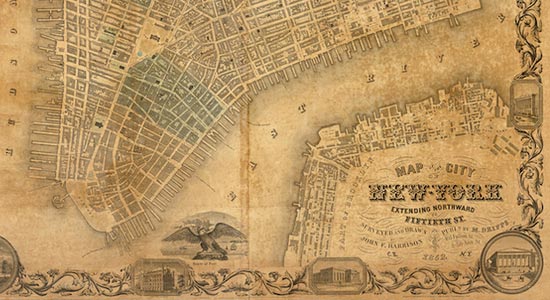

Fig. 1 Henry A. Papprill, after John William Hill. New York from the Steeple of St. Paul’s Church, Looking East, South, and West, 1848. Color aquatint and etching; second state of three, published by Henry Megarey, New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Edward W. C. Arnold Collection of New York Prints, Maps and Pictures, Bequest of Edward W. C. Arnold, 1954 (54.90.587).

Before New York’s iconic skyscrapers took over the twentieth-century skyline, church steeples, scattered at fairly frequent intervals throughout the nineteenth-century city, loomed as the tallest structures in the urban landscape. As New Yorkers looked heavenward at their city’s church steeples, artists and mapmakers looked down from those heights to survey the growing city at their feet (fig. 1). The intersection at the base of St. Paul’s Chapel, pictured in the print made by Henry A. Papprill after an aquatint by John William (J. W.) Hill, hereafter called the Papprill-Hill View, was the convergence of Broadway, Ann Street, and Fulton Street, a bustling section of Broadway that was home to Barnum’s American Museum, Mathew Brady’s daguerreotype gallery, various shops, the luxurious Astor House hotel, and, of course, the chapel itself. During the middle of the nineteenth century, this hub was transformed from a fashionable residential neighborhood into a chaotic commercial and entertainment district. Barnum’s American Museum, one of the most frequently pictured landmarks, had been a museum for decades when Barnum bought it in 1841, but it was his showmanship and “humbuggery” that made the museum a must-see destination for locals and tourists alike (see Kelly-Bowditch, “Barnum’s American Museum“). Brady’s daguerreotype gallery was one of the most popular in the city at midcentury and drew people interested in seeing his gallery of celebrity portraits as well as to have their own made. Artist J. W. Hill, engraver Henry Papprill, and publisher H. I. Megary certainly used the popularity and legibility of this intersection to their advantage when they chose the St. Paul’s steeple from which to create their elevated view of the city. Many other locations would have been possible, as the other steeples visible in the image attest, but the choice of St. Paul’s, a well-known vantage point for visitors to take in the view from the steeple along with its neighborhood of prominent businesses, speaks to their understanding of the market for prints.

Fig. 2 Henry A. Papprill, after F. Catherwood. New-York. Taken from the North west angle of Fort Columbus, Governor’s Island, 1846. Lithograph, published by Henry Megarey, New York. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

+Views of the city, among the most popular nineteenth-century prints from New York and national printmakers alike, were a diverse group, incorporating street views, steeple views, and bird’s-eye views. These three main categories were valued for their different emphases. Street views reflected the way in which a pedestrian would experience the street, but as the city grew in space and complexity, new visual genres, often from ever loftier perspectives, offered new ways to understand New York City. Steeple views were a logical next step from images made from hilltops and offered a new perspective, but one that was familiar and easily understood. Governor’s Island, off the southern tip of Manhattan, offered Papprill and his collaborators an unobstructed view of the busy downtown area and harbor, enhanced by the vantage offered by Fort Columbus (see fig. 2). Bird’s-eye views, on the other hand, were imagined cityscapes that combined map-like views of the city that made the grid visible with details common in street and steeple views, which made the grid and the ever-expanding city more readable.

Fig. 3 William J. Bennett, after John William Hill. New York, from Brooklyn Heights, 1837. Hand-colored aquatint. Eno Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

+The Papprill view of New York from Governor’s Island and another print, a view from Brooklyn Heights (fig. 3), were collaborative efforts by a group of artists who worked in the small world of printmaking in the city. J. W. Hill, who drew both the view from St. Paul’s steeple and the view from Brooklyn Heights, was the son of a prolific aquatint artist, John Hill, who had worked with William J. Bennett, engraver of the view from Brooklyn Heights. Many artists, including Henry Papprill himself, worked for the publisher Henry I. Megarey, who used traditional means, mainly subscriptions, to sell his higher-end aquatint works. J. W. Hill, who had been a geological surveyor, was involved in many surviving works of the midcentury. Compared to other artists’ sketchy drawings, his precise style is clearly evident in both the Papprill-Hill View and the view from Brooklyn Heights. The printmaking workforce was largely made up of English artists during the first half of the nineteenth century and was clearly influenced by the British taste for aquatints of landscapes and city views.

