Mid-century New York City was a mystery to those who were unfamiliar with its stratified society, contrasting neighborhoods, and diverse populations. City guidebooks and illustrated newspapers offered to decode these urban complexities for readers struggling to understand the rapidly expanding metropolis. To enliven their descriptions of the city, the authors and illustrators added theatrical sensationalism with themes of light and darkness in text and image. These contrasting images, representing the richest and poorest sections of the city, appealed to a middle-class audience fascinated by tales of both the opulence and the depravity in New York. Many of the guidebook names, such as Sunlight and Shadow in New York and Lights and Shadows of New York Life, indicate how central the contrasting images were to these depictions of the city. Likewise, by midcentury, Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper featured woodcuts that juxtaposed light and dark scenes. These scenes allowed the guidebooks and pictorial newspapers to construct a simplified vision of a metropolis riven by two classes, divided by a moral geography, and populated by social types.

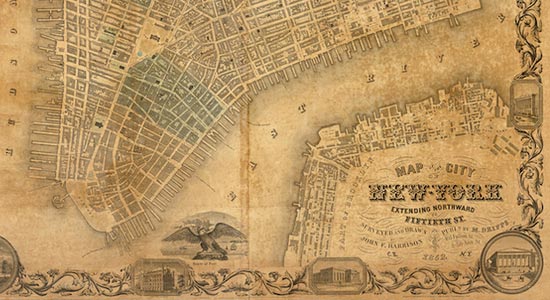

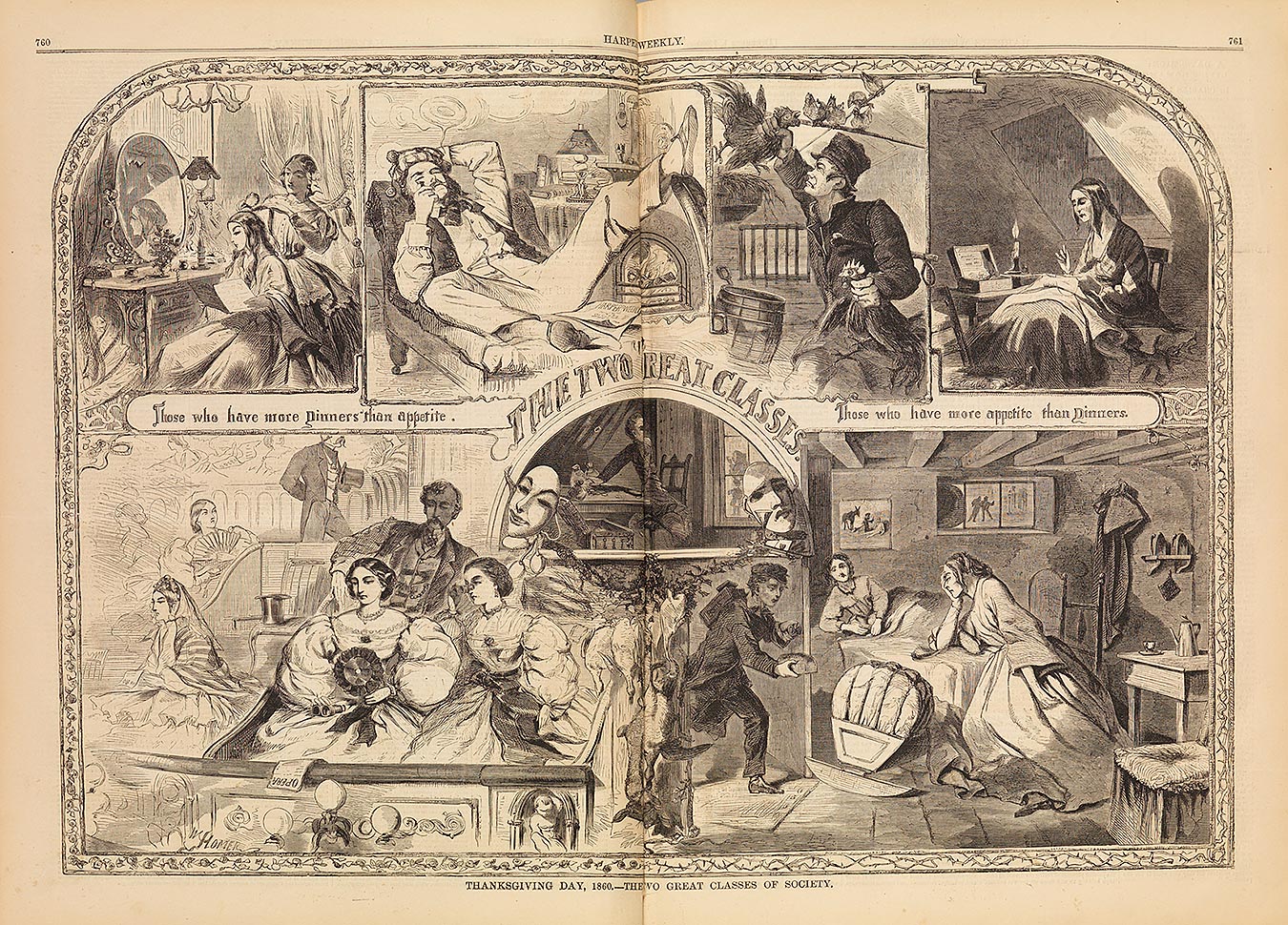

Fig. 1 Winslow Homer. “Thanksgiving Day, 1860 – The Two Great Classes of Society.” From Harper’s Weekly, December 1, 1860. Library, Bard Graduate Center. Photographer: Bruce White.

+Linked sensational depictions of urban life in the pictorial news and guidebooks portrayed a highly schematic version of New York society that was separated into only two distinct classes. Junius Henri Browne claimed in his 1869 guidebook that “[i]n the Metropolis, more than in any other American city, there are two great and distinct classes of people—those who pass their days in trying to make money enough to live; and those who, having more than enough, are troubled about the manner of spending it.” The contrasting scenes of light and darkness in both Winslow Homer’s wood engraving “Thanksgiving Day, 1860 – The Two Great Classes of Society” (fig. 1) and Browne’s guidebook The Great Metropolis capture the reader’s attention and set the