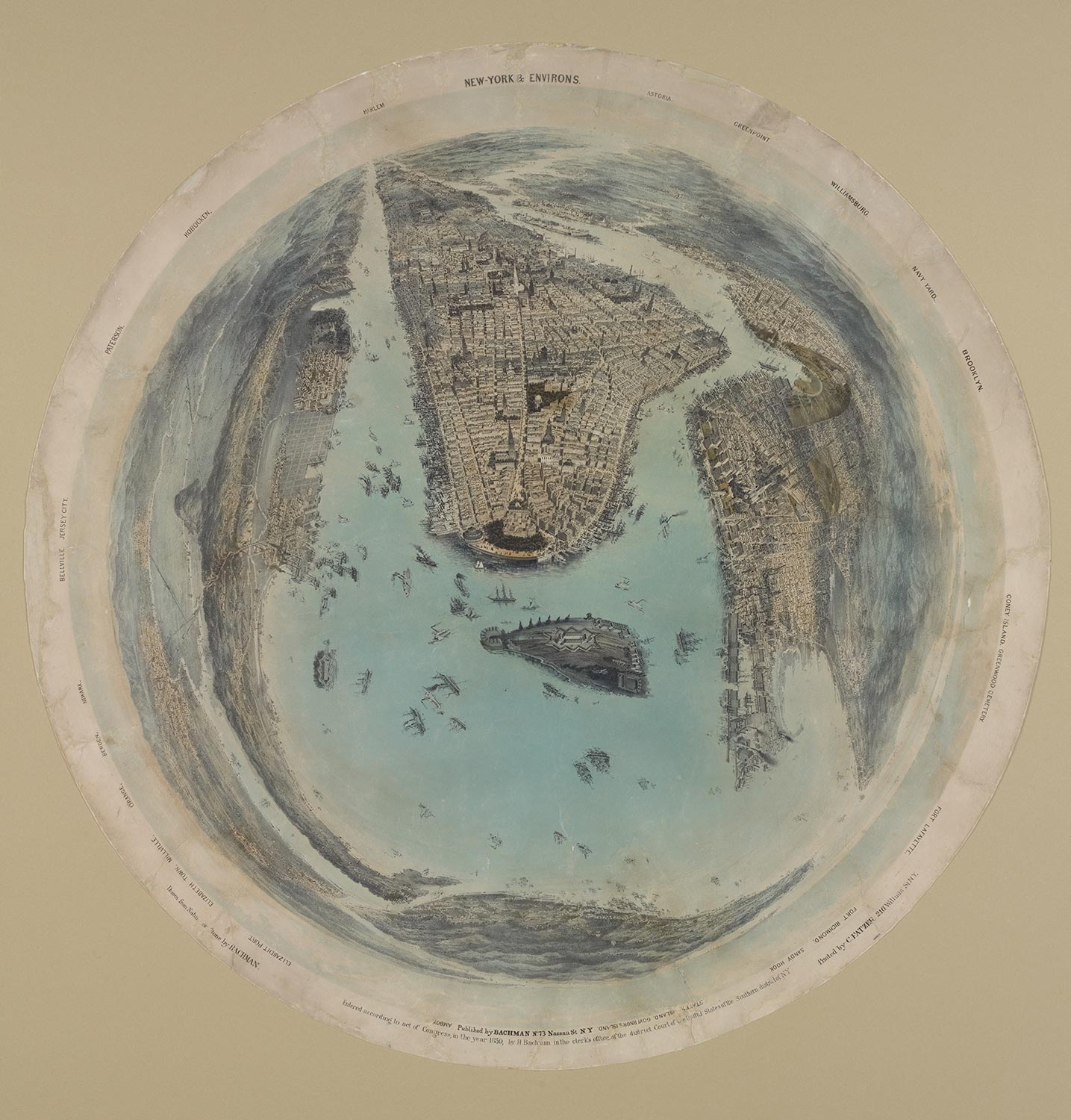

+The Empire City, Birdseye View of New York and Environs shows Bachmann playing with the bird’s-eye view in new ways to produce diverse visual arguments (fig. 3). Bachmann’s prints experiment with depicting urban space to create a sense of security through order while also reinforcing emerging definitions of modernity. In what was becoming an iconic way of depicting the city seen from the southern tip of the Battery, the island of Manhattan stretches out into the horizon progressively erasing the city’s geographic complexity and social divisions. Where once rambling hills and rivers had appeared, steeples peek out of a rich, imagined urban tapestry in the upper reaches of the island. This view of 1855 depicts a much larger and denser city than had ever before appeared in print. Bachmann imaginatively projects a robust urban future for New York. In the foreground, a few institutions, including the Merchant’s Exchange and City Hall, protrude recognizably, but most of the familiar sites from guidebooks and prints are subsumed into this more unified image. Broadway opens wide like a river flowing with horse-drawn carts, omnibuses, and people.

