There is always something new to be seen in Broadway; something is sure to turn up that has never occurred before. A horse will fall down and break his neck by way of variety if nothing else. Stand here when you will, and you are sure to witness a new and novel sight.

— William Bobo, Glimpses of New York

New York City’s nineteenth-century visual culture centered on the spectacle of the streets, and no street loomed larger in the imaginations of both locals and visitors than Broadway. Whether one visited in the daytime for commerce or window-shopping or came in the evening for promenading or the theater, Broadway provided an endless spectacle of diverse peoples, bold advertisements, famous landmarks, and events. The spectacle did not stop at the city limits; printmakers and authors seized upon the comical and the praiseworthy, with a good dose of danger, in their images and guidebooks, which circulated throughout America and across the globe. The sensationalist press made sure to capture the lower-cost east side of the street along with depictions of the city’s marginal residents, the beggars and prostitutes.

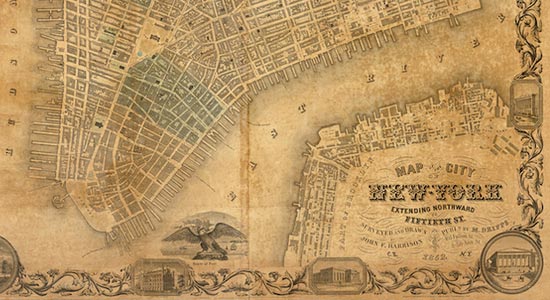

Fig. 1 August Köllner. Broad-Way, New York, 1850. Lithograph, lithographer after Isidore-Laurent Deroy, printed by Cattier, Paris, published by Goupil & Co., New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Susan Dwight Bliss, 1966 (67.630.36).

+The scenic Broad-way, New York by August Köllner (fig. 1) captures the busy nature of the city’s most popular thoroughfare, which connected uptown and downtown Manhattan. Köllner was a Philadelphia-based artist, etcher, engraver, and lithographer who immigrated to the United States in 1839. Broad-way was part of his ambitious project to make more than one hundred drawings of American and Canadian cities, which resulted in fifty-four lithographs published in New York and Paris between 1848 and 1851. These prints offer a view of New York streets at a time when photographic realism was already valued, just before photography became widely available. Like Broad-way, Köllner’s cityscapes often included people, traffic, and horses, which were favorite subjects in his early career.

Broad-way features a lively everyday scene at the south end of City Hall Park, with pedestrians, equestrians, carriages, and omnibuses moving along the streets and sidewalks. Multistory buildings display the grand scale of Broadway’s mid-century architecture, some of which are decorated with flags, signs, and advertisements. The area’s religious and commercial landmarks are visible, such as Trinity Church in the foreground. The Astor House (previously known as the Park Hotel) is the five-story building to the immediate right. A sign for Mathew Brady’s daguerreotype studio at the corner of Broadway and Fulton Street can also be seen, situated north of St. Paul’s Church (both on right). Barnum’s American Museum (distant left) was situated on Broadway between Ann and Fulton Streets, where it stood from 1830 to 1865. The museum was a very popular destination for diverse audiences and also contributed to the area’s traffic (see Kelly-Bowditch, Barnum’s American Museum). The Köllner lithograph indicates the commotion in the area, although the scene is relatively orderly. In contrast, William Bobo describes a more overwhelming Broadway and its traffic in his 1852 guidebook Glimpses of New York City: “See what an amount of moving matter. The white tops of the omnibuses resemble the waves of the ocean—and it looks like we might walk from one end of Broadway to the other upon them, without the slightest difficulty. You would imagine that hardly another could be got into the street, yet it is like dropping one more drop of water into a river. The throng upon the sidewalks—see what a continual press, and one would suppose that it might cease after a while; not so—the only difference is that, now and then, it increases very perceivably, but never lessens.”

To any onlooker, the “moving matter” along this street was extraordinary, perhaps unbelievable. The city relied upon roughly 40,000 working horses, leading to the production of about 400 tons of daily waste, including manure. New York’s urban grid that was planned in 1811 became overwhelmed by the crush of population growth (from 60,000 to 3.5 million people over the nineteenth century) and the density of that population. The period’s images and texts, like those in Harper’s Weekly, depicted these urban shortcomings, warning people to remain alert when navigating the city streets, and they also provided sensationalist entertainment in readers’ homes and parlors.