stage for a symbolic illustration of class disparity in mid-century New York. Through the use of text, both Homer and Browne describe the two great classes, respectively: the rich have “more meals than appetite” (Homer) and “more than enough money to survive” (Browne), while the poor have “more appetite than meals” (Homer) and struggle to “make enough money to live” (Browne).

In his image Homer emphasizes the contrast between the bright, opulent side of the wealthy and the dark, shadowy side of the poor. The left side of the picture features well-lit interiors that illuminate the protagonists in the scene. These interiors resemble the lavish textual depictions of the wealthy mansions in The Great Metropolis, where “all is warmth, and color, and richness, and perfume. The gilded drawing-rooms are crowded with a confusion of silks, and velvets, and laces, and broadcloth, and flowers, and jewels.” The main characters in Homer’s illustration are all engaged in some leisurely activity, from smoking by the fire to attending an opera. The “background” characters, the working-class maid, and the male pickpocket behind the wealthy woman have shadowy faces that distinguish them from their wealthier or more virtuous counterparts.

At the right side of Homer’s illustration, however, the lack of lighting creates a dismal scene, which emphasizes the haggard shadows on the characters’ faces. These rooms are much like the “wretched tenement houses” that Browne describes in his text, where “a family [lives] in every room here, and sickness, and debauch, and poverty, and pain on every floor.” Whereas the wealthy experience “no shadows, no frowns, no haunting cares,” those on the right experience only those dark realities, echoing Browne’s descriptions.

A complex system of linked word and image unites Homer’s details and Browne’s supporting text and serves to emphasize the immense contrast between the two classes of New York. The periodical’s wood engraving and the guidebook’s text each use theatrical depictions of light and shadows to attract a readership interested in the popular theater and eager to understand the complex social structures of the sensationalist metropolis.