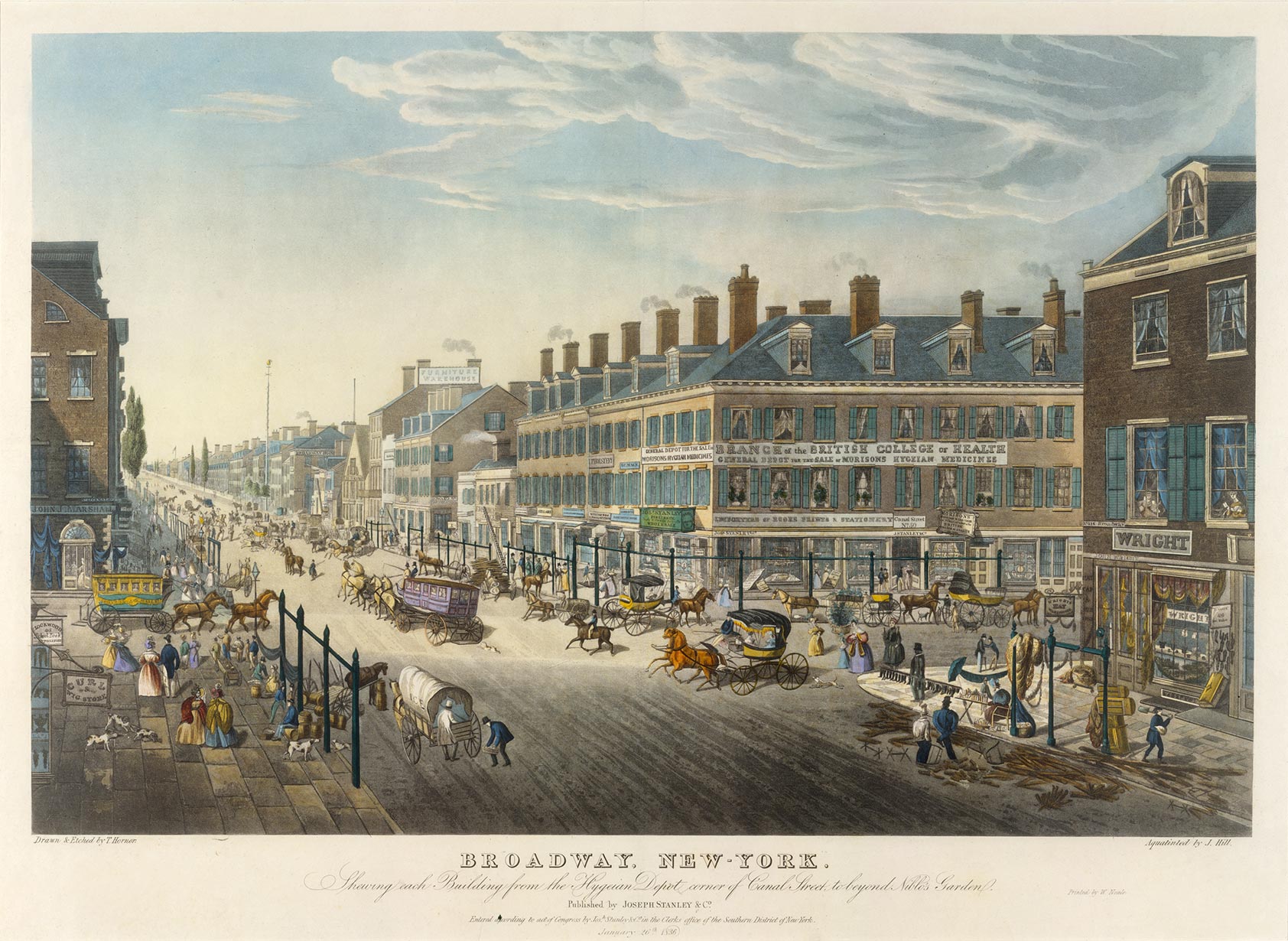

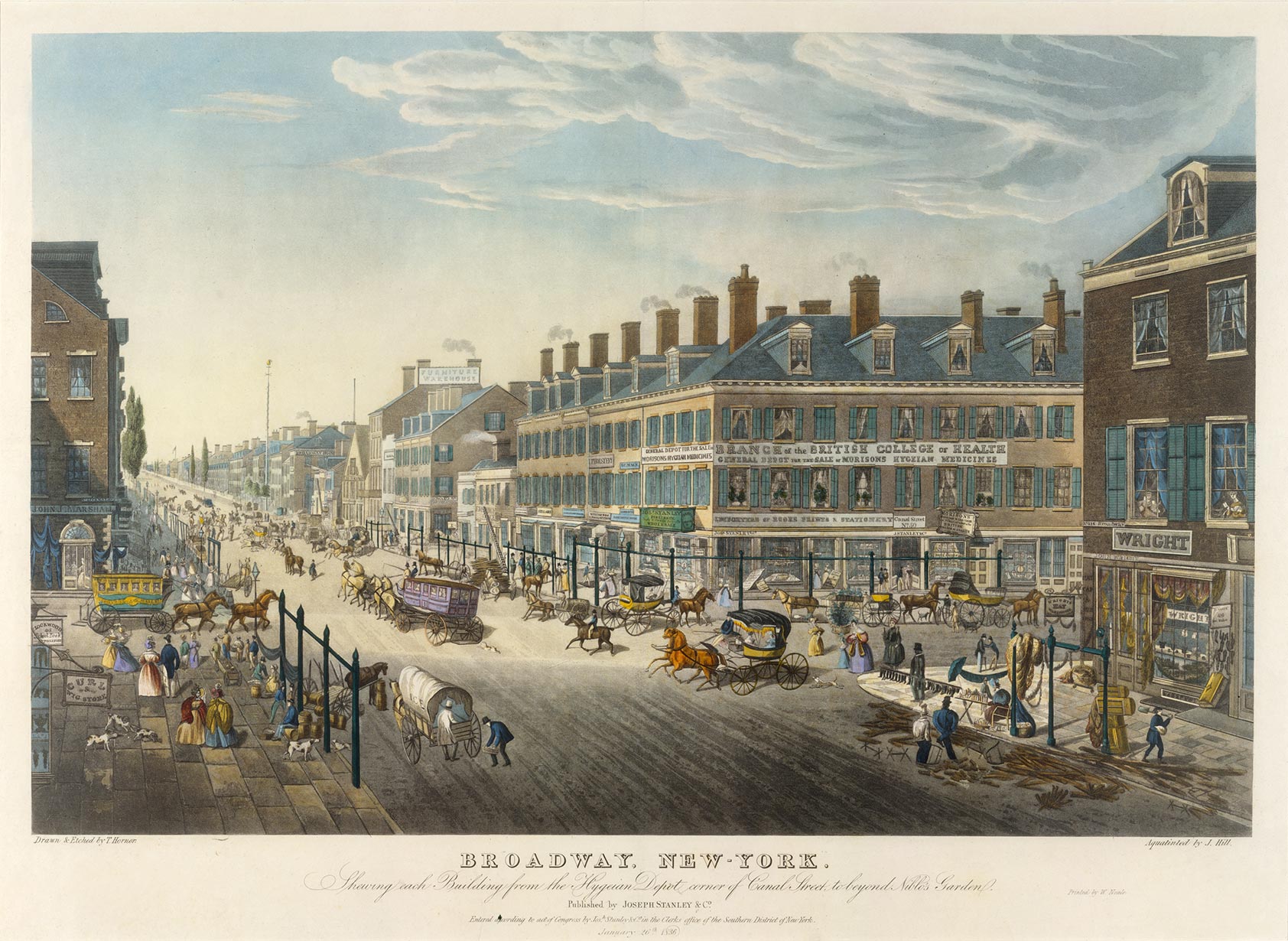

Street views, which were among the first prints offered to the public, showed what a resident or visitor would see standing on a corner or from the first-floor window of a building. These prints often emphasized the tranquility of the wealthier neighborhoods, the bustling commerce of the harbor, or the rowdiness of the poorer districts. Making sense of one’s own neighborhood or trying to understand one that is unfamiliar was certainly one of the purposes of these prints, which functioned in much the same way as maps and guidebooks, of use to both residents and visitors. These images allowed the viewer to peruse the city at leisure without getting caught in crowds, especially in parts of the city populated by groups to which they did not belong. Starting in the 1830s, signs depicted in prints were made legible, allowing the images to function as advertisements and directories. Thomas Hornor’s image of Broadway and Canal Street (fig. 4) displays this lively metropolis to its best advantage, with legible signs advertising the city’s mercantile culture, fashionable and working-class pedestrians, and all the modes of transportation New York City had to offer by 1836 (see Gardner, “The Spectacle of Commercial Chaos and Order“).

