Stereoviews—three-dimensional images formed through the replication of human binocular vision (see Spofford, “The Scientific ‘Magic’ Behind Stereoviews’ 3-D Realism“)—originated as European imports, but American entrepreneurs quickly recognized their potential as a new dramatic and entertaining form of photography and began producing them stateside. Edward and Henry T. Anthony ran a successful business manufacturing and selling stereocards and stereoscope apparatus, which became well known throughout the United States and across the Atlantic. The brothers began in 1856 with a photographic equipment and supply store at a major commercial intersection on Broadway, but the opening in 1860 of the architecturally grand Stereoscopic Emporium further uptown fully established E. and H. T. Anthony & Company as a notable destination for shoppers. The stereoscopic images mass produced at their New York manufactories circulated across the globe thanks to a variety of successful distribution and marketing methods, including a brick and mortar storefront, catalogue orders, and print advertisements. Anthony & Co.’s “Instantaneous Views,” highly detailed photographs that froze moving subjects with a precision never seen before, quickly became fundamental cultural commodities in nineteenth-century American parlors.

Born and raised in New York City, the Anthonys had strong local ties through their colonial Dutch heritage. The brothers started as amateur daguerreotypists while pursuing careers as civic engineers on the Erie Railroad and Croton Reservoir. Trained under the multitalented entrepreneur Samuel F. B. Morse, who was one of the first Americans to dabble in photography, Edward Anthony used his photographic skills to document the northeastern boundary of the United States during a government-sponsored survey conducted by Professor James Renwick. A subsequent brief stint in portraiture of congressmen in Washington, D.C., led him to pursue the photographic supply trade. By 1848 Edward Anthony and Mathew Brady shared occupancy of 205 Broadway and offered related services. Brady made daguerreotype portraits, while Anthony sold supplies and reproducible engraved versions of his counterpart’s unique images. The business and personal relationship of these two entrepreneurs remained strong even after Anthony moved farther up Broadway.