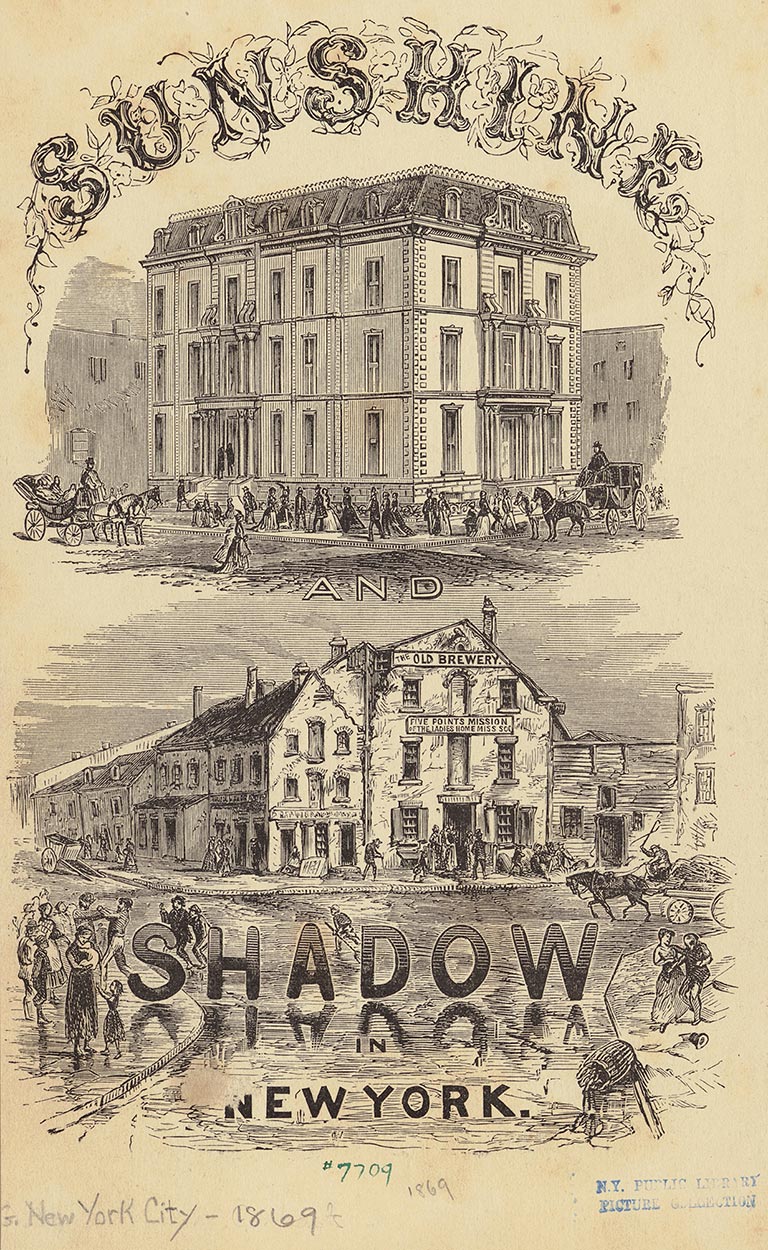

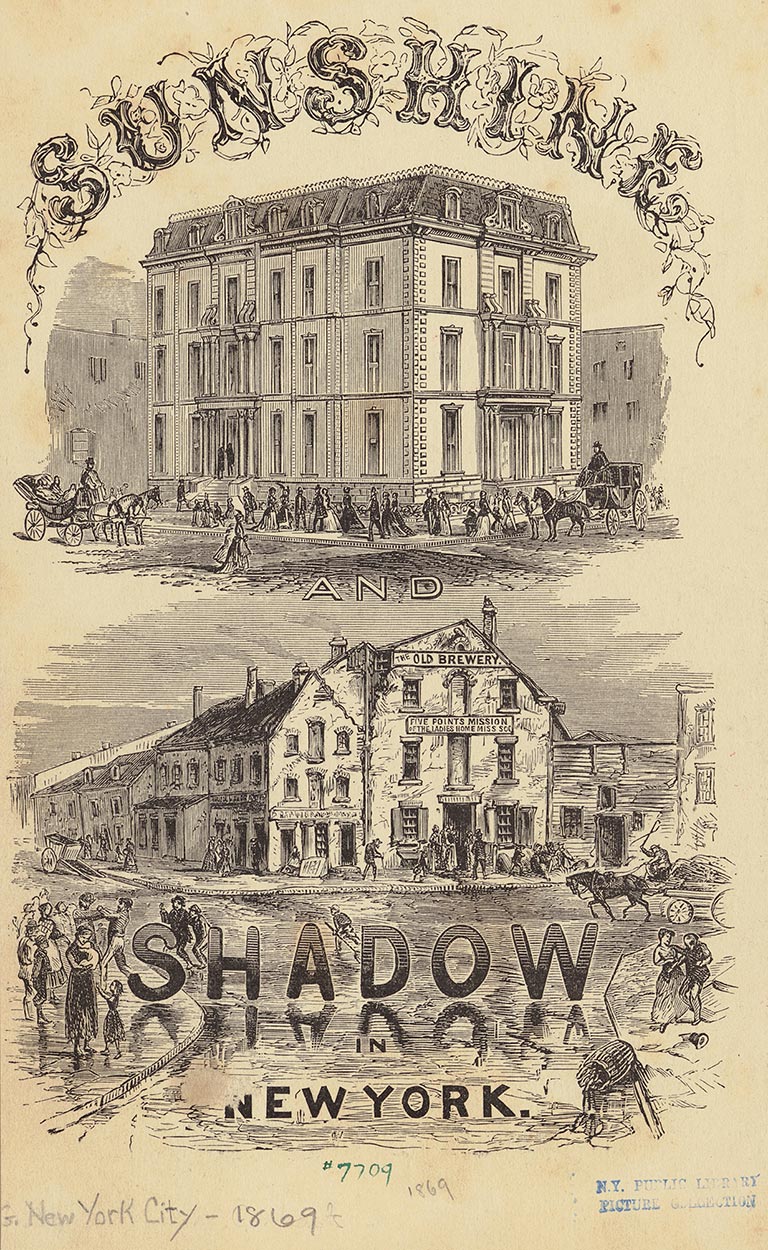

Fig. 2 Frontispiece to Matthew Hale Smith, Sunshine and Shadow in New York (New York: J.B. Burr, 1868). Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

+In a similar way, through eye-catching visuals and dramatic descriptions, periodical and guidebook authors and illustrators mapped the city into symbolic zones of the rich and the poor. In the frontispiece of Matthew Hale Smith’s Sunshine and Shadow in New York (fig. 2), and in the text of James Henry McCabe’s guidebook Lights and Shadows of New York Life, the extremes of sunlight and shadow represent the richest and poorest neighborhoods in New York. The “bright and cheerful scene” in the upper image of Smith’s illustration closely echoes McCabe’s text, in which he describes the city as follows:

You may stand in the open space at . . . the true Five Points, in the midst of a wide sea of sin and suffering, and gaze right into Broadway with its marble palaces of trade, its busy, well-dressed throng, and its roar and bustle so indicative of wealth and prosperity. It is almost within pistol shot, but what a wide gulf lies between the two thoroughfares, a gulf that the wretched, shabby, dirty creatures who go slouching by you may never cross. There everything is bright and cheerful. Here every surrounding is dark and wretched. The streets are narrow and dirty, the dwellings are foul and gloomy. . . . This is the realm of Poverty.

The building in the upper half of Smith’s illustration closely resembles drawings of A. T. Stewart’s marble-faced mansion on Fifth Avenue and Thirty-fourth Street, completed the same year that McCabe’s guidebook was published. This positive depiction of the mansion signifies the height of opulence and the morality of the rich who lived on Fifth Avenue and visited the “marble-palaces of trade” on Broadway.