Fig. 4 Thomas Hornor. Broadway, New-York. Shewing Each Building from the Hygeian Depot Corner of Canal Street to beyond Niblo’s Garden, 1836. Aquatint and etching with hand-coloring, aquatint by John William Hill, printed by W. Neale, New York, published by Joseph Stanley & Co., New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Edward W. C. Arnold Collection of New York Prints, Maps and Pictures, Bequest of Edward W. C. Arnold, 1954 (54.90.703).

+Artists seeking ways to depict the growing urban sprawl worked from hilltops in Brooklyn or across the river in New Jersey, or from islands in the harbor and other points that gave them a visual advantage. By the 1820s and 1830s, urban views replaced the tranquil hilltop and harbor-centered views of the distant city with pastoral scenes in the foreground. J. W. Hill made reference to this history by depicting birds, dogs, and residential gardens instead of the wilds of New Jersey that had been featured earlier in the century (see fig. 3). In the view from Brooklyn Heights, the distinctly urban foreground reminds the viewer of the growth of New York City, which was spreading ever outward, even into Brooklyn. The scene from this rooftop allows individual buildings to be identified, including many churches, which can be recognized by their steeples. Views from windows, with the architectural details as a built-in frame, were also common, as were images in which the roof of a building was visible below the vantage point, as in the Papprill-Hill View showing New York from St. Paul’s steeple.

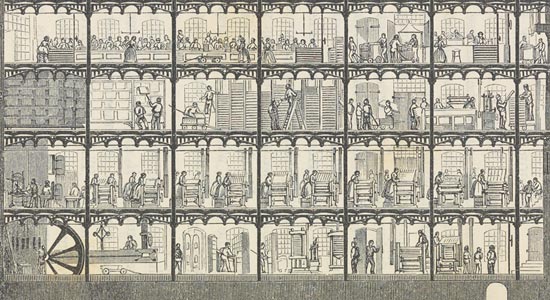

Fig. 5 “View from Trinity-Church Steeple.” From William Cullen Bryant, Picturesque America, or, The land we live in (New York: Appleton, 1872-1874). Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

+Church steeples gave viewers a known vantage point and enabled them to understand what they were seeing, especially when the church structures were included in the image. Trinity Church’s 290-foot steeple held the record for the highest structure in the city until 1890, except for a short period in the 1850s when it was outranked by the Latting Observatory tower attached to the Crystal Palace on Forty-second Street. An image of a young woman at the top of Trinity Church’s steeple in the 1870s (fig. 5) offers a reversed view of images from early in the century, placing the city in the foreground and the pastoral hills in the distance. Those who were willing to climb the many stairs to the top of a steeple could experience the same vista that Hill drew from St. Paul’s Chapel, but his work provided an armchair traveler’s version of the adventure. The Latting Observatory tower offered a purpose-built version of the steeple, giving visitors a 300-foot view of the city from 1853 to 1856, when it burned down. By the time the Latting Observatory was welcoming guests, however, aerial views from balloons (and imagined airborne views) had become popular as well, offering an even greater vantage point from which to see the whole of the city.

Steeples offered a slice of the map, but bird’s-eye views could encompass all of the city and make the city understandable as a whole. Where street views elucidated single blocks and steeple views made neighborhoods legible, views from the sky laid the city out like a map but kept the elements that made the city readable to viewers. Signs, pedestrians, ships, docks, and church steeples were landmarks and signifiers to the viewer, indicating that the city was a real and tangible place, not a series of flat lines on a traditional map. City views offered New Yorkers visible evidence that their city was growing and prospering, in images that emphasized signs and commerce, transportation options, orderly streets and buildings, and the northerly movement of the city’s growth. The Papprill-Hill View offered a new perspective on mid-nineteenth-century New York City and reinforced ideals important to the city’s residents, as well as to viewers all over the country and abroad.