Fig. 2 Thomas Benecke. Sleighing in New York, 1855. Chromolithograph with hand-coloring, printed by Nagel and Lewis, published by Emil Seitz. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Edward W. C. Arnold Collection of New York Prints, Maps and Pictures, Bequest of Edward W. C. Arnold, 1954 (54.90.1061).

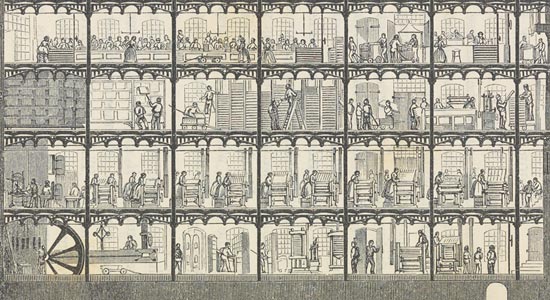

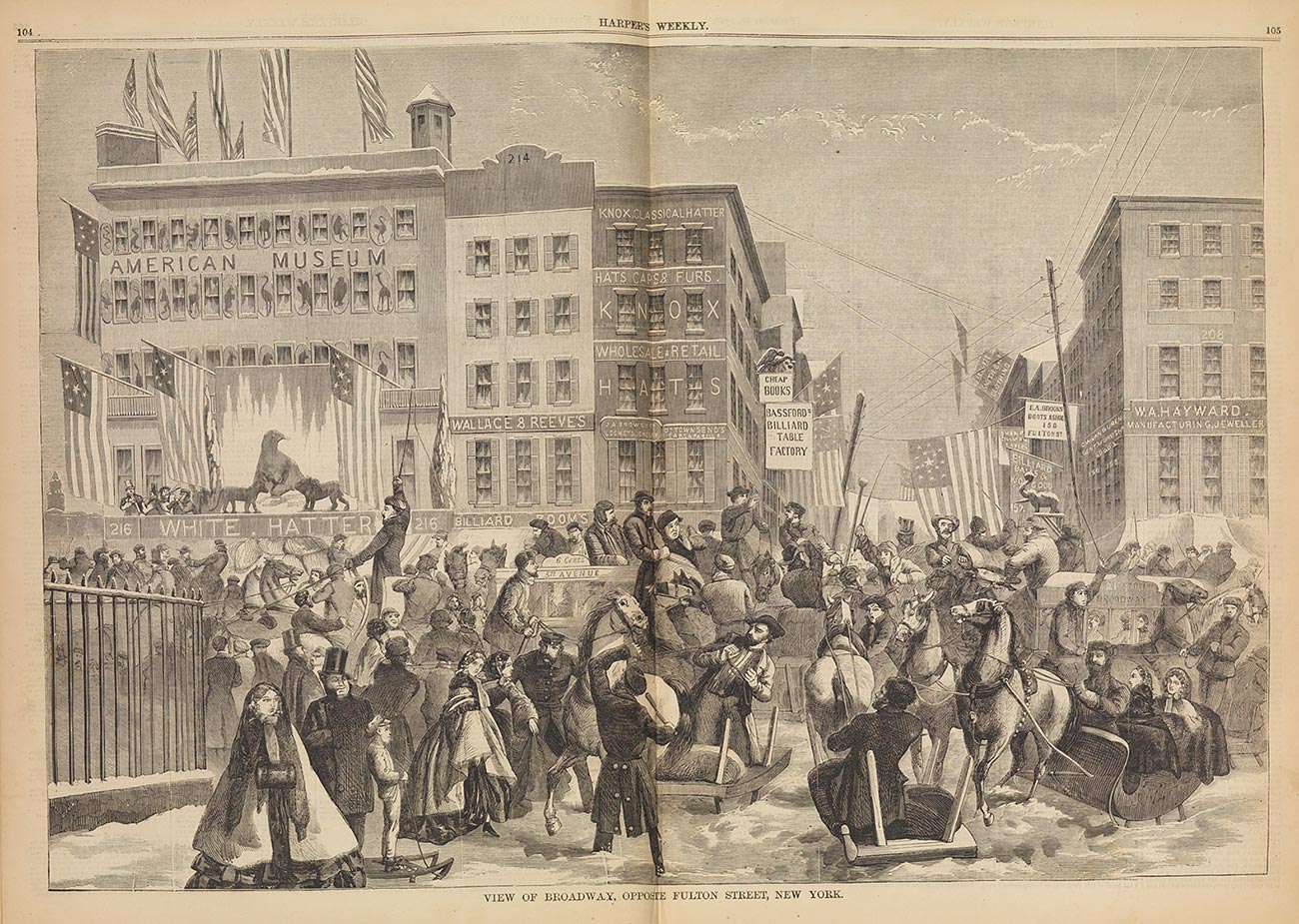

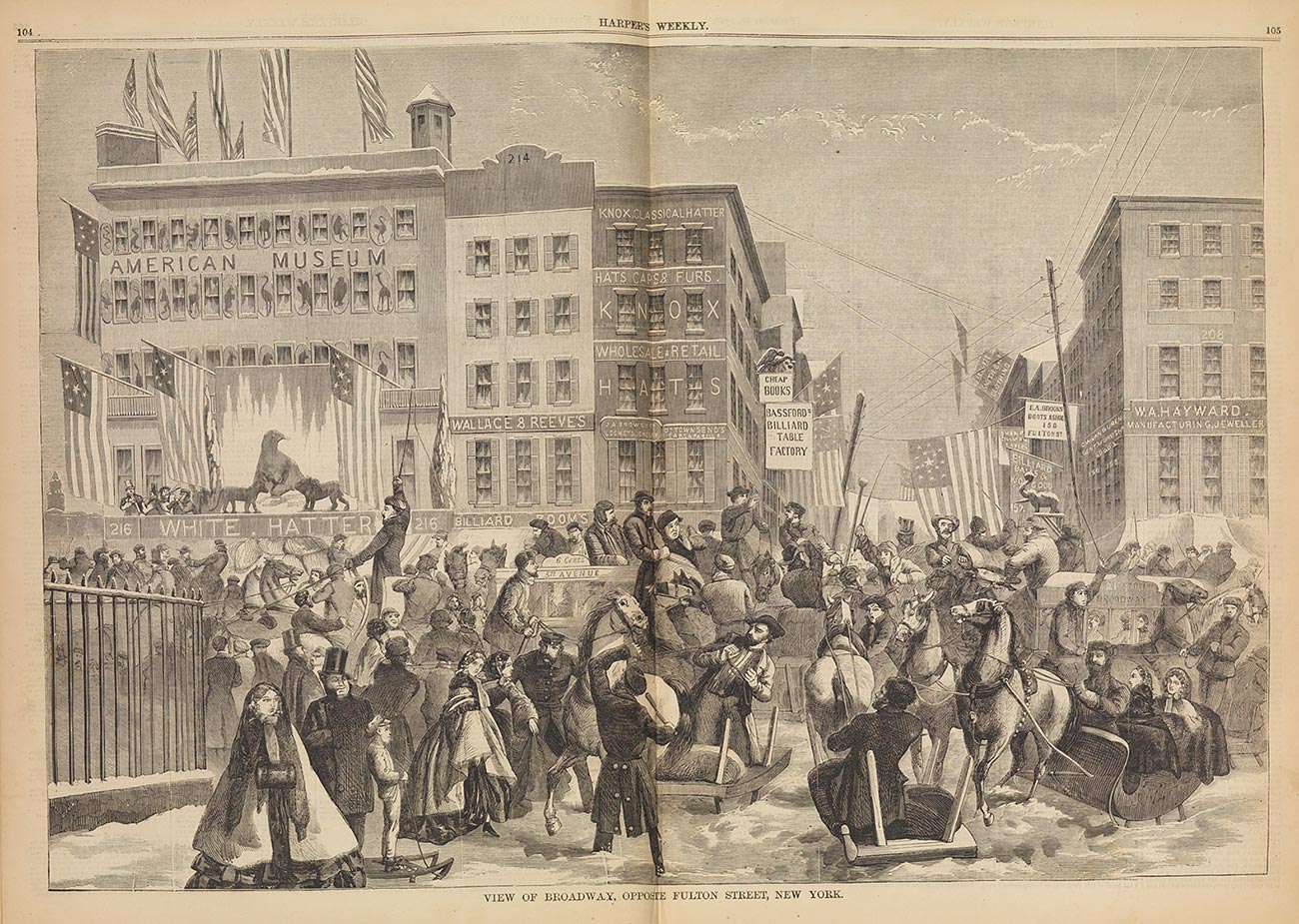

+A whimsical perspective of city traffic and congestion can be seen in the vividly colored lithograph Sleighing in New York, 1855 (fig. 2) by Thomas Benecke. A black and white woodcut with a similar scene also appeared in Harper’s Weekly on February 8, 1860, with the title “View of Broadway, Opposite Fulton Street, New York” (fig. 3). Like Köllner’s work, both of these images show carriages, horses, and pedestrians navigating the corners of Broadway and Fulton Streets and Broadway and Ann Streets, which were dominated by Barnum’s American Museum. However, the artists have moved in closer to emphasize the crowds and the chaos at street level. The chaos must also have been aural, as both images feature Barnum’s musicians performing on the museum’s balcony, offering free but terrible music to drive passersby into the museum in order to escape the cacophony.

Fig. 3 “View of Broadway, Opposite Fulton Street, New York.” From Harper’s Weekly, February 18, 1860. Library, Bard Graduate Center. Photographer: Bruce White.

+Both images pinpoint the difficulties of sleighing after the snow turned to mud, indicating that weather conditions affected daily commercial activity. The Harper’s Weekly woodcut with its larger-scale scene includes policemen with whips and batons in the foreground trying to establish order and authority amid the chaos. Gentlewomen and children were often escorted across the busy intersections, where colliding carriages and other traffic accidents were not uncommon. As Bobo described Broadway, “It has become quite difficult to cross this street, and whenever attempted it is at the peril of your life or limbs.” In addition to these concerns was the risk of soiling one’s white undergarments while sloshing through the muck.