The corresponding “dark and wretched scene” of the lower image, showing the Old Brewery and the Five Points Ladies’ Mission, represented all that the Five Points symbolized in the New York imagination: the misery and vice of the poor and criminals. McCabe’s chapter about the neighborhood, “Life in the Shadow,” depicts the area in richly descriptive text that closely mirrors Smith’s image. The Old Brewery with its dilapidated exterior appears “foul and gloomy,” and the surrounding streets appear dirty with trash and other debris. The artist depicts the “creatures” in the lower image in a “wretched, shabby, dirty” manner: the carriage driver is shown whipping his horse violently, and a man and woman on the street appear to be having a physical dispute. The children clad in their rags run about the streets and are fighting as well. Illustration and text in New York City guidebooks worked together to present to the public an image of the Five Points neighborhood that was mired in poverty and vice.

Pictorial newspapers and guidebooks alike divided the city’s neighborhoods into “sunshine” or “shadow” areas with respective moral qualities, and both image and text captured the imagination of readers and instructed them about the sensationalist metropolis. Armed with this “moral geography,” as guidebook author George Foster called it, the readers would then know how to navigate the highly stratified regions of the city while keeping to their respectable sections.

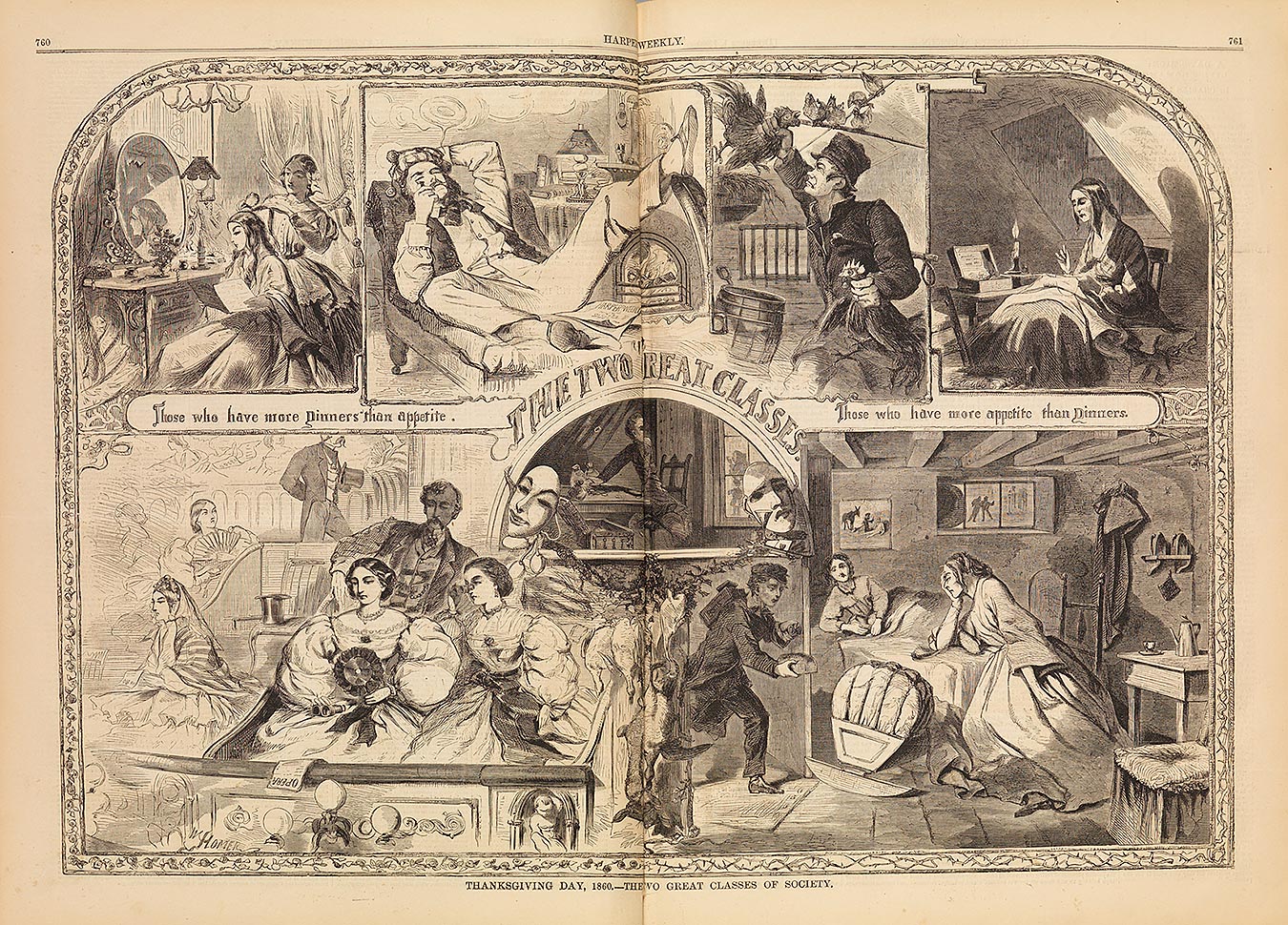

The population of New York was becoming an agglomeration of increasingly diversified groups, which the print culture offered to decode and classify for its unknowing readers. The guidebooks and newspapers presented many “social types,” which often appeared as sensational, theatrical caricatures, particularly in the case of the working class. James McCabe described these types with a great literary flourish: “O, for the pencil of a Beard or a Bellew, to portray those saucy pug-noses, those dirty and begrimed faces! Faces with bars of blacking, like the shadows of small gridirons—faces with woeful bruised peepers—faces with fun-flashing eyes—faces of striplings, yet so old and haggard—faces full of evil and deceit.”

Fig. 3 “A ‘Dead Rabbit’ Sketched from Life” and “A ‘Bowery Boy’ Sketched from Life.” From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, July 18, 1857. Courtesy American Social History Project, Graduate Center, City University of New York.