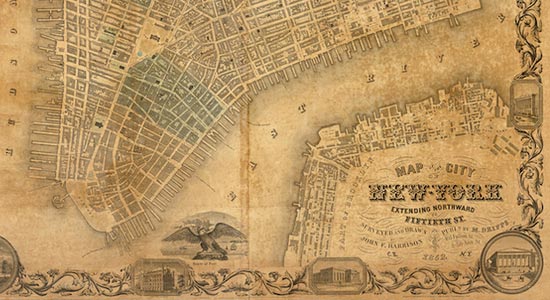

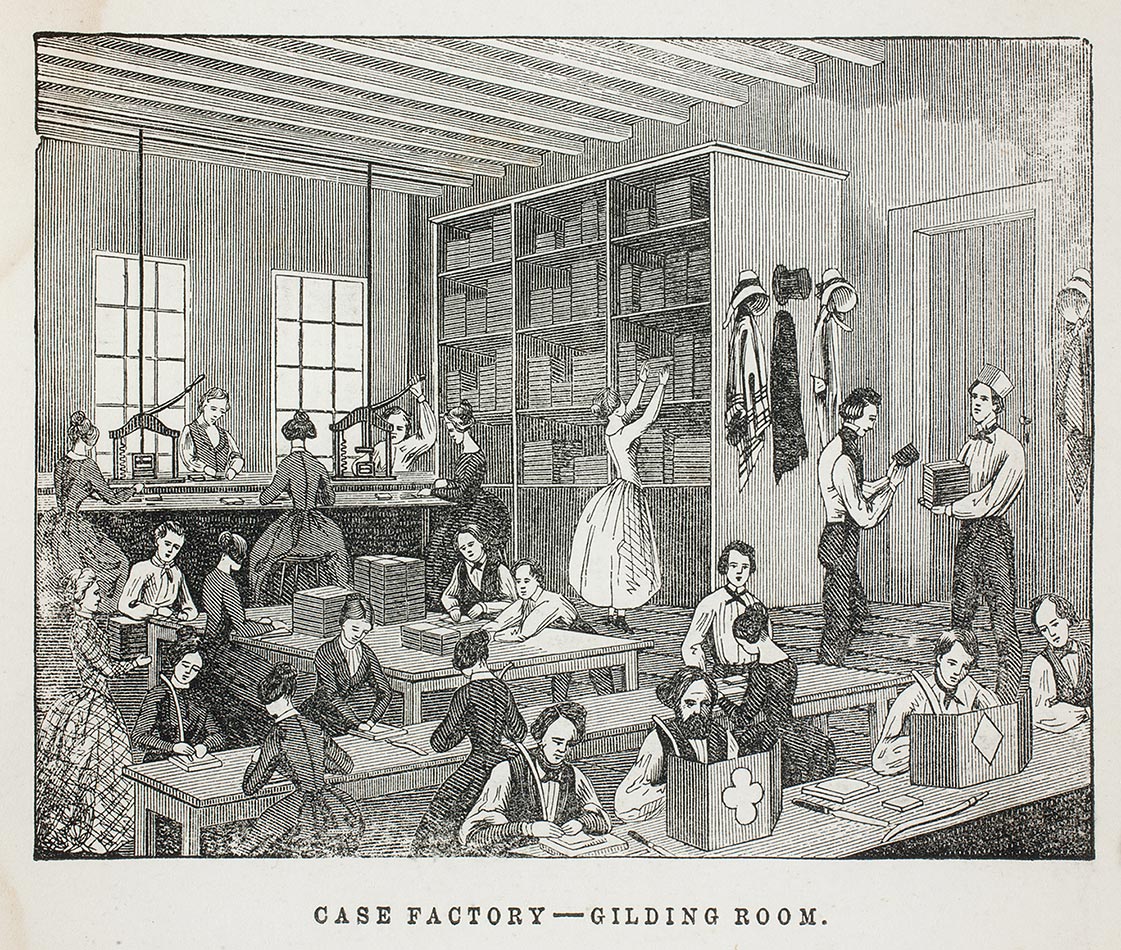

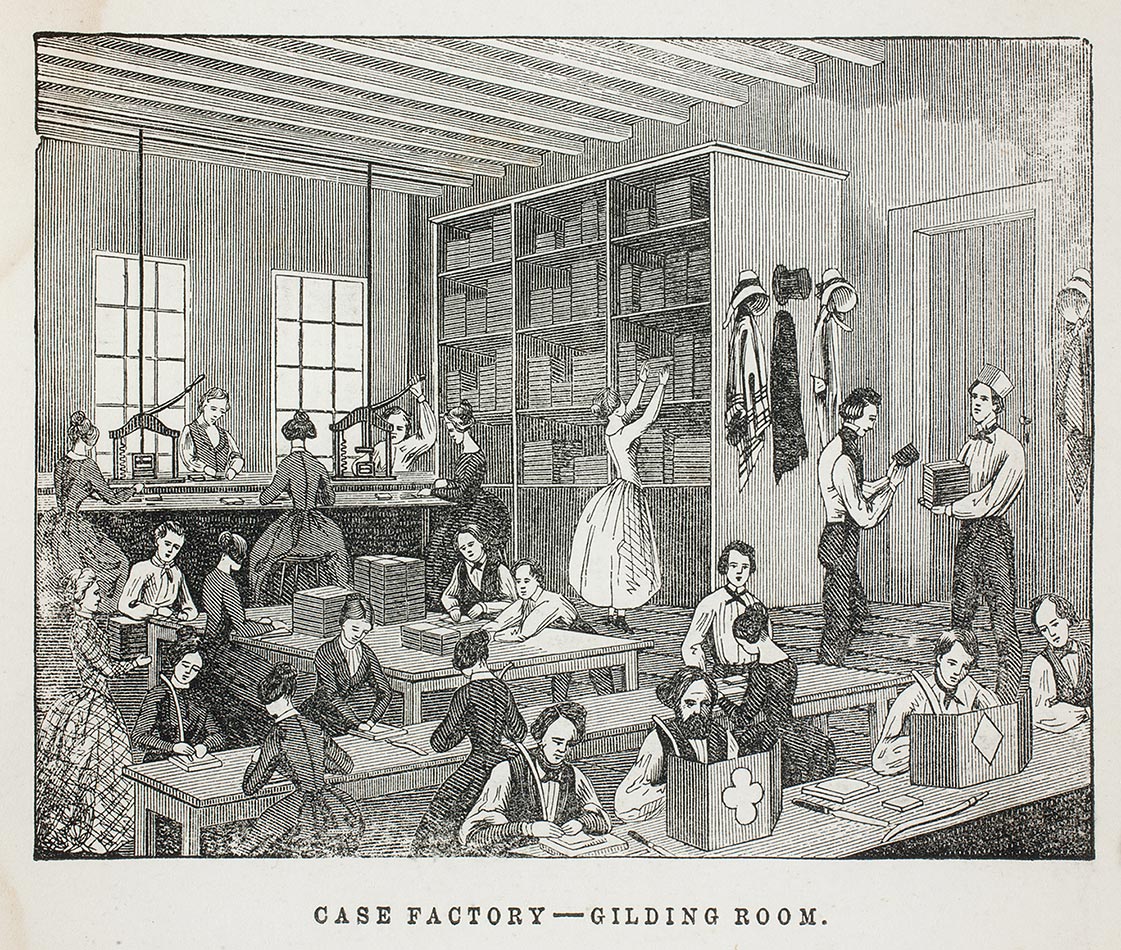

Fig. 1 “Case Factory – Gilding Room.” From Henry Hunt Snelling and Edward Anthony, A dictionary of the photographic art… together with a list of articles of every description employed in its practice (New York: H. H. Snelling, 1854). Courtesy of George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film.

+Edward’s official partnership with Henry in 1852 added his brother’s scientific and business acumen to the company and inspired the two to open a manufacturing facility at 331 Fifth Avenue in the former Harlem Railroad Depot building. Teams of workers spread throughout different departments, completing a variety of steps to produce professional-grade photographic materials and a wide selection of the latest equipment designs (fig. 1). Stereocards required handling by more than fifty people before they reached the retail shelves, and an administrative staff was also required to handle the large number of purchases from catalogues mailed to potential customers. Anthony & Co. hired employees based on their ability to effectively complete specific designated tasks in the assembly process and thus created a diverse staff, including women and some with disabilities, unlike many other contemporary businesses. Henry Anthony also developed custom recipes for producing albumen with heightened photographic sensitivity and for achieving a glossy finish that would not discolor their images, and these innovations made their products stand out from those of competitors. This vertical integration lowered costs, which made their products accessible to a wider number of people, and allowed them to meet rising demand.

Fig. 2 Designed by Oliver Wendell Holmes and Joseph Bates. Stereoscopic viewer (with stereoscopic view), 20th century. Library, Bard Graduate Center. Photographer: Bruce White.

+The popularity of stereocards grew dramatically after the invention of the compact and handheld Bates-Holmes viewer (fig. 2). By 1873 Anthony & Co. offered more than 11,000 stereoviews for purchase, although the total was actually less than that, since some numbers never had actual images assigned. In addition, other pictures were recycled and listed with higher numbers and new titles. It was not uncommon to find a single stereoview photograph appearing over time on multiple cards with differing labels.

Fig. 3 Edward Anthony and Henry T. Anthony. Broadway on a Rainy Day, 1859. Albumen silver prints from glass negatives (stereoscopic views), published by E. & H. T. Anthony, Anthony’s Instantaneous Views, No. 5095. Collection of The New-York Historical Society, PR65.0423.0019.