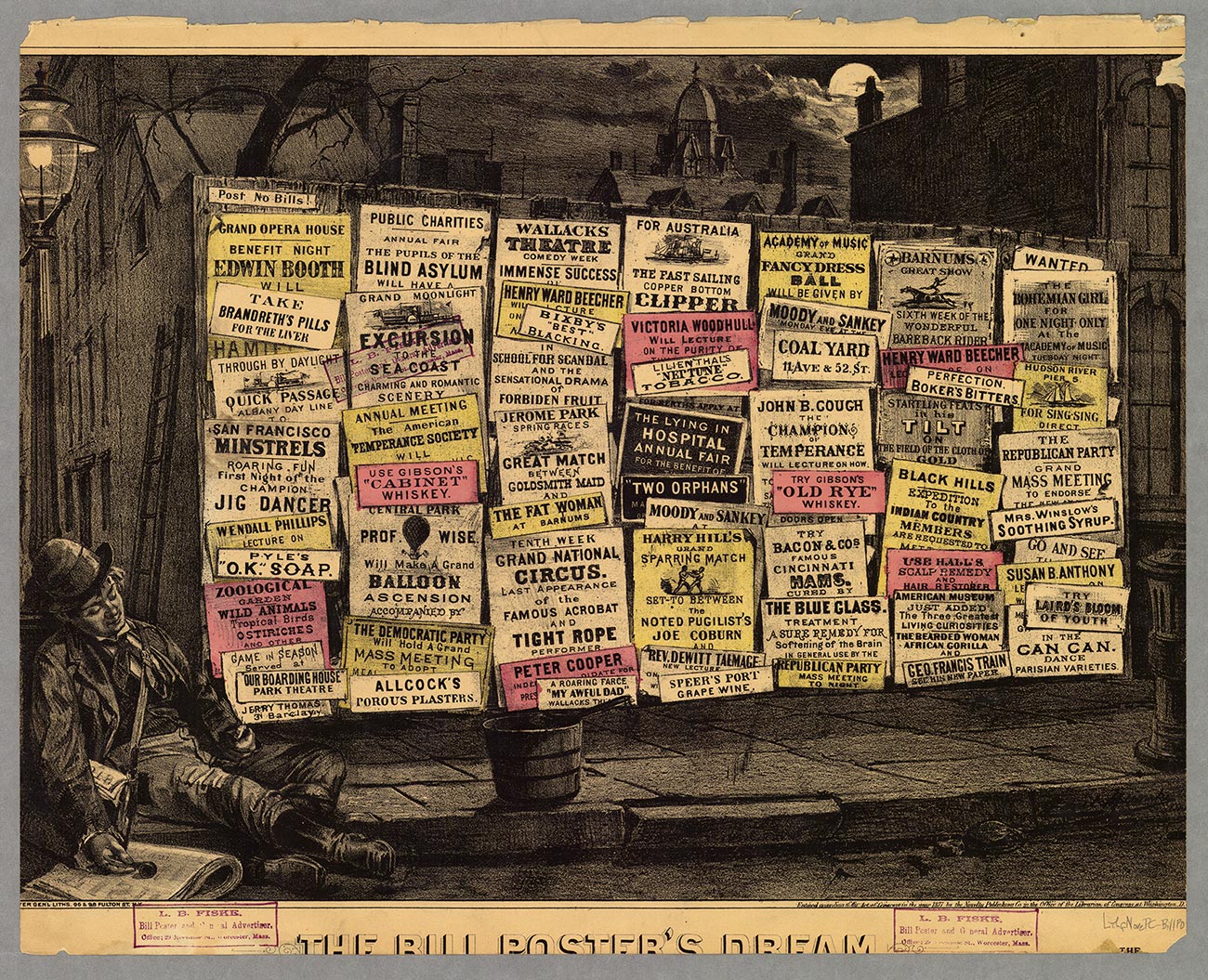

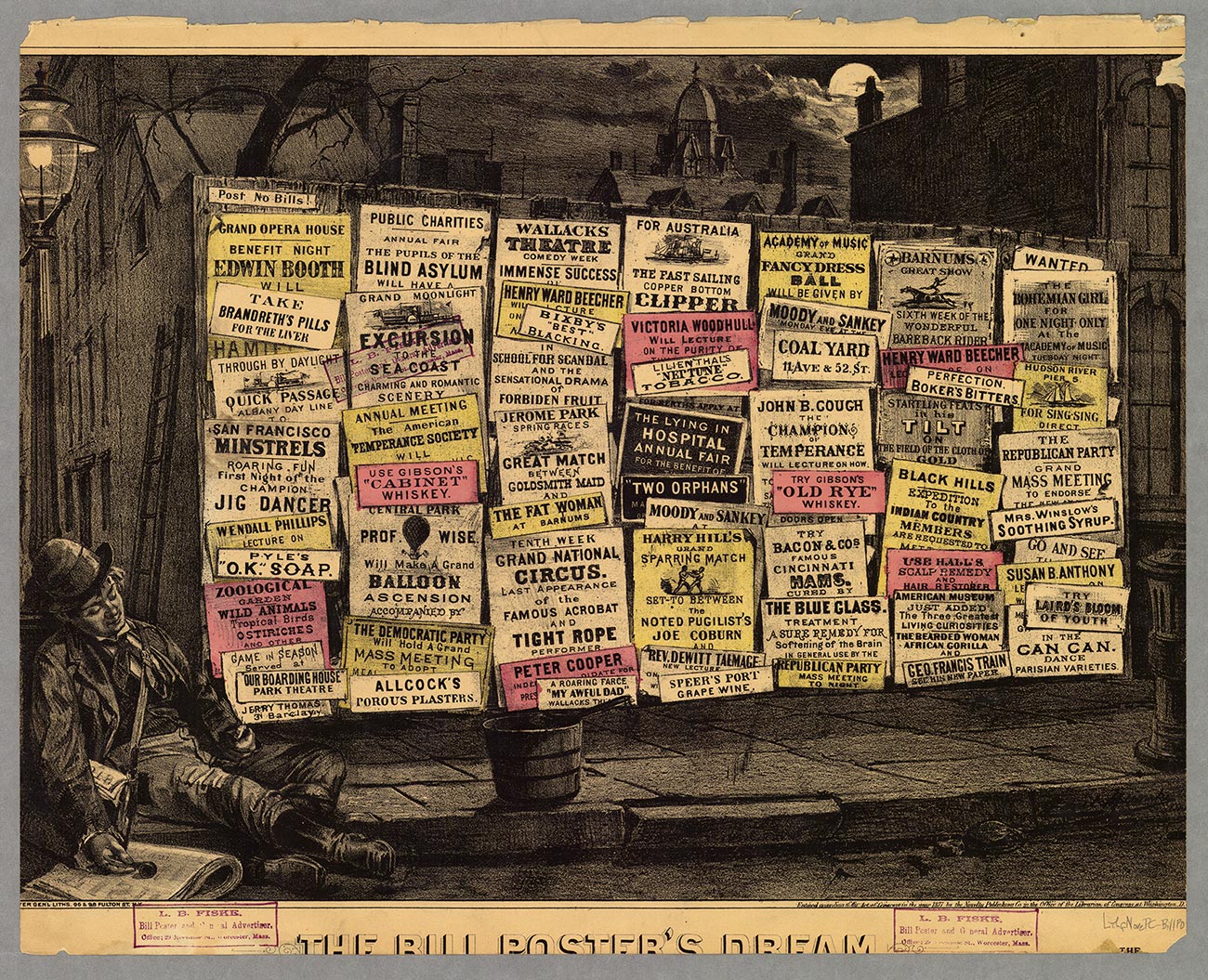

In addition to the teeming spectacle of people and traffic traversing the intersections, advertisements emblazoned on Broadway’s buildings, structures, and even bodies amplified the visual commotion of the streets. The city’s commercial boom promoted greater publicity, and the era’s new printing technologies allowed for these visual representations to be plastered on billboards, street signage, building walls, newspaper stands, and even public property, such as street lamps. Nothing was sacrosanct; people circulated wearing sandwich boards and distributing handbills and trade cards, adding to the pedestrian congestion and sensory overload on the sidewalks. These small advertisements and business cards promoted an array of the city’s commercial industries such as daguerreotype studios and hotels, many of them located on Broadway. The passing of these ephemeral materials from one person to another facilitated encounters between strangers, sometimes even between members of different social classes. By the 1850s and 1860s, signs that read “Post No Bills” were placed on walls and lampposts around the city, but these proved to be largely unsuccessful at restricting the proliferation of advertisements.

