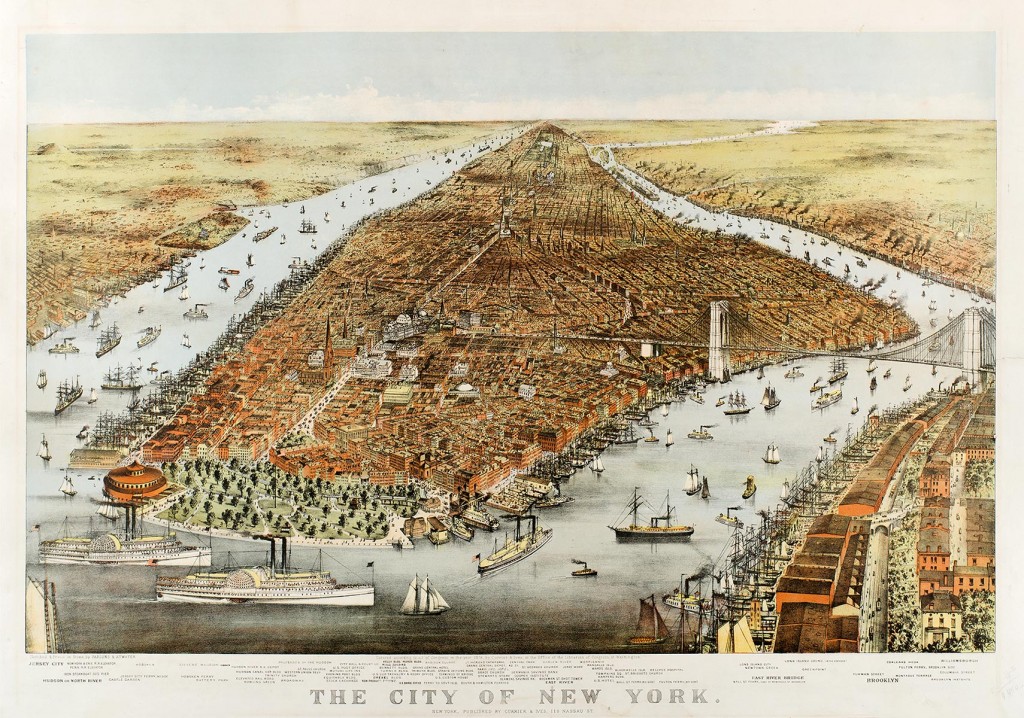

By 1876, when Currier & Ives made available its print entitled The City of New York, with its well-known buildings, prescient Brooklyn Bridge, and a cityscape stretching as far as the eye could see, images of the city, such as the bird’s-eye view, had been circulating for several decades, thanks to new technologies and genres such as lithographs and stereoviews. Nothing stood out more prominently as a visual expression of New York City than Broadway—the leading street of the metropolis—whose constant motion and vibrant life can be clearly seen in this lithograph, and whose exaggerated width dramatically enhances the viewer’s perception of the site (fig. 1).