+Anthony & Co.’s sharp photographs, or “Instantaneous Views,” brought the firm critical acclaim and commercial success. Stereoviews such as Broadway on a Rainy Day (fig. 3) captured the bustling urban scene, including such minute details as the dreary weather and slick sidewalks. Oliver Wendell Holmes describes an Anthony image saying, “But what a wonder it is, this snatch at the central life of a mighty city as it rushed by in all its multitudinous complexity of movement . . . the hurried day’s life of Broadway will have been made up of just such stillness. Motion is as rigid as marble, if you only take a wink’s worth of it at a time.” The enhanced sensitivity of the albumen paper combined with improved camera shutter speed technology, both invented and manufactured in-house, made it possible to document such street activity “stillness.”

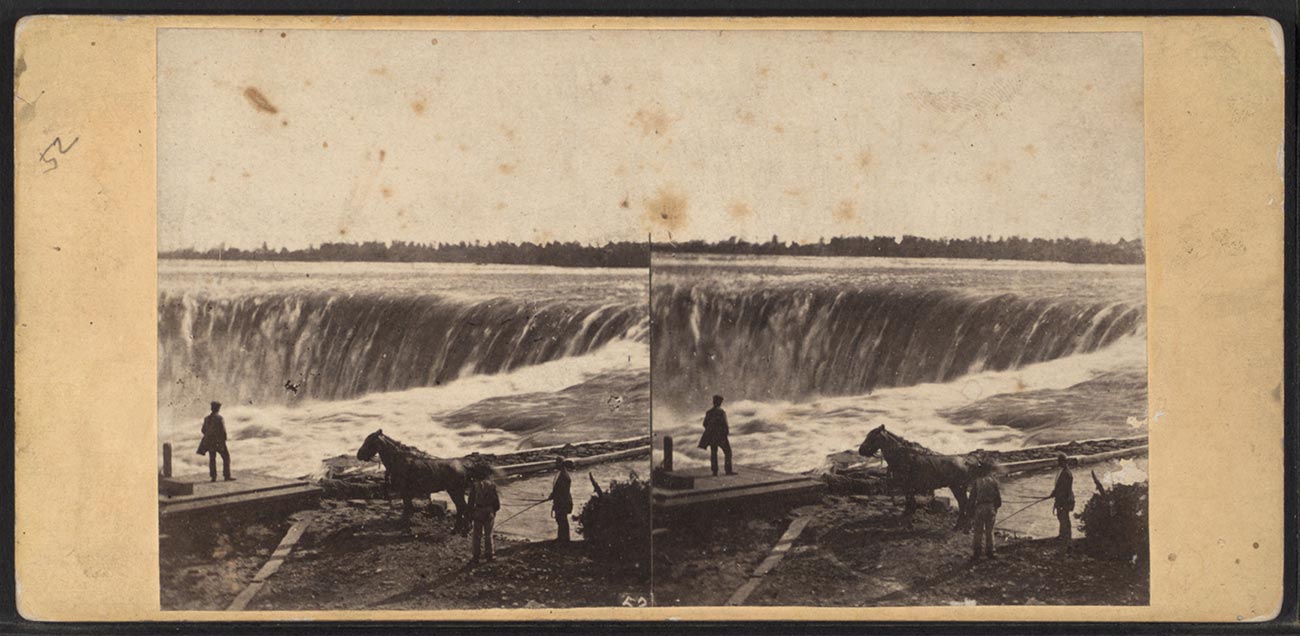

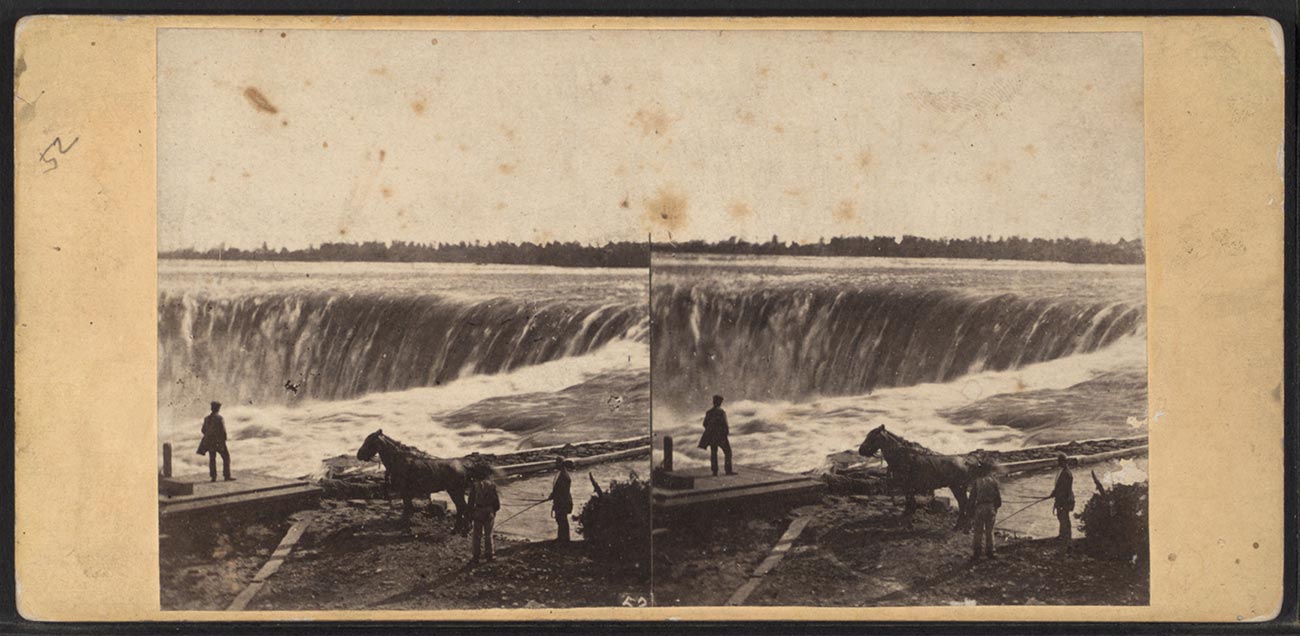

Fig. 4 Edward & Henry T. Anthony & Co. Niagara. The Horse Shoe Fall, ca. 1859-75. Albumen silver prints from glass negatives (stereoscopic views), published by E. & H. T. Anthony & Co. Robert N. Dennis Collection of Stereoscopic Views, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