+The dark and dangerous-looking Five Points man embodied in the “Dead Rabbit” illustration represented one of these characters (fig. 3). Sometimes recognizable as the “Five Points Tough,” here he belongs to a specific gang and ethnic group, the Dead Rabbits, a gang of Irish immigrants who battled the nativist Bowery Boys over a political dispute in 1857. Caricatures like these helped propagate the idea that the poor were dangerous and undeserving of sympathy. Thus, even though they were “anonymous,” they symbolized the poor morality of certain groups and contributed to negative stereotypes of immigrants and others. The guidebooks also illustrated these unsavory individuals. In the quote above, McCabe depicts the character of “Horace” in the Bowery Theatre, a representative of the “Five Points Tough.” The similarity is evident between the Dead Rabbit illustration and the description of the shadowy, criminal “saucy pug-noses, those dirty and begrimed faces” seen in the theater. It is not surprising that such a negative depiction of the Dead Rabbit neighborhood would appear in a theater located in the heart of the Bowery Boys’ territory, but this character mirrored one that was already widespread throughout print and theater culture.

The social types in guidebooks and pictorial newspapers served as a theatrical kind of entertainment but also offered the unknowing reader a way to categorize the ever-increasing population of the metropolis. These stereotyped images were reaffirmed in texts and even recycled in theater performances. Using well-established conventions of light and shadow, these social types identified certain groups of people and taught readers how to view them so that they could find their place in the social spectrum of the metropolis.

Theatrical themes of light and shadows in depictions of classes, neighborhoods, and social types attracted the mid-century reader because of their sensational appeal, particularly in their depictions of working-class communities. Far from being simple commercial gimmicks to increase circulation, the themes helped the reader to decode and visualize a city in terms of rich/poor, vice/virtue, and other basic paradigms. In doing so, they offered valuable instruction to those who were trying to comprehend the enormity and social complexity of the emerging metropolis. As George Foster noted, these “urban sketches” served to “interest while they instruct.”

Although both guidebook texts and newspaper images used similar strategies to depict the metropolis, the implications of these depictions differed greatly. Whereas the guidebook authors used conventions common in sensational novels and embellished them with real-life details, the newspaper illustrators embellished real-life events with novel-like sensationalism. Thus, while the guidebook readers would have understood the sensationalism as fictional, the readers of illustrated newspapers were likely more credulous. If they believed, as Frank Leslie claimed, that his newspapers were “giving to the public original, accurate, and faithful representations of the most prominent events of the day,” the readers risked blurring the lines between fact and sensational fiction in their understanding of the metropolis.