Fig. 4 The Bill Poster’s Dream, 1862. Lithograph with color, published by B. Derby, New York. Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

+The Bill Poster’s Dream (fig. 4) from 1862 comments comically on this advertising mania. Below the title, the artist gives instructions for unpacking this piece: “Cross Readings, To Be Read Downward.” For example, the combination of two posters (at top, left) reads “People’s Candidate for Mayor / The Hippopotamus…” while another sequence reads (at center, bottom) “Fashion Course, Great Match between Ethan Allen and / The Fat Woman. . . .” At the bottom left of the lithograph, a satisfied, sleeping billposter decompresses from his hard work, with batches of fliers still in hand. The mixing and mingling of the signs on this imaginative billboard echoes the extraordinary convergence of people in the street.

Downtown Broadway’s commercial opportunities brought throngs of people to the area. The city’s industrialization, technological strides, and urban population growth became evident as individuals converged at busy intersections and popular landmarks, causing congestion and gridlock that stemmed from the main thoroughfares. Fulton Street, for example, absorbed the traffic from the docks that flowed east to west and became especially choked up at its meeting point with Broadway. The fact that the commercial and industrial entities on downtown Broadway were heavily promoted by advertisements, signs, and periodicals indicates that literacy rates were very high in the city. Clearly, the masses were expected to digest and share the endless amounts of the information offered on the streets. Foreigners and locals alike observed Broadway’s teeming commerce and processed their observations in visually stimulating artwork and humorous texts that circulated throughout the United States and Europe. The proliferation of the popular press continued this narrative, labeling this area as a spectacle. Whether for the sake of criticism, boosterism, or sheer entertainment, the downtown commercial center of New York in general, and Broadway in particular, became popular subjects for visualization.