+

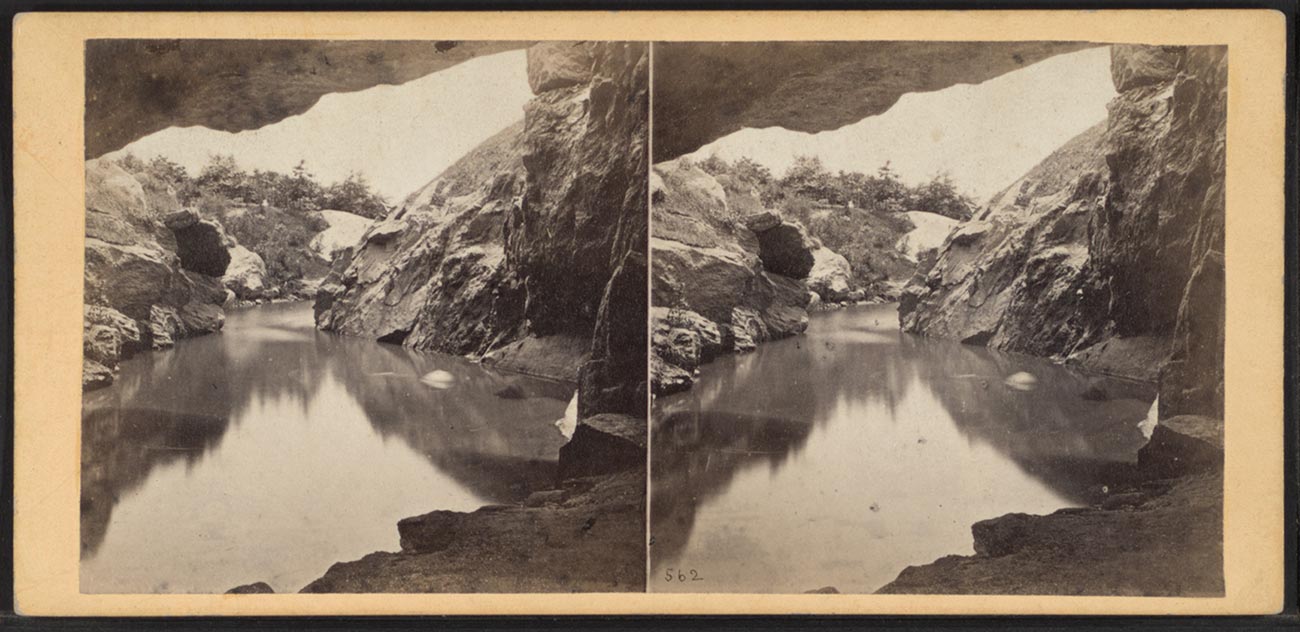

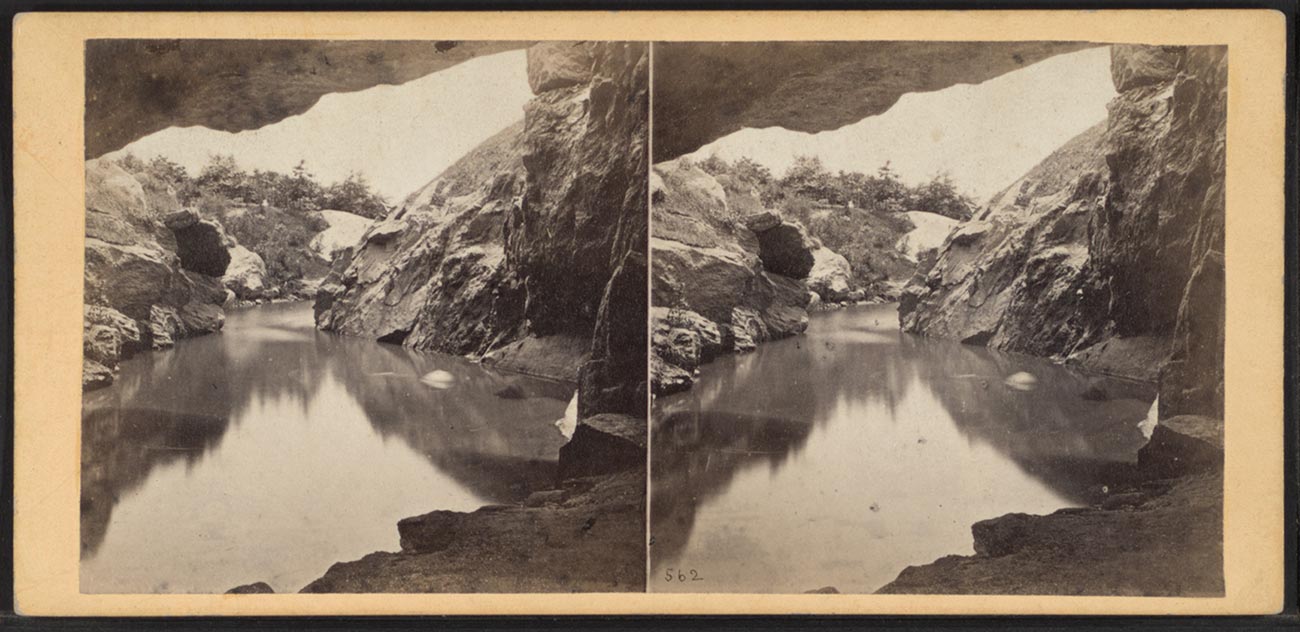

Fig. 5 Edward & Henry T. Anthony & Co. Central Park. View from interior of Cave, looking out, 1860-1875. Albumen silver prints from glass negatives (stereoscopic views), published by E. & H. T. Anthony & Co. Robert N. Dennis Collection of Stereoscopic Views, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