Fig. 4 John Bachmann. New York and Environs, 1859. Hand-colored lithograph. Eno Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

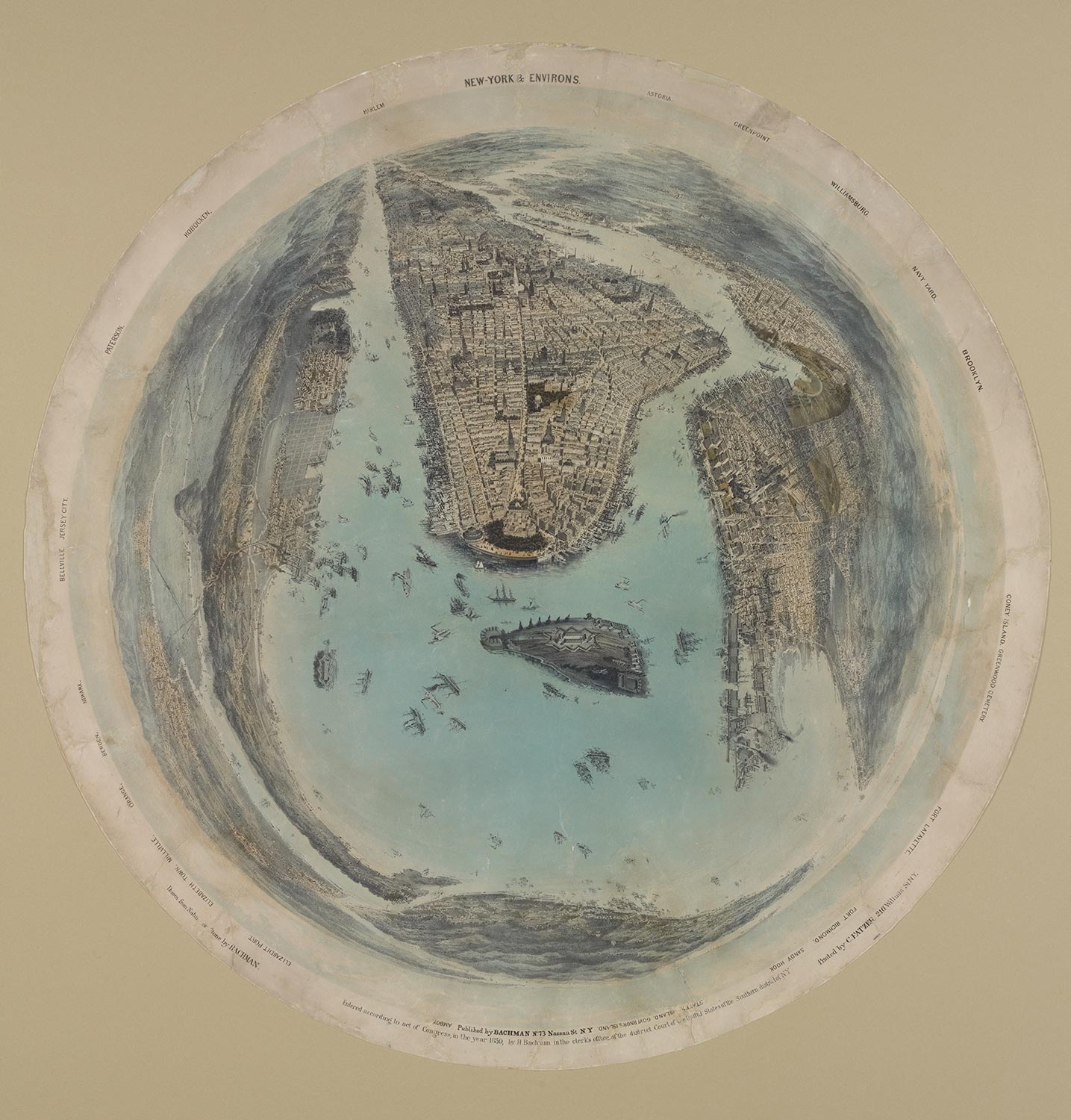

+New York and Environs of 1859 takes a more radical perspective than Bachmann’s previous views in announcing New York’s emerging role (fig. 4). Here New York is viewed from far above the earth, beyond the height of a bird’s flight. Individual buildings and monuments are only small elements that can barely be glimpsed between rows of streets. Looking closely, one can see that Bachmann’s precise rendering still shines through, but here his story is different. The fish-eye distortion of the view makes New York appear at the center of the world, and the addition of blue hand-painting emphasizes this. Although all of Bachmann’s other prints, except for The Empire City, were rectangular images printed inside a colored printed border, New York and Environs is circular, which adds to its globelike appearance. The border is gone, and instead labels circle the perimeter of the image, pointing to twenty-three adjoining regions, including Williamsburg, Green-Wood Cemetery, Jersey City, and Harlem. Bachmann has constructed a visual statement similar to the metropolitan vision asserted in Mrs. Martha J. Lamb and Mrs. Burton Harrison’s 1880 History of the City of New York: “a radius of from twenty to thirty miles from the City Hall has become almost a continuous city, and is virtually New York.” The once insecure and newly American city, soothed by a pastoral landscape, here confidently asserts its place at the center of the world.

Bachmann’s prints graphically depict the evolving visual language, which operates in tandem with the dramatic changes made to the city’s landscape in just two decades. By mid-century, urban city views became the most popular commercially produced type of lithograph, appearing as household decorations or used—as was more likely with Bachmann’s views—for public display in municipal settings, serving decision makers and civic boosters as advertisements of the wonders of urban life. John Bachmann’s prints illustrate an artistic effort to visualize the increasingly unknowable city of New York, which required him to invent new forms of visual argument at a time when the bounded commercial antebellum city was becoming the sprawling metropolis of the postbellum United States.