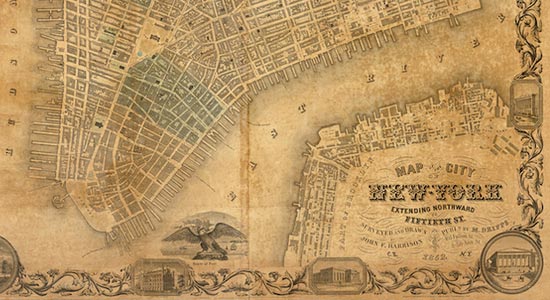

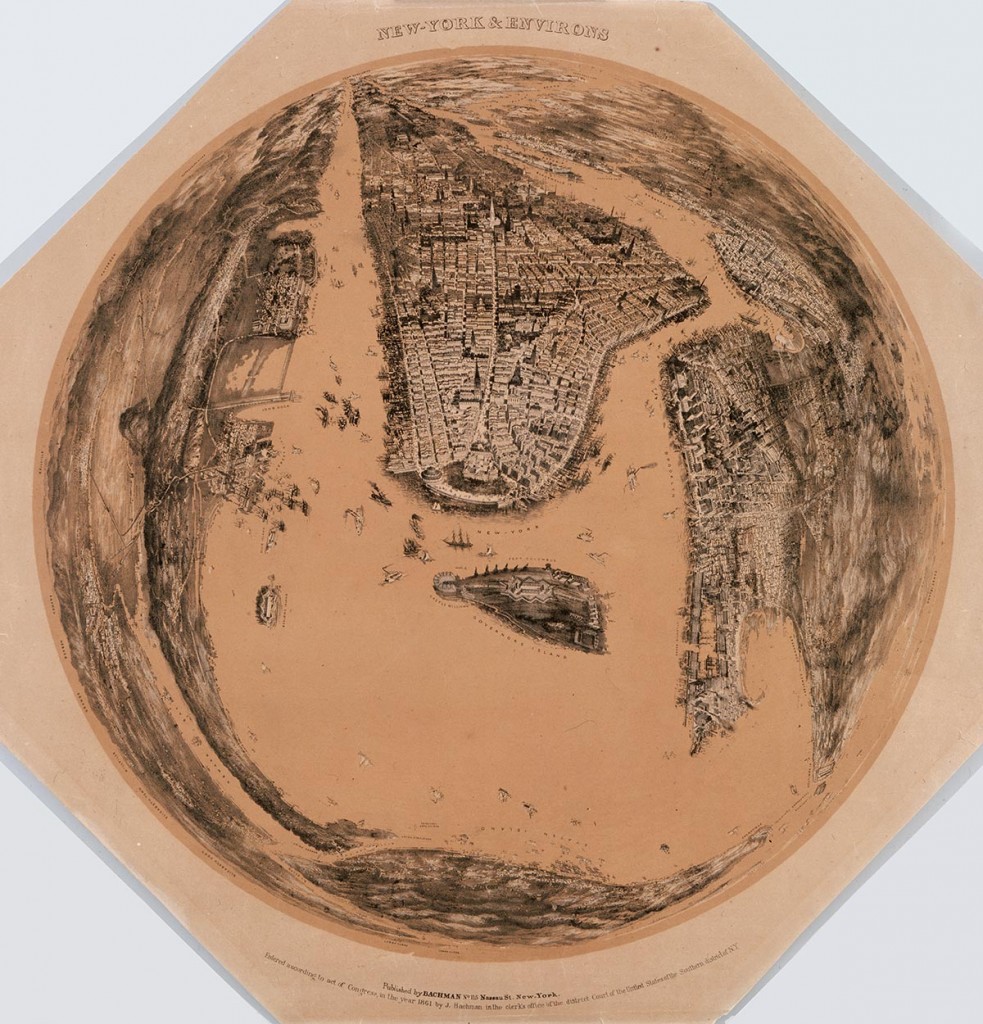

During this same period, every traveler’s account and guidebook featured vivid descriptions of Broadway that emphasized the spectacle of the city’s central thoroughfare. “It is a perfect Kaleidoscope, —each day presenting some new feature of change,” Frederick Saunders wrote in New York in a Nut-Shell in 1853. That same year Cornelius Mathews published a book of sketches and scenes he called A Pen-and-Ink Panorama of New-York City and invited his readers to accompany him on “a panoramic exhibition,” to “paint a home picture,” beginning with Broadway, “a great sheet of glass, through which the whole world is visible as in a transparency.” He thus echoed other writers by viewing this particular street as a microcosm of the city, the nation, and indeed the world. Mathews ended his description with another new visual wonder of the age, “the Bird’s-eye View of New York.”

These images and words make it clear that nineteenth-century New York City was a not-to-be-missed visual experience for resident and visitor alike. These writers, graphic artists, publishers, and printers were convinced that the nineteenth-century city could best be captured and understood through the use of visual representations.

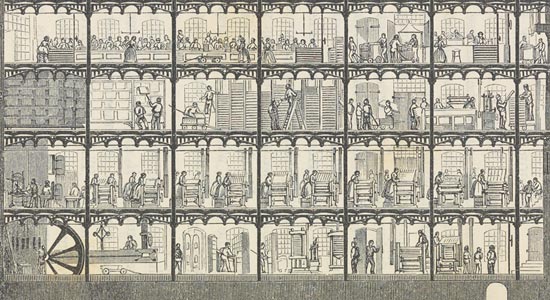

This digital publication is based on a 2014 Focus Gallery exhibit at the Bard Graduate Center that uses engravings, lithographs, daguerreotypes, stereoviews, and woodcuts, among other objects, to promote an understanding of how New York City—specifically Broadway—entered visual and material consciousness in the nineteenth century. The exhibit explores how New York’s urban manufacturers as well as residents made sense of the city and its new spatial organization through these compelling visual forms. As exhibit visitors stroll along “Broadway” and around the gallery, they will encounter the storefronts and the works of four of the best-known image producers: Mathew Brady (daguerreotypes), Edward and H. T. Anthony (stereoviews), Currier & Ives (lithographs), and Harper & Brothers (woodcuts in Harper’s Weekly). BGC students helped to develop the object list, refine the interpretation, and work on designs and content for the two digital interactive exhibits in the Gallery, and they wrote the essays that are the basis of this digital publication. The essays presented here are varied in their approach and subject, but some themes come to the fore. Celebrities such as and showman P. T. Barnum and Mathew Brady figure prominently here, as both New Yorkers and visitors flocked to their galleries. The spectacle of the streets captured our imagination, just as it did our nineteenth-century image makers and consumers. We explored how that spectacle varied significantly—from the grandeur of the bird’s-eye view from high above it all to the chaos that marked the street-level woodcuts in Harper’s Weekly. It was clear to us that seeing the city and being seen became paramount as new spaces for display, such as the New York Crystal Palace and Central Park, and new visual technologies, such as stereographs and lithographs, were adopted and commercialized. We also found that the growing disparity between the rich and the poor, the “two great classes,” could be framed in the visual terms of sunshine and shadow in order to simplify and schematize the complex development of a class society in the nineteenth-century metropolis (see Jaffee, Barnum’s American Museum).