+The extensive catalogue of Anthony & Co. images, taken by either company or commissioned photographers, documented locations across the globe and democratized knowledge by allowing Americans to see distant places for an affordable price, all without leaving their parlors. Images of the United States featured views of new western territories and popular tourist sites such as Niagara Falls (fig. 4). Urban scenes portrayed the main streets and important buildings of New York but also offered many views of the city’s new pastoral leisure space, Central Park (fig. 5). The repetitive appearance of some pictures resulted from the fact that photographers used compositions that reliably enhanced the three-dimensionality of stereoviews, so that the image would seem especially realistic. The similarity of images also established a familiar visual canon that helped consumers to understand busy scenes. A steady growth of the firm’s offerings throughout the second half of the century helped keep it at the forefront of the industry in spite of image piracy, which was common among competitors.

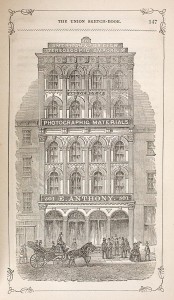

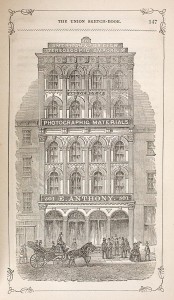

Fig. 6 John C. Gobright (Gobright and Pratt). “Advertisement for E. Anthony, American & Foreign Stereoscopic Emporium.” From The Union Sketch-book: A reliable guide, exhibiting the history and business resources of the leading mercantile and manufacturing firms of New York . . . (New York: Pudney & Russell, 1860). Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

+The Anthonys’ great success and desire for expansion pushed them ever northward up Broadway, paralleling other fashionable retail establishments and residences. The American and Foreign Stereoscopic Emporium at 501 Broadway opened in 1860 (fig. 6). English photographer and writer John Werge recounted his wonderment at the “mammoth” five-story shop: “This establishment is one of the many palaces of commerce on that splendid thoroughfare. The building is of iron, tall and graceful, of the Corinthian order, with Corinthian pilasters, pillars, and capitals. . . . This is the largest store of the kind in New York; I think I may safely say, in either [of] the two continents, east or west, containing a stock of all sorts of photographic goods.” Inside, the sales floor filled with stereoviews and stereoscopes must have looked like the retail display of their competitor Appleton & Co. (fig. 7).

Fig. 7 D. Appleton & Co. Interior view of the D. Appleton & Co. Stereoscopic Emporium, 346 and 348 Broadway, New York. Dealer in every kind of Stereoscopic Views & Instruments, Domestic & Imported, ca. 1860. Hand-colored albumen silver prints from glass negatives (stereoscopic views). The Jeffrey Kraus Collection, www.antiquephotographics.com

+In addition to their contributions to the photographic industry in the form of technology and products, the Anthony brothers sought to positively influence the photographic field and profession through active involvement. They encouraged widespread participation in photography among people on all levels by offering training in their publications and establishing an amateur organization. The self-published monthly periodical Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin, begun in 1870, provided practical information on techniques and technological developments, as well as scholarly articles and, of course, images—both photographs and illustrations. Conveniently, the Bulletin also promoted their goods to a target audience; in addition, the company advertised in other publications, such as Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. Furthermore, Henry founded the Amateur Photographic Exchange Club, which encouraged rising professionals to practice their skills and share their results with others. Such support helped the next generation to succeed in the industry, associated the company name with integrity, and established customer loyalty early in photographers’ careers.

Anthony & Co.’s ethical and strategic business practices made it a well-recognized name in the photographic industry and New York’s manufacturing community. Edward and Henry launched their company’s success through innovation and commercial growth so that their products consistently impressed customers far and wide. Their images documented the urban landscape in a manner never seen before and sold it as a commodity to city residents, visitors, and distant observers alike. In addition, they differentiated themselves from competitors with the quality, affordability, and novelty of their merchandise and by providing unique, entertaining experiences from their retail stores to the parlor. The brothers’ efforts contributed significantly to Broadway’s commercialism and helped to establish New York as an international capital for goods and visual culture.