Visions of Broadway dominated the burgeoning number of visual images of New York that poured out of commercial publishing firms and entered American homes during the nineteenth century. Broadway was the central location for most of the visual entrepreneurs of the nineteenth century, as well as the imaginative hub promoting new ways of viewing the city. This central artery ran north up the entire island and attracted business enterprises and elite residents who moved ever northward to newly developed and fashionable neighborhoods. Merchants and manufacturers separated their businesses from their residences in the early nineteenth century, choosing ever more fashionable parts of the city. Artisans and workers in those manufactories remained in the older residential neighborhoods, which grew more crowded as areas such as the Bowery and Five Points became notorious for the crime, congestion, and poverty of their inhabitants (as well as fodder for sensationalist images and texts). However, it was the rise of the middle class and the success of those clerical and commercial establishments, along with small-scale manufactories and merchants, that represented the greatest market for mass-produced goods by New York’s cultural entrepreneurs, a distinctly different situation from the luxury consumer market that continued to prevail in Europe. The growing middle-class audience in America entertained an appetite for tasteful household goods, primarily situated in the parlor, the centerpiece of the Victorian home. The parlor, with its formulaic vocabulary of upholstered furniture, its center table piled high with photographic albums, stereocards, and illustrated periodicals, along with sculpture on pedestals and colorful prints on the walls, was the key site for the formation of Victorian culture. Those prints, produced in urban venues that utilized the latest steam-powered presses for mass periodicals, or the factory-like production lines of E. and H. T. Anthony stereographs, often carried a message rooted in nostalgic views of village life that offered respite to those anxious about the growing gulf between rich and poor, city and country. Other domestic objects such as the illustrated press featured more disturbing images of urban life in the city’s tenements and poorer neighborhoods.

The tradition of visualizing cities had a long history, going as far back as ancient Rome and emerging as a popular genre in seventeenth-century Amsterdam, Paris, and London. Artists produced imaginative depictions of growing urban centers by employing panoramas and other techniques that conveyed to viewers the large-scale growth and vitality of these cities. However, New York became a major player in this story at the same time that new industrial methods made it possible to produce larger quantities of images, and the growth of the American middle class provided a new and enthusiastic market for those goods.

Artists, print publishers, and art patrons had found eighteenth-century North America to be a challenging environment; painters such as John Singleton Copley and Gilbert Stuart went to Great Britain in search of clients, and most prints were produced abroad. Domestic production and producers grew rapidly in the early nineteenth century, however, and New York began to attract artists and illustrators from Europe and the American hinterlands to take advantage of the expanding national marketplace for cultural goods. In the second quarter of the nineteenth century, the post-Erie Canal boom had firmly established New York’s commercial primacy over its seaboard rivals as it steered the nation’s trade through its slips and stores. Skilled artists and engravers left Europe for the opportunities (and the eventual problems) of finding economic success in the port cities of the northeastern United States; presses and other kinds of technical equipment followed them. New commercial and manufacturing fortunes created a bevy of wealthy collectors eager to purchase high-end engravings, and print shops and city sidewalks featured displays of prints for pedestrians. The new reproductive techniques of lithography and photography produced an ever-mounting number of images as both stand-alone objects or book illustrations. The proliferation of prints, which art historian Elliot Bostwick Davis has called “the currency of culture,” represented the leading edge of this commercial and cultural moment. New modes of perception took the form of bird’s-eye views and other panoramas, whereas street-level scenes of oyster peddlers and crowded tenements added immediacy to the popular understanding of urban life. By the 1850s, publishers offered images of the city in widely circulated illustrated newspapers that could be accessed by an interested public.

Central to this transformation was the concurrent explosion of image-making and mechanical reproduction, signs of the onset of industrialization and a mass visual culture. Not all entrepreneurs or image makers were famous or successful, of course; some struggled mightily to support themselves or distribute their prints in the tumultuous marketplace of the developing American market for cultural products. But what was not in doubt was the emergence of New York both as the center of production and distribution of this new domestic culture as its primary subject. New York as an urban space became renowned for its fashion and modernity and a magnet for tourists from all over the world.

Both the exhibition and this publication bring us closer to an understanding of New York’s role during this crucial period in its history, when the city became the primary way of viewing all cities, a model for ways in which an exploding urban scene might be understood in visual terms, through forms that gradually emerged as a conventional